Despite the inherent chance and coincidence of Australian history, there’s a certain sense of inevitability when we trace our national narrative in hindsight. The sequence of chapters in our textbooks and syllabuses seems logical and coherent. Colonisation follows European imperialism and exploration. Suffrage follows the discovery of gold. Federation is realised after a growing national consciousness.

There’s a reason historians construct timelines: drawing a thread between moments turns the past into a sequence that forms the skeleton of our stories. We make narratives out of stuff that happened over time.

Review: Bennelong & Phillip: A History Unravelled – Kate Fullagher (Simon & Schuster)

That form of chronological sequencing isn’t innate, however. Western historical practice feels natural because it’s the way many of us have learnt history. The discipline is presented and understood “chronologically” – but its intrinsic nature belies the attention required to craft and curate a seamless logic of time.

As postcolonial scholars such as Dipesh Chakrabarty and Priya Satia have shown, the discipline of history itself has helped fashion a sense of inevitability, especially in histories of colonisation and imperial expansion. Indigenous histories and perspectives have often been relegated to the fringes of national narratives or framed in predictable tropes that saw them overwhelmed by historical “progress”.

How do we nudge at that overwhelming sense of inevitability? How might we inhabit the past and consider its chance and open-endedness, as well as its contrasting cultural readings?

Kate Fullagar’s important new work, Bennelong and Phillip: A History Unravelled, reaches into Australia’s early colonial history to tease out, quite literally, the threads of its past. In doing so, it brings a creative and original lens to a foundational relationship.

The book focuses on the curious entanglement between Arthur Phillip, the first Governor of New South Wales, and Woollarawarre Bennelong, a Wangal man born around 1764, who grew up by the Parramatta River.

Phillip was a British Royal Naval Officer with an extensive military career, including serving in the Napoleonic Wars and conflicts over Spanish colonies in South America. In 1786 he was appointed to lead the First Fleet, that famous flotilla of eleven ships filled with convicts and soldiers that established a penal colony in New South Wales in 1788.

Representing the might of a global and acquisitive Empire, Phillip has also been remembered for how he guided the colony in its early years (despite famine and unrest, as well as unimaginable isolation), along with his commitment to “establishing and maintaining friendly and peaceful relations” with Aboriginal people. His official orders to “conciliate their affections” and “live in amity and kindness with them” have framed the ways early Australian colonial histories presented Phillip as an emblem of the Enlightenment and loyal servant of the British Empire.

Bennelong was also a diplomat, a speaker of multiple languages and a curious, gregarious interlocutor. The historian Keith Vincent Smith described Bennelong’s childhood, growing up on the banks of the Parramatta River spearing snapper and cutting sheets of bark to build his own Nawi canoe. He was initiated as a teenager, where

scars were raised on his chest and arms and his upper front tooth was knocked out to show that he was a man. He could now take a wife and hunt kangaroos and dingoes.

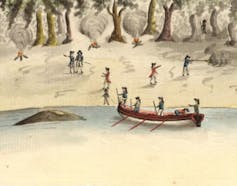

Bennelong would have been about 24 when the First Fleet arrived. He was dramatically thrust into its world when kidnapped from a harbour beach in Manly in November 1789, along with Gadigal man Colebee, in a curious attempt to build relationships between the colonists and Aboriginal clans.

Despite that violent beginning, Bennelong became a critical member of that early intercultural dialogue and was also the first Aboriginal man to visit Europe and return.

Read more: Sailors' journals shed new light on Bennelong, a man misunderstood by history

Fullagar explores how the two men’s shared history did indeed shape Australia’s, but not simply in the way foundational narratives have tended to represent them.

Bennelong and Phillip’s life stories have been told and reproduced many times before – in histories, biographies and museum exhibits. Their figures grace our currency, monuments and galleries and their names mark our maps. They are perhaps better known as tropes than actual people – representing a curious, bifurcated tale of rationality and tragedy, Enlightenment and tradition, (colonial) beginnings and (Aboriginal) endings.

Yet when Phillip was speared through the shoulder at Kay-Yee-My (Manly Cove), in retaliation for Bennelong and Colebee’s kidnapping and imprisonment, no one could have known what lay ahead. Similarly, when the colony was experiencing famine and its very existence was uncertain, or when a smallpox epidemic wiped out approximately half of the surrounding Aboriginal clans, we cannot assume people knew what would come next.

It’s difficult to understand the precariousness and contingency of this history. To do this, Fullagar reaches back in time, but does so in reverse, by inverting the narrative of their relationship. She does this to tease out the lives of the two men in their own right and on their own terms. Critically, her book also exposes the architecture historians draw on, such as using hindsight and chronology, as well as narrative, to make a story appear seamless.

Beginning at the end

Bennelong and Phillip begins at the end, with the funerals of these two men, inviting us to think about how their contrasting but intersecting lives were remembered. Then we move back in time, event by event, chapter by chapter, through the colonial period and before it, to their beginnings.

It’s an inspired approach that forces readers to wrestle with our own historical assumptions. It makes clear that for this period in Australia’s colonial past, the story certainly isn’t one of linear progress, but a messy, often shared, series of entanglements.

Given the history discipline’s own legacy in advancing settler colonialism, policing whose stories can be told, how and by whom, Fullagar is acutely aware of its limitations in retracing this period. Can a work of history, even one as original and imaginative as this one, successfully reclaim this story from the dominant narrative of early Australia, where the settler colony’s success is assumed, because we’re still living in it? It’s a question she wrestles with throughout.

Read more: Why we should remember Boorong, Bennelong's third wife, who is buried beside him

When so much Australian historiography has framed the colonial period as a set of “befores” and “afters”, “pre-history” and “history”, or “firsts” and “lasts”, this book throws the logical sequence of the colony on its head.

Fullager manages to reach back in time to disrupt and pick apart the past, without assuming she can inhabit the minds of these two men beyond her own lived experience and world view. In a memorable scene, she describes Bennelong’s visit to the London’s Parkinson Museum in 1793, where he and his Wangal Countryman Yemmerrawanne were confronted with artefacts taken from Australia, including possibly spiritually potent objects and human remains.

She cleverly reframes and describes 18th century British culture and society as an ethnographical study, suggesting what it might have looked like through Bennelong’s eyes (subtly alluding to those early colonial accounts by Watkin Tench and David Collins, which were full of cultural curiosity for the “other”). And she deftly manages and highlights the unevenness of the colonial archive, reminding us the inequity of our cultural memory doesn’t obviate the need to be attuned to a diversity of experience.

Bennelong and Phillip gives us a new, original lens onto this origin story. We see a larger, more complex picture of Phillip, for whom New South Wales was just one chapter of imperial service. And we’re offered a much richer, nuanced account of Bennelong, who Fullagar reads in context and on Country.

The book’s narrative reversal requires some skilful management to make sense. Fullagar uses helpful annotations at the beginning of each chapter, reminiscent of early colonial texts, which often included the same.

She also writes beautifully and clearly. That mastery of time and prose is essential, because this isn’t the sort of history book you can flick through on autopilot. Our narrative habit as readers to move forward through time is constantly being checked throughout. Maintaining that coherence requires work from the reader but, if this book is a little unsettling, that’s probably a good thing.

Bennelong and Phillip is a disciplinary accomplishment. Given its contribution to our national conversation, I was shocked to read reports of the Australian Catholic University’s draft plans to restructure more than 30 full-time equivalent jobs across the humanities, Fullagar’s included. In this ghastly “Hunger Games” scenario, colleagues compete for a reduced number of positions in their own area.

Given the heated debate around the Voice referendum, which demonstrated Australian history is very much still up for grabs, the sort of historical contemplation and reconfiguration Bennelong and Phillip provides is both critical and timely. I can’t think of a worse moment for a university to walk away from such important work.

Anna Clark has received funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.