Since the first paramilitary ceasefires in 1994, the Northern Ireland peace process has addressed a series of contentious issues. Prisoners have been released, weapons decommissioned. Policing and power sharing have been discussed.

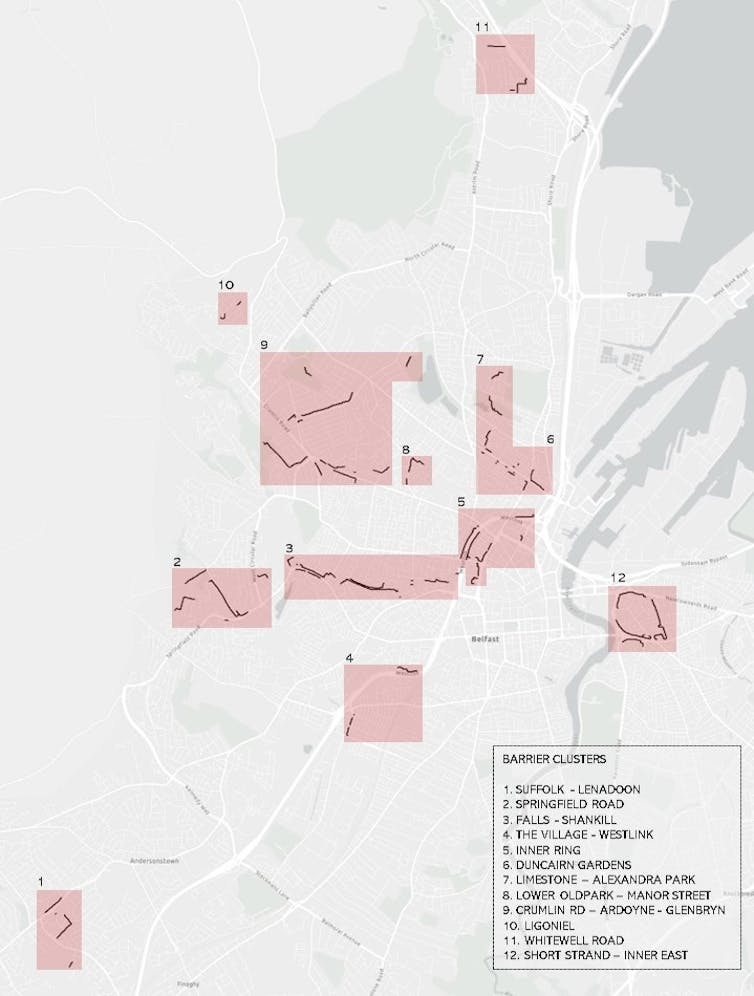

Quite how the conflict shaped the city of Belfast, though, is yet be fully contended with. The urban environment comprises 30.5 km of walls in a total of 97 different barriers and forms of defensive architecture, including walls, fences, gates and closed roads. These are primarily in the working-class communities of north, west and east Belfast. In fact, the city has more walls now than at the time of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

Paradoxically known as “peace walls”, these serve not only as physical barriers separating recognised groups with varying political, cultural or religious beliefs. They are also psychological reminders of the entrenched sectarian divisions that have long existed in the city.

Significant obstacles

In 1969, at the outset of the period of sectarian violence known as the Troubles, the British army erected makeshift barriers to limit conflict between Belfast’s nationalist communities (mainly comprising Catholic residents) and neighbouring loyalist communities (mainly comprising Protestant residents). As the hostilities unfolded, the number of peace walls increased and many became permanent fixtures. Even after the Good Friday Agreement formalised the end of the Troubles in 1998, peace walls continued to be built.

In 2013, the Northern Ireland Executive set an ambitious target to remove all peace walls by 2023. This was part of a strategy devised to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement and to demonstrate that the country has moved beyond the Troubles.

Very little has actually been achieved, however. In November 2022, Flax Street, in north Belfast, was reopened along Crumlin Road. Before that, in 2020 a corrugated metal barrier at Duncairn Gardens, that borders the New Lodge area, was replaced with a composite structure of brick topped with light metal fencing, through which residents on either side can now see.

But the government is yet to establish a clear strategy for what comes next. There are a number of reasons for this.

For a start, people have become used to the walls existing, some of them have been there many years and have become normalised. And in some areas there’s still a marked lack of trust between communities, so the walls stand for a sense of protection. Then there are the cost and logistical challenges that include potentially re-routing roads, adapting infrastructure and further modifying the urban landscape.

Finally, the political situation in Northern Ireland remains complex. Progress towards peace and reconciliation is always a slow process, and in the Northern Irish context in particular. The collapse of the devolved power-sharing executive and assembly in 2017 has made the deadline of 2023 for removing the walls appear increasingly unrealistic. Being seen to support the removal of the walls is, potentially, politically risky.

The security barriers and other forms of defensive architecture in residential areas of Belfast:

Divided public opinion

Belfast is what urban geographers term a “contested environment”. How residents in such environments cope with conflict is revealed, in part, in their everyday activities. In periods of relative calm, people in Belfast move about freely. They participate in political, social and cultural events. During marching season, however, as during summer months, the areas next to the walls become perilous.

In Belfast, gates and walls are often considered as means of solving problems but their presence divides opinion. If there is support for removing them, particularly among younger generations, a survey prepared for the UK Department of Justice in 2020 showed that 42% of people want the walls to remain in place for reasons of security and safety. Research has indeed shown that for communities living with this history of violence, the barriers provide a sense of security, so people are worried about the consequences of removing them.

The idea of implementing other changes was put to respondents, including installing CCTV cameras, improving youth programmes and promoting opportunities for the two communities to come together. While this made some people reconsider their position, 17% stated that they would not want peace walls to come, down no matter what preparations are made.

The same study found that 37% of respondents had never interacted with anyone living on the other side of the nearest peace wall. This chimes with research that has shown that the walls perpetuate division and sectarianism. They create physical barriers that restrict social interaction and reinforce negative stereotypes.

What is clear, from all studies on the subject, is that any plans to demolish the walls must be carried out in a careful and sensitive manner. They must take into account the apprehensions and concerns of the local population.

Getting rid of physical barriers is not enough. We need alternative solutions for promoting integration and getting communities to trust one another. People need to feel empowered, too, to engage with regeneration projects tackling poverty, violence and social disenfranchisement. These issues serve to divide and exclude, just as tangibly as walls do.

Teresa García Alcaraz receives funding from Spanish Ministry of Education (Margarita Salas Fellowship)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.