Russia’s first McDonald’s store in opened in 1990, just months after the fall of the Berlin Wall. It was a potent symbol that the Cold War was ending and a great ideological wound healing.

Now every McDonald’s in Russia is closed, as nations and corporations reduce, suspend or sever ties in response to the invasion of Ukraine.

The scale of economic sanctions imposed on Russia are unprecedented. It has been suggested this conflict could be remaking the world order, with Russia choosing territorial hegemony over global trade. As Craig Fuller, the chief executive of supply-chain information service Freightwaves, has put it:

If the Russia-Ukraine conflict’s international ramifications keep spreading, we face a real possibility of a bifurcating global economy, in which geopolitical alliances, energy and food flows, currency systems and trade lanes could split.

This is likely to be an exaggeration. Nonetheless shock waves are spreading through already battered supply chains. In this article I’m going to focus on three elements – energy, food and trade lanes.

Energy exports still flowing

Fears over Russia’s huge fossil fuels export being interrupted has led to global oil and gas prices spiking. Oil tanker freight rates have tripled as ship owners weigh the risk of being stuck with cargo they can’t offload.

So far, though, there has been no significant disruption to Russia’s exports. The US and UK (and Australia) are banning all imports of Russian oil, but these are not significant markets (and the UK timeline to end imports is by the end of 2022).

More important is what European Union nations do, given their high dependence on both Russian oil and gas. So far the EU has imposed financial sanctions on Russian energy producers while still buying their product.

Moving away from Russian oil is not easy. Russia has a 12% global share, and global refineries are fine-tunned to work with specific types of oil found in specific regions. Where possible, reducing production to change the oil mix that goes in takes weeks and require changes in equipment. Severing ties with Russian oil may not be an option in the short-term.

Replacing Russian gas is even more challenging. The European Union takes more than 40% of its gas imports from Russia. Pipelines like Nord Stream, connecting Russia to Germany, are unmatched. Sea transportation is limited. If oil tankers are oversized tin cans, LNG carriers are super-cooled cryogenic tanks that keep the gas liquefied at minus 160℃ degrees (-260℉). There are few players in this game, with the volume of gas transported globally about 0.1% that of oil.

Food supplies

In 2020 Russia and Ukraine accounted for 25.6% of global wheat exports (Russia 17.6%, Ukraine 8%), 23.9% of global barley exports (Russia 12.1%, Ukraine 11.8%) and 14% of global corn exports (Ukraine 13.2%, Russia 1.1%).

With higher energy prices also driving up food prices, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization has raised the alarm overfood security in Africa and the Middle East.

À lire aussi : Russia's war on Ukraine is driving up wheat prices and threatens global supplies of bread, meat and eggs

Ukraine’s exports have all but stopped. No one knows for sure how much its next harvest will be affected. Fertilisers, pesticides and fuel are scarce. Men are being summoned to join the fight. Farm supplies are redirected to besieged cities and to the army. The remaining trade routes to the west are threatened.

Russia has temporarily banned grain exports to its former Soviet Union neighbours. Along with these self-imposed restrictions, its Ministry of Industry and Trade has also “recommended” halting fertiliser exports.

Russia is the world’s biggest producer of ammonium nitrate, accounting for about a third of global exports. This will have knock-on effects for other major grain exporters such as Brazil, which imports about 85% of its fertilisers, mostly from Russia.

À lire aussi : Ukraine: how the global fertiliser shortage is going to affect food

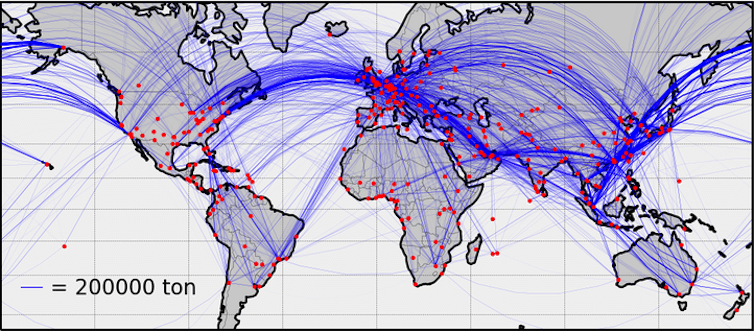

Trade lanes

The 27 nations of the European Union, the United States and Canada have closed their airspace to Russian planes. Russia in return has closed its airspace to 36 nations. This has consequences for transport costs.

Going around Russia, the largest country in the world with 11% of its land mass, is not trivial if you are flying from Asia to Europe. The cargo division of Germany’s flag carrier Lufthansa estimates doing so will reduce its airfreight capacity by about 10%. FedEx has added a war surcharge.

The war also has consequences for China’s new “Silk Road” to Europe, the world’s longest freight rail line, on which the nation has spent US$900 billion.

While China’s exports by rail are still tiny compared to shipping, they have been growing quickly. Rail routes helped alleviate the pressure on Chinese ports during the pandemic. These pressures have been building again with COVID outbreaks and hard lockdowns in port cities such as Tianjin, Shenzhen and Shanghai (the world’s largest port).

The main route from China to Europe goes through through Russia and Belarus. There is an alternative route to Turkey through Azerbaijan, Georgia and Kazakhstan but this is less established. China can also, of course, continue to use container ships. But a key geostrategic goal of its Belt and Road initiative is to secure trade routes safe from the US navy. This may dampen China’s enthusiasm for an extended conflict between Russia and the NATO nations.

The Russian invasion is a tragedy for the Ukrainian people, a challenge to European democracies, and a strong head wind to economic recovery everywhere. A potentially long conflict may be ahead of us. It is reshaping global supply chains, but for how long and by how much remains to be seen.

Flavio Macau is affiliated with the Australasian Supply Chain Institute (ASCI)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.