Did you know the Sydney suburb Rosebery was home to the now-endangered green and golden bell frogs? That enormous cauliflowers were nourished by fresh water springs? And that dugong bones were found during excavation for the Alexandra Canal?

Research has revealed these and other water stories in a project that maps and brings to life the histories and practices of water in Green Square. For Traditional Owners, the Country now known as Green Square is nadunga gurad, sand dune Country, known for millennia for its nattai bamalmarray, freshwater wetlands and ephemeral ponds.

Green Square is Australia’s largest urban renewal project, spanning the inner eastern Sydney suburbs of Beaconsfield, Rosebery, Zetland, Alexandria and Waterloo. During the La Niña event in 2021-22, the wetlands and ephemeral ponds became visible to Green Square residents and visitors over the first year of the research project. Yet the histories of water that shaped and continue to shape Green Square remained largely invisible.

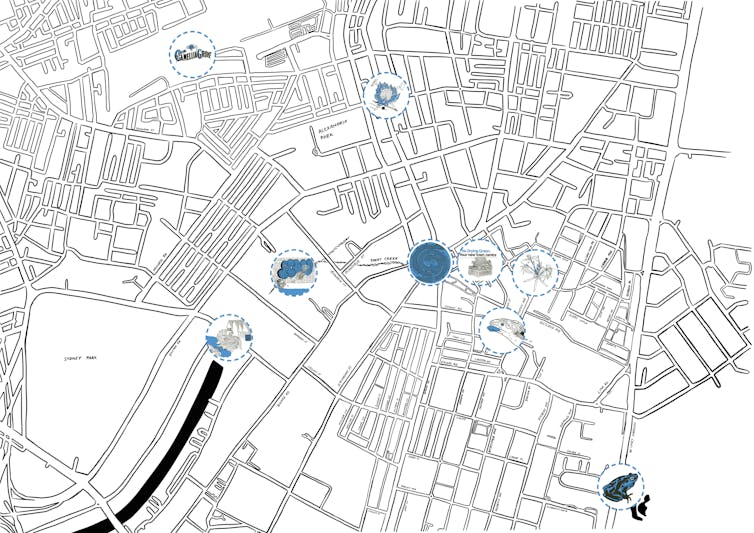

Researchers from the University of Technology Sydney brought some of these stories to the surface in a storymap. We used a software package (ESRI’s ArcGIS) to integrate maps, archival text, expert voices, photos, videos and illustrations for the Water Stories project. Telling these water stories allows us to explore the ever-changing relations between Country, development and urban imagination.

Where do these stories come from?

We went to a range of archives. Some were official, such as the State Library of NSW, the National Library Trove, the City of Sydney Archives and strategy documents, the Dharawal Dictionary, state government policy documents and federal and state parliamentary Hansards. And some were grassroots records, such as the online archive of FrogCall, the newsletter of the Frog and Tadpole Society. We also spoke to experts such as zoologists, engineers and landscape architects.

However, the largest archive we explored is Green Square itself. To understand Green Square as a living archive we identified “portals” in the landscape: visible objects that provide entry points into water stories. A pub, a plaque, a frog pond, a maintenance hole, a hoarding, a canal, a creek, a blue tongue lizard and a native flower are translated into the storymap as geolocated icons on a base map. Clicking on each of these icons transports you to a new story.

We pieced together fragments found in the archives into narratives that recover both well-known and little-known histories. These stories reveal the multiple and changing relations with water in this area.

What, for example, is the story of the pub? Perhaps you have been to the Cauliflower Hotel, one of the oldest pubs in Sydney. It was founded by George Rolfe, a well-known market gardener. Rolfe had prospered from growing a bumper crop of cauliflowers watered from springs during a drought.

Read more: Move over suburbia, Green Square offers new norm for urban living

Stories of Country and colonialism

For millennia this area was a refuge on the route between Sydney’s two harbours, Gamay (Botany Bay) and War'ran (Sydney Cove). The presence of water led settler-colonial land owners to choose this place. Thus began the colonial history of Green Square as a site of agriculture, manufacturing, industry and now residential development.

This narrative is dominant in contemporary descriptions of Green Square, but it is not the only direction these stories flow.

The endangered green and golden bell frog, we discovered, prefers to make its habitat in disturbed landscapes, such as the water pooling from sand mining, rather than in custom-made nature reserves. This may dampen enthusiasm for the small frog pond established at Kimberley Grove Reserve. But it is important to understand the complexity of how such histories intersect if we are to make better decisions about cities in the face of climate change.

Some of the other stories surfaced by the project include:

Gunyama, the name of the new aquatic centre means “stinky wind”, which could describe the smell of both ancient mangrove swamps and the noxious trades of the 1800s

a huge stormwater processing plant lies underneath Green Square. Built as part of the development, it delivers up to 320 million litres of recycled stormwater each year to new buildings and open spaces.

Read more: Not 'if', but 'when': city planners need to design for flooding. These examples show the way

On the storymap, watery words from the Dharawal Dictionary guide your interactive experience, because the premise for telling these water stories is that we understand the city as Country. Country is often misunderstood as being synonymous with land, but it comprises every aspect of the “natural” environment and ecology, including water and relationships between water and land.

We understand water is always present, even if not visible. And that care for cities means care for Country, which also means care for water.

As we collect and rearrange stories, we also create new ones. We are interested in hearing how as a resident, worker or visitor to Green Square you perceive the presence and histories of water in the neighbourhood.

By sharing your own water story you can contribute to the living archive on the Water Stories website. Simply click on the eel at the end of each story and add some text to share your story about how you experience water at Green Square.

The Water Stories exhibition, featuring illustrations by Ella Cutler printed on site at the Rizzeria, opens November 16 at 6pm.

Ilaria Vanni receives funding from The City of Sydney. She is a member of the Climate, Society and Environment Research Centre (C_SERC) and of the Creative Practice Research Group at the University of Technology Sydney.

Alexandra Crosby receives funding from The City of Sydney. She is member of The Frog and Tadpole Study Group of New South Wales (FATS)

Shannon Foster does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.