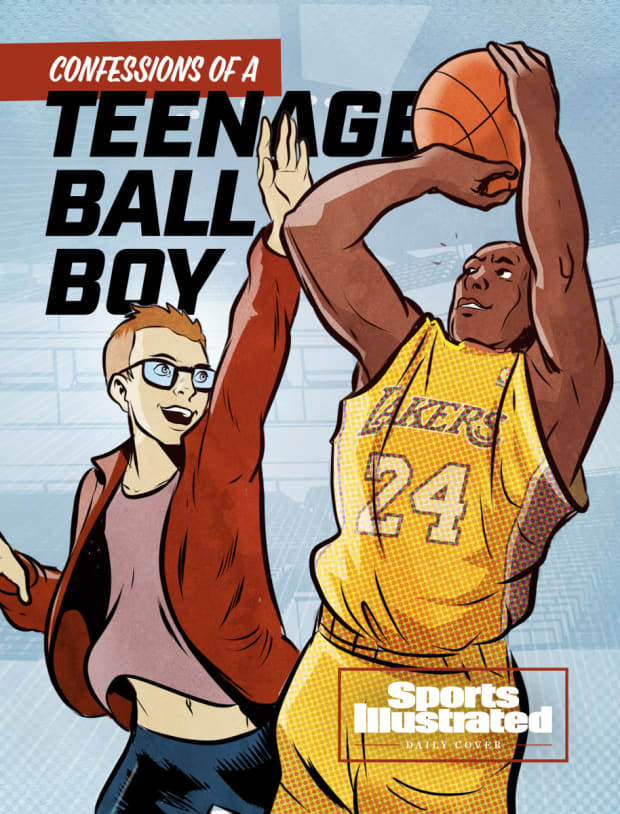

It’s been nearly 30 years since my father was asked the question, at a wedding he doesn’t really remember, from a guest he didn’t really know: Does your son like basketball? His tablemate that day—a fellow police officer, my father recalls—had some connections in the Celtics organization. If I—a skinny teenager with Coke-bottle glasses—wanted to work as a ball boy, he could get me the gig.

And so in 1995, the year the TD Garden (then called the Fleet Center) opened, I became a mop-pushing, rebound-collecting member of the Celtics’ staff. The pay was $25 per game. The stories were worth more.

In my second year I was rebounding before a game against Chicago on the Bulls’ end of the floor. Michael Jordan was among the shooters. I wore a Duke T-shirt that day—I dreamed of being the next Bobby Hurley—which Jordan, as he headed walked past me, noticed. “Duke sucks,” he said.

“You suck,” I retorted, instinctively. Bemused, Jordan motioned me over and proceeded to knock down a dozen turnaround jumpers over me. Someone snapped a photo, which sits on my desk to this day.

I’ve got a lot of those pictures. Kobe Bryant. Tracy McGrady. Ray Allen, a creature of habit, who made firing jumpers over me part of his pregame routine whenever he came to town. When I wasn’t rebounding or mopping up sweat, I was a gofer. Food, gear, whatever. In my first season guard David Wesley asked me to grab a pair of sneakers out of his car. Rushing out of the locker room, I barreled straight into Larry Bird, who was just a few years into retirement. He asked where I was going. “David Wesley needs his sneakers,” I told him.

“Tell David Wesley,” Bird said, “to get his own f---ing sneakers.”

When I told Wesley what had happened, his eyes widened: “Larry said that?” I don’t know who got Wesley’s sneakers that day. But it wasn’t me.

As I got older, I started to realize where the money was. Visiting locker room attendants—what you called yourself when you realized college women weren’t impressed with “ball boy”—were paid in cash, $50 to $100 per game from the team, plus whatever tips they squeezed out of players.

I made mental notes of player preferences. John Amaechi liked Earl Grey tea in his locker. Darrell Armstrong drank several cups of coffee before every game. Linger around Reggie Miller and Mark Jackson after games and you’d get $100 to bring a couple of small bags to the bus.

In 2001, Chicago’s Charles Oakley sent me on a McDonald’s run, with instructions to leave the bag on a specific seat on the bus. When I boarded, I walked past Jerry Krause, the Bulls’ general manager. An irritated Krause told me to take the food away. Walking back to the locker room, I saw Oakley. I explained what had happened. Grabbing the bag, Oakley opened up a folding chair a few feet from the bus. With Krause watching from the window, Oakley chowed down.

In 2002, Boston played Philadelphia in the first round of the playoffs. Before the series-deciding Game 5, Allen Iverson handed me a wad of cash with orders to buy as many Coronas as I could (plus a couple of bottles of whiskey). Late in the fourth quarter, I pushed a hand truck to the nearest liquor store. As I brought it back, a few giddy Celtics fans ripped cases off of it. Back in the building, Boston players grabbed a few more. By the time I got to the Sixers’ bus, only a few of the cases remained. “That’s all you got?” Iverson asked me. He didn’t care. He grabbed one of the bottles and boarded.

There’s more. So many more. Dale Davis betting several of us $1,000 each that we couldn’t take him in a fight. (No one took him up on it.) Getting doused with beer by Richard Jefferson after the Nets beat the Celtics in the conference finals. Darting out of the way when Milwaukee teammates Glenn Robinson and Ervin Johnson charged toward each other after a difficult loss.

I had eyes on sportswriting back then, so I leaked a few things. I found Sports Illustrated’s Ian Thomsen when I saw Larry Brown congratulating Iverson on his USA Basketball selection. I tipped The Boston Globe’s Michael Smith after Rafer Alston and Jerry Stackhouse got into it.

In the fall of 2003, I landed a job with SI as a fact-checker. My last game as a ball boy was an exhibition against Washington. Jordan was there, in his final season with the Wizards. I remember standing by his locker and thinking I’d probably never get this kind of access to him—or anyone—again.