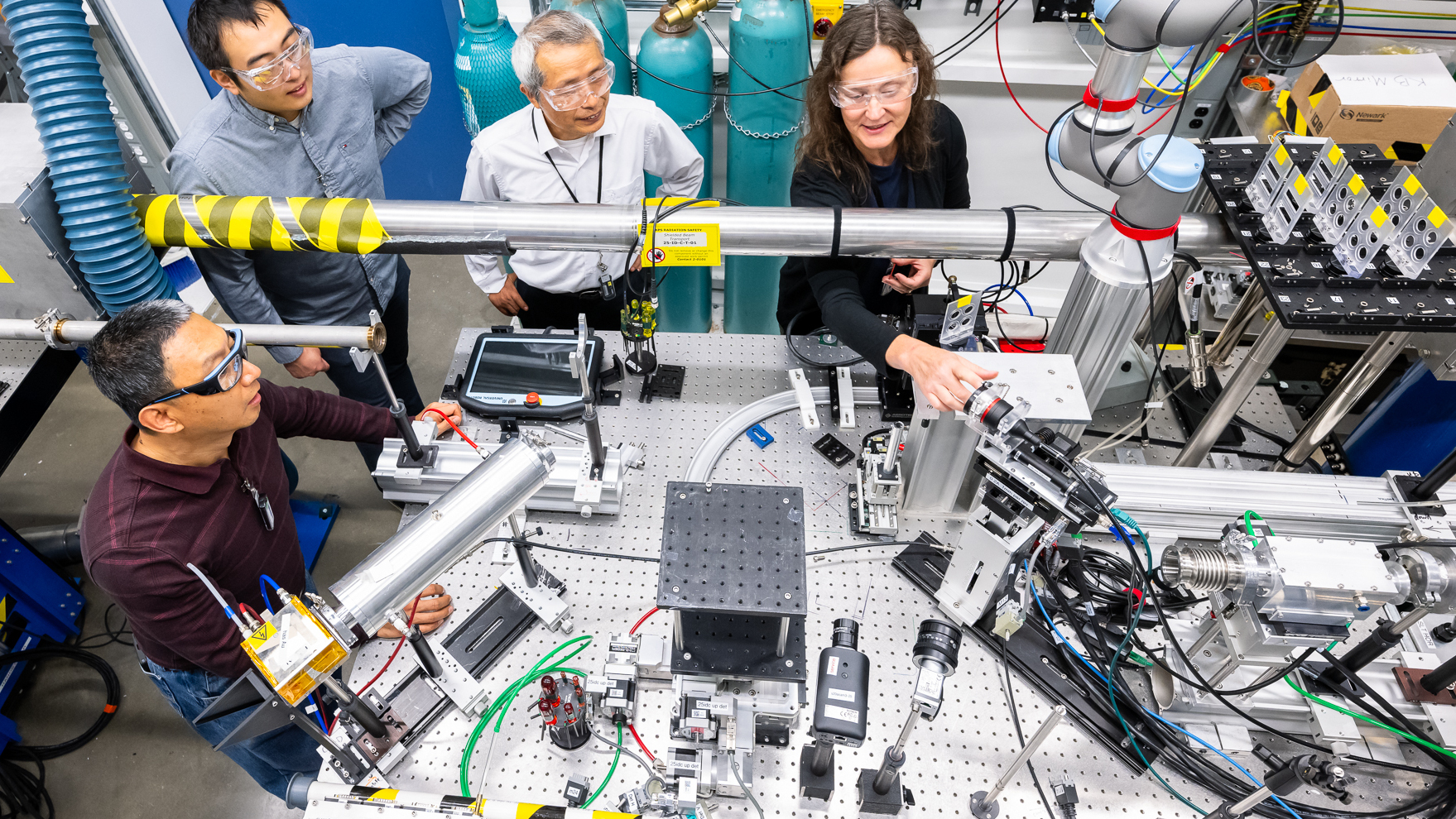

An advance in battery chemistry promises to deliver a "smaller, lighter, and cheaper battery without sacrificing end-of-life battery performance." On September 13, researchers from around the United States released a paper in collaboration with the Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory titled "Solvent-mediated oxide hydrogenation in layered cathodes", with additional comments and a summary in an official press release on the Argonne National Laboratory website. In short, the researchers used the cutting-edge X-ray technology available at Argonne National Laboratory and its Advanced Photon Source, which pairs X-ray studies and electrochemistry to allow researchers to examine their batteries at a molecular level.

But why go through all this trouble? You may or may not know this, but the rechargeable batteries available in your phones, electric vehicles and such are most likely lithium-ion batteries. Lithium-ion batteries degrade over time, getting steadily worse and worse at holding charge until they simply no longer function or can't hold a charge for a meaningful amount of time. Just because we've known how to make lithium-ion batteries for so long doesn't mean we've perfected them — advancements into "perfection" require deeper study than just being able to make a functioning item.

According to Argonne Senior Chemist Zonghai Chen, "Self-discharge is a phenomenon experienced by all rechargeable electrochemical devices. The process slowly consumes precious functional battery materials and deposits undesired side products on the surface of the battery components. This leads to continuous degradation of battery performance."

In this case, using high-end equipment allowed researchers to bridge a key missing link in existing research by getting an otherwise impossible molecular view of a lithium-ion battery in action. This allowed researchers to identify a specific process: cathode hydrogenation, which is the process of "dynamically transferring the protons and electrons from the electrolyte solvent into highly charged layered oxides in the cathode". The chemical reaction here leads to battery degradation, and while lithium-ion batteries have been known to have degradation issues for a long time, this greatly narrows down the cause.

So, what does it mean in the long term? As Zonghai Chen says, "By mitigating self-discharge, we can design a smaller, lighter, and cheaper battery without sacrificing end-of-life battery performance." This should be a pretty big step toward a future where rechargeable batteries are not awful. Here's hoping!