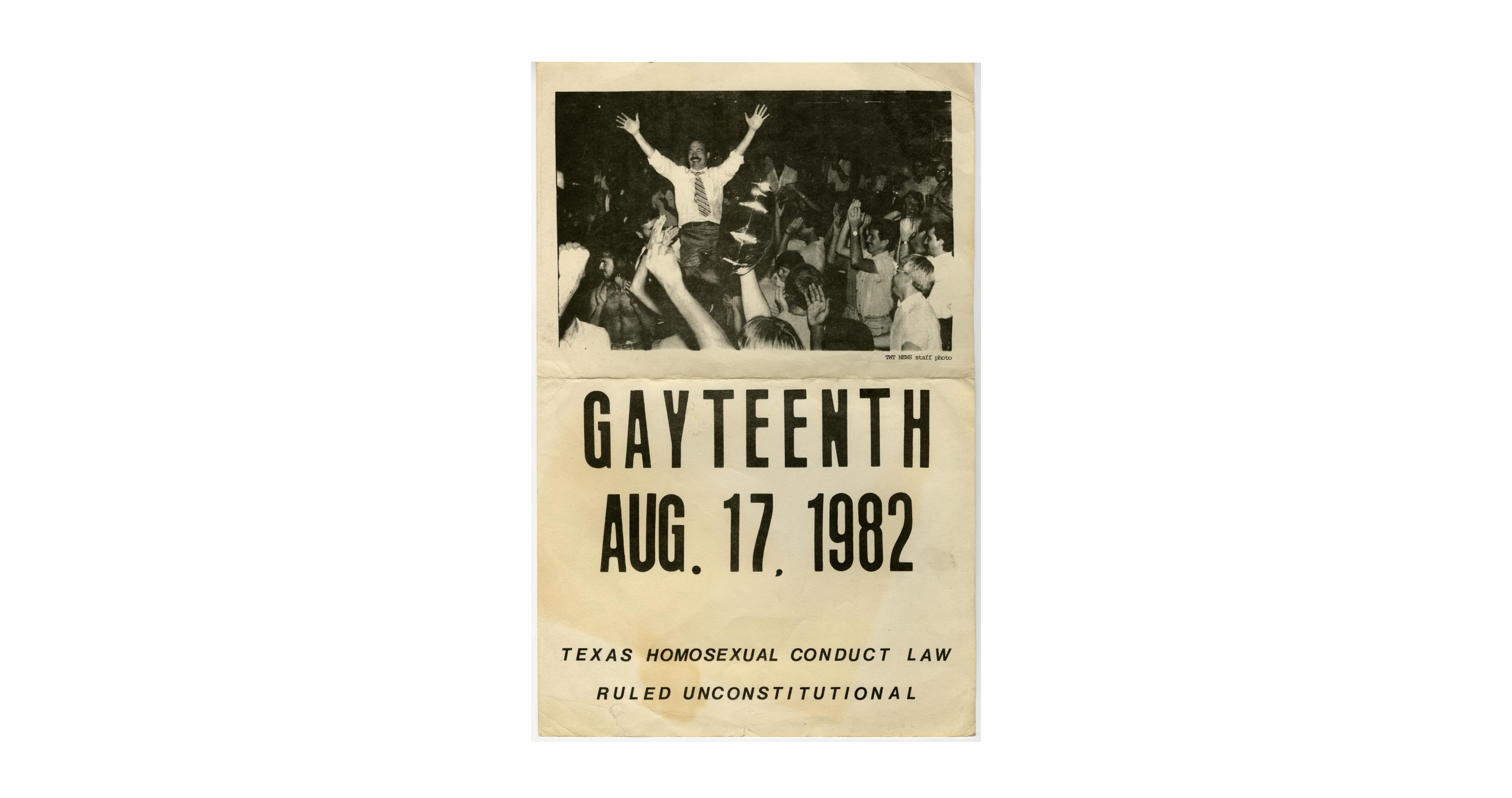

On August 17, 1982, LGBTQ+ Texans celebrated “Gayteenth,” as activists called it at the time—a reference to Juneteenth, which commemorates news of slavery’s end reaching Texas. On that day in Dallas, a district court judge ruled in favor of plaintiff Don Baker in Baker v. Wade, declaring our state’s sodomy law unconstitutional. Baker, who lost his job with the Dallas Independent School District after coming out on TV, had sued the state for violating his right to privacy and equal protection under the laws.

“I want gay people in Texas to understand that this is their victory—that they should internalize this and feel good about themselves,” declared Baker, who became a figurehead of the struggle to decriminalize queer relationships.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the decision. The Supreme Court, which had recently ruled such laws constitutional in Bowers v. Harwick, declined to hear the case. Anti-sodomy laws in Texas and elsewhere would remain on the books and in effect until Lawrence v. Texas 21 years later.

The history of Lawrence represents LGBTQ+ people’s struggle to be fully seen as human rather than as criminals and deviants, argues Wesley G. Phelps in Before Lawrence v. Texas: The Making of a Queer Social Movement, to be published this February by the University of Texas Press. Phelps, an associate professor of history at the University of North Texas, links the legal saga to the human struggle that inspired it and in the process sketches out a path for civil rights battles to come.

In the June 26, 2003, ruling, the Supreme Court of the United States overturned Texas’ anti-sodomy law, thereby striking down all similar remaining laws around the country. This massive civil rights victory freed queer people from being presumed criminals simply because of their sexual practices—a proxy for queer identity itself. Phelps places that legal decision within a web of linked historic events, from the Stonewall riots to the AIDS crisis, from Roe v. Wade to more recent victories like Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized same-sex marriage nationwide in 2015.

“While Lawrence marked a pivotal moment,” Phelps writes, “the case should be viewed as the culmination of a social and legal revolution that had been building for nearly three decades, rather than an unexpected development.”

Phelps has a gift for connecting historic turning points to familiar places within our state, including foundational gay clubs like Dallas’ Village Station and Mary’s in Houston, which became hubs of community organizing during the fight for queer equality. He invokes other figures who will be recognizable to Texas readers, including Ray Hill, the iconic gay civil rights leader who died in 2018, and former Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade of Roe v. Wade, known for supporting high-profile raids on both abortion providers and LGBTQ+ gathering places. Phelps even explores the role Texas media played in advancing or limiting progress—the Dallas Morning News editorial page, for instance, warned that overturning sodomy laws would result in “the ‘normalization’ of a practice deeply opposed by society,” while the Texas Observer (naturally) advocated for repeal.

For Phelps, the story starts in the late 1960s, when the Texas Legislature impaneled a committee to modernize the legal code. In the preceding years, a combination of the nascent LGBTQ+ rights movement and the Kinsey Reports—landmark studies of human sexuality that revealed practices like masturbation, oral and anal sex were natural and commonplace among the human species—had put pressure on legislators to reform sodomy laws.

“The persecution of homosexuals dates to the inception of the Christian hegemony … If the antiquity of the persecution partially explains the resistance to change, it also gives some indication of an enormous amount of accumulated human suffering.”—David Morris, in the Texas Observer, March 1973

Although the law was rarely enforced, anyone—even married couples—could face a felony charge with a sentence of two to 10 years in prison if caught engaging in anything other than penile-vaginal intercourse. However, many politicians and police couldn’t stomach the idea of explaining to small-town constituents why they’d legalized “gay sex.” In 1968, Bexar County District Attorney James E. Barlow warned that loosening sodomy laws would lead to “every deviate in the United States coming to Texas.”

After multiple delays (some engineered by Wade) and years of negotiations, in 1973 the Legislature adopted a reformed penal code with far worse sodomy laws. The new version spared consenting heterosexuals, married or otherwise. Same-sex partners, meanwhile, faced a class C misdemeanor with a $200 fine for engaging in oral or anal sex.

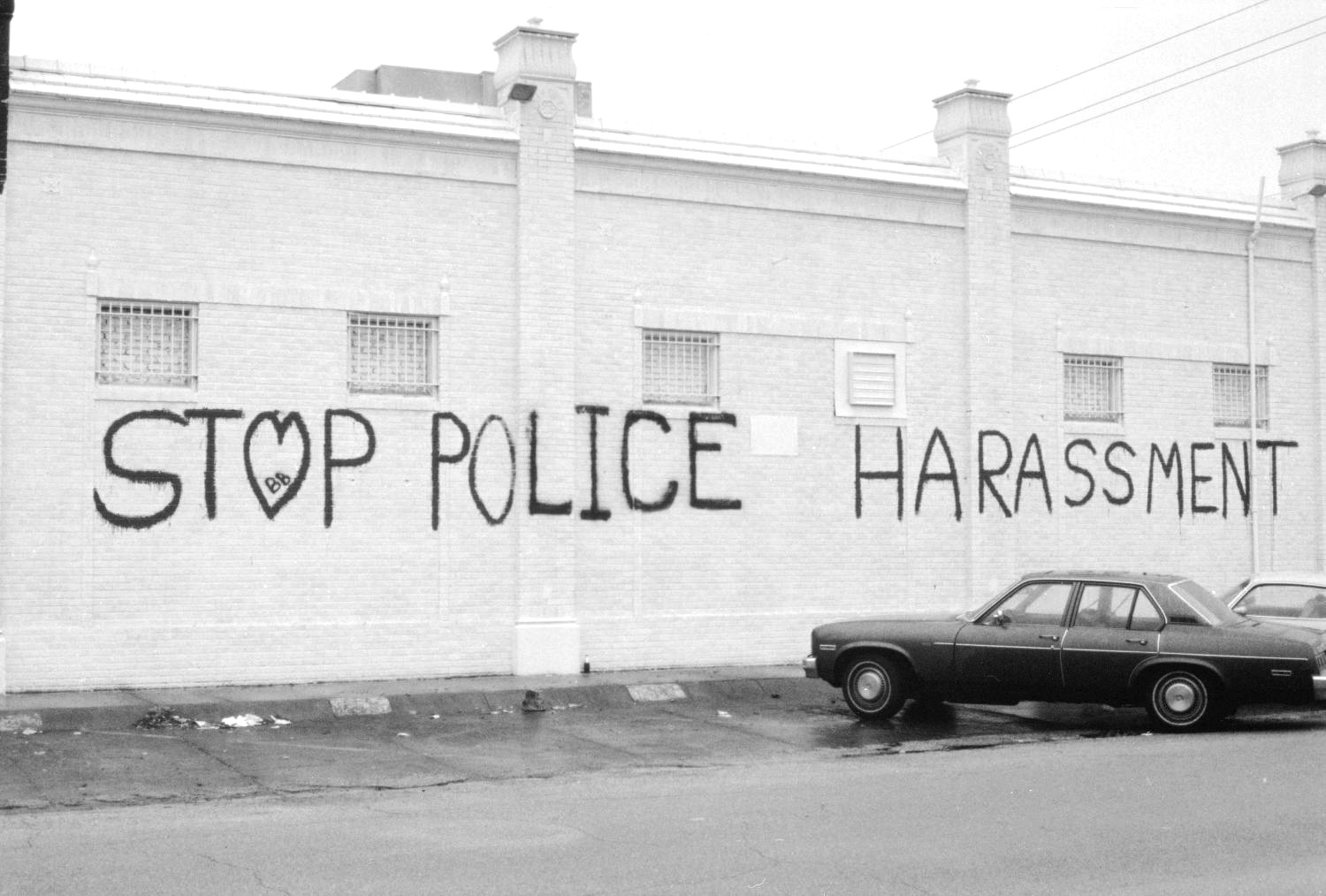

With the 1973 changes, for the first time Texas law singled out LGBTQ+ people as a distinct class deserving opprobrium. Phelps documents the far-reaching effects of this change, which included an increase in brutal police raids, gay bashing, and murders while also inspiring community defense patrols, fundraising for court cases, and other activism.

Phelps closed the book with some cautionary notes for the next generation of civil rights heroes. “The struggle for equality waged by queer Americans … would not end with a revolutionary decision by a court of law,” he wrote. Instead, it will be an ongoing struggle fought simultaneously in the courts, legislative bodies, and the streets.