Drequan Barnett takes the pass behind the 3-point line. He crosses right past one defender, left on another and shoots before a third defender can reach him. The ball wobbles coming off his hand, but the 13-year-old sinks it.

“Yeah, they say he can ball,” says his smiling mother, Carlessa Ellis, watching from the sideline of the gymnasium at an East Garfield Park church.

Barnett was among about 20 boys playing basketball last week at the Night Shift, a basketball camp held twice a week at the gym, part of Mt. Vernon Baptist Church, 2622 W. Jackson Blvd.

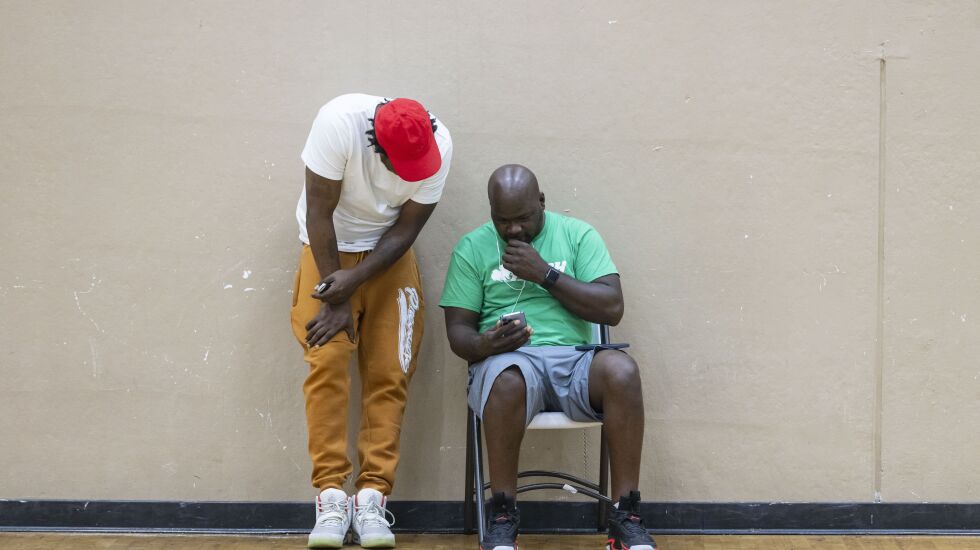

It was started by Ron “Yung” Henderson, Kevin Miller and Deonte Bell as a way to keep kids off the streets while some parents may be working — which is how it got its name.

The three grew up on the West Side and were inspired by the midnight basketball league they used to play in.

“This is a little bit of what we grew up on,” said Miller, who played at George Westinghouse College Prep.

Henderson, Bell and Miller don’t attend the church but met the pastor, Rev. Johnny L. Miller, volunteering at church events. The two Millers are not related.

“With all the shootings going on, it’s what I’d call a safe haven,” said Rev. Miller.

Four people were shot about a block away from the church on July 23, and there have been three other mass shootings in the neighborhood in the last three months. Most of those who show up — all boys tonight, but girls are welcome, too — come from Garfield Park or Lawndale, two West Side neighborhoods that are among the most dangerous in Chicago.

The problem, Henderson and the others think, is there’s nothing for kids to do.

“Kids, 13, 14, 15 years old, they have no place to go,” says Henderson, 46. “Everything shuts down at 5 o’clock. That’s why we started the Night Shift.”

The camp runs from 5:45 to 7:45 p.m. on Tuesdays and 5 to 7 p.m. on Thursdays. The partners hope to expand to five days a week and offer other activities, such as a computer class, help with homework, even drumline.

There’s no cost and no need to register. Just show up.

Inside the gym, a larger group of boys takes one half and a handful of boys takes the other. Adults give pointers on both sides and mothers Davida Wright and Monique McGhee watch with Ellis from the sidelines with their daughters.

Taking the boys to play basketball indoors was an easy sell, they say, and one which they were glad to have due to violence in the area.

“That’s why we got to keep them locked in like this,” Ellis says looking around the gym.

Among the first-timers at Tuesday’s camp was Justin Bowen, 17, Deonte Bell’s nephew.

Taking a breather after a game, he nods to the larger group of players.

“These are the ones still trying to learn to hoop,” says Bowen, who lives in Lawndale. “These ones already know to hoop,” he adds, gesturing to the group he just came from.

Tray Perkins, a special education paraprofessional at Moving Everest Charter School in Austin, gives the more advanced boys pointers as they play King of the Hill. The 41-year old likes the drill because he says it teaches critical thinking skills. The player on offense receives the ball at the top of the key and can dribble the ball only once before trying to get off a shot.

“You got to think about what you can do to get your defender off balance,” he says.

It’s tough. Deshaun Hudson returns to the larger group, where they’re playing 4-on-4, first team to 7 wins. Deshaun, 16, is the oldest of McGhee’s four boys at the camp. He considers himself more of a football player but appreciates the lessons in basketball.

“I like that we get trained to play basketball,” Deshaun says, “instead of being worried about shootings.”

The four boys, along with Barnett and another boy at the camp, Danny Irvin, usually play at Millard Park in Lawndale but feel unsafe there.

“There’s a lot of shootings going on,” says McGhee. “He was scared because of that,” she adds, referring to her youngest, Demarion McGhee, 12.

“That’s why we stay in the house and don’t go over sometimes,” Demarion says.

He sets up a few chairs to run a drill after their time in the gym is officially up. It’s a crossover drill that has him shoot from beyond the arc. One of the shortest boys on the court, he dribbles around the two chairs and hits the 3-point shot with confidence.

It’s early days for the camp, which started in July, and more kids come every week, but the founders expect it to continue to grow.

“If it’s 50 kids in here,” Miller says, “that’s 50 kids that won’t get shot.”

Michael Loria is a staff reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times via Report for America, a not-for-profit journalism program that aims to bolster the paper’s coverage of communities on the South and West sides.