Happily homed in deep space, the James Webb Space Telescope has finally finished a critical stage: The telescope’s 21-foot-wide primary mirror is now fully aligned. And it has beamed down its first fully focused image to celebrate the milestone.

Although the subject of the image is a rather ordinary star called 2MASS J17554042+6551277, the image itself is anything but.

“Even though there are weeks and months ahead to really fully unleash the power of this new observatory, today we can announce that the optics will perform to specifications or even better,” gushes Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. Zurbuchen’s remarks came during a press conference on Wednesday, March 15.

“This is one of the most magnificent days in my whole career at NASA,” he adds.

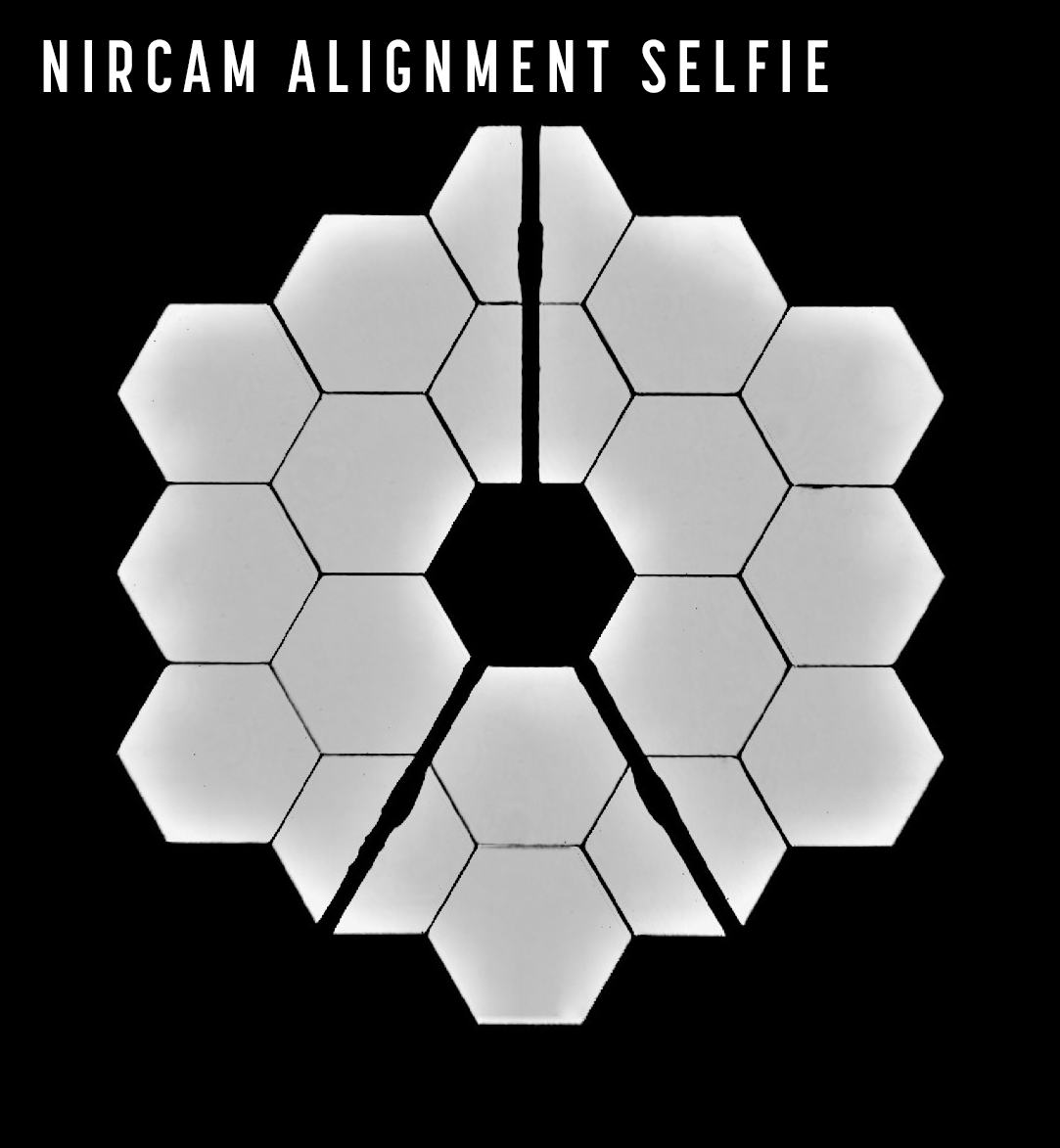

The Webb Telescope is engineered to detect light outside of the visible range — in infrared. Doing so allows it to produce images of the faintest and most distant objects in the universe. The $10 billion telescope is fitted with a 21-foot-wide, 4-inch-thick tiled mirror made up of 18 beryllium panels that are themselves coated in gold. Together, the 18 panels act as one large mirror.

NASA reveals that on March 11 those mirror segments aligned in space for the first time (almost), following a months-long process. The milestone gives hope to the mission team on the ground that Webb’s optical performance will meet their goals. This feat is only possible now because when you design a mirror this big, it has to fold up to fit in a rocket to get it into space.

Here’s what the Webb Telescope mirror looks like now in space:

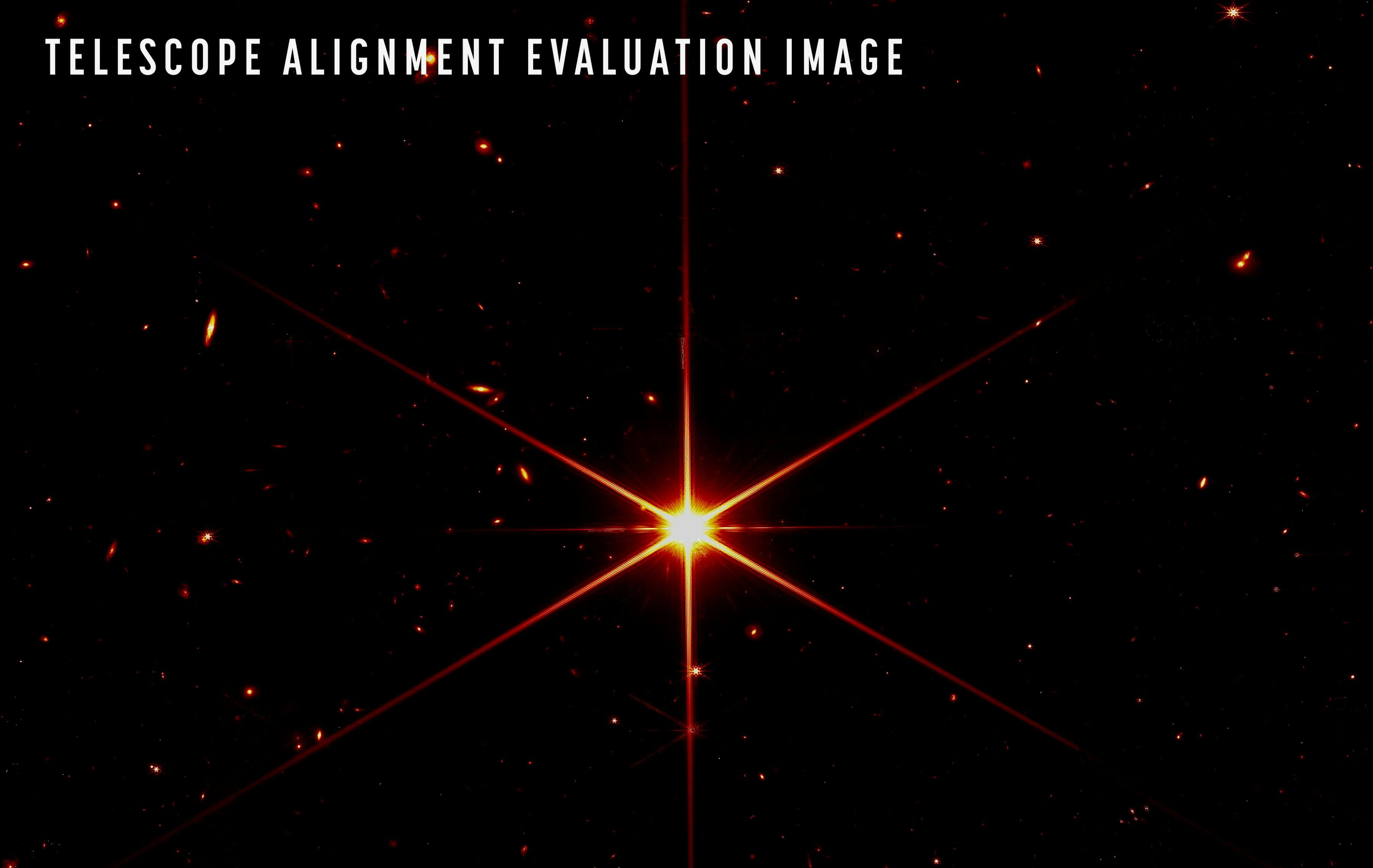

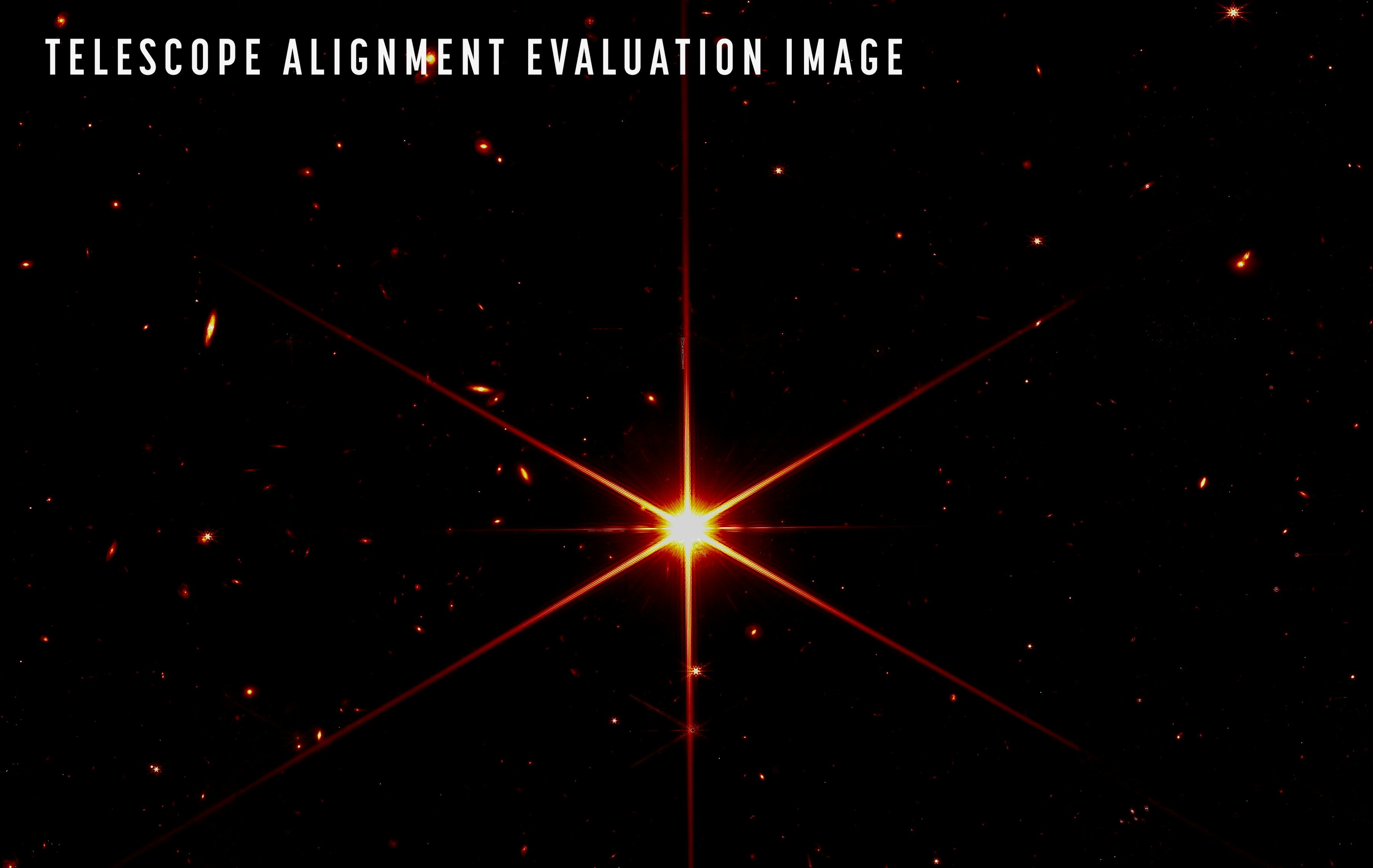

After its mirror alignment was complete, Webb snapped a stunningly sharp image of a star — 2MASS J17554042+6551277. The star is a switch in target for the Webb: Previously, it used HD 84406, a star in the Ursa Major constellation, to focus its mirrors and align them as a unit.

A red filter amps up the visual contrast:

“It’s sort of just a generic average star in our in our galaxy,” Marshall Perrin, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute, says at the press conference.

“This star is one of many stars we use throughout the commissioning process of Webb... they’re generally picked not because they’re special stars, but because they’re the right brightness in the right parts of the sky for our engineering tests.”

The Webb Telescope observes the cosmos in wavelengths beyond that which the human eye can see. The Webb’s infrared capabilities will help it stare right through opaque areas of space, capturing the universe in wavelengths that would not be possible to capture from Earth.

Webb’s optical sensitivity reveals not only the star in focus but also shows distant galaxies and other stars as faint objects in the background.

The image is also a major upgrade from Webb’s first go at photography.

Back in February, NASA revealed the very first image the telescope took of a star in the constellation Ursa Major known as HD 84406.

For its first run, Webb generated 1,560 images of the bright, isolated star. The images were then stitched together to make for one large mosaic, with each of the primary mirror’s segments captured in one frame.

What’s next for Webb

Webb is not done yet. Today, the telescope’s mirrors are still misaligned hundreds of microns or so of their desired locations. But in order to have the mirror segments all act as one, the mirrors need to be aligned within a few nanometers of one another.

“That ends up being a few 100 atomic diameters, that’s the level of precision that we need here,” Perrin says.

In order to do that, the team still has a bit of work to do.

They will begin by finding the 18 spots of light, one for each of the telescope’s mirrors, and gather those together.

“We have 18 different telescopes basically at this point,” Perrin says. “We begin by aligning them all as if they were separate telescopes.”

The full process is expected to be done by May.

Once it is up and running, the telescope is designed to look back at when the universe began, peering at ancient galaxies that formed shortly after the Big Bang. And so it is expected to deliver both aesthetic value and scientific knowledge.

“Some of what we're getting from the spectroscopy will be telling you how galaxies are rotating and how the gases of galaxies are getting blown out of them by supernova and determining what the composition of the gas and galaxies is,” Erin Wolf, a scientist on the James Webb Space Telescope at Ball Aerospace, says.

“That’s, you know, maybe a little bit geekier, but what you get out of it is really, really cool, and always gorgeous.”