The Bahama warbler, a small songbird found exclusively on Grand Bahama and Abaco, two islands in the north-east Bahama archipelago only “became” a species in 2010. But due to its limited range and increasingly fragmented habitat, the warbler was immediately treated as a species of conservation concern.

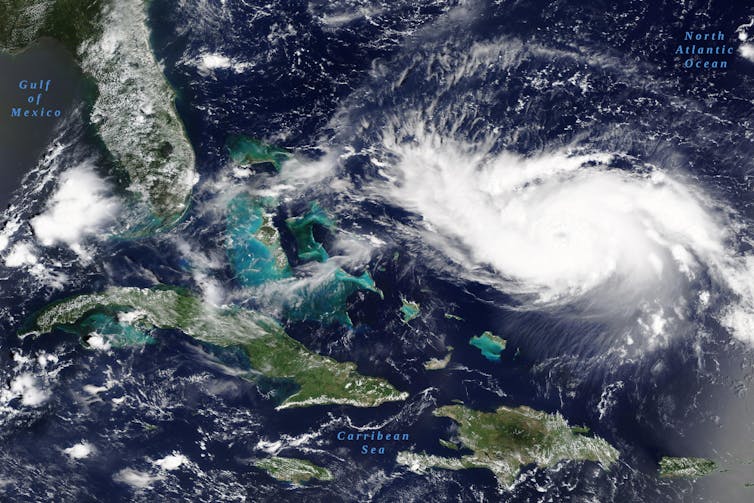

In 2016, these islands were devastated by a category five storm called Hurricane Matthew. Storms of this strength pose a serious threat to the Bahamas’s unique birdlife. So as conservation biologists, we wanted to determine how well the warbler had fared.

In 2018, our University of East Anglia Masters’ students, David Pereira and Matthew Gardner, spent three months researching birds on Grand Bahama island. They chose Grand Bahama because this island was the sole home of another newly recognised species, the Bahama nuthatch. Both species are tied closely to the native Caribbean pine forests that cover (or covered) the islands.

Matthew and David played a recording of the nuthatch’s call in order to attract and observe it. They covered all of the island this way and measured habitats everywhere to work out what particular characteristics are preferred by the two species. The fieldwork went well for the warbler, but much less so for the nuthatch.

Preferred habitat

The Lucayan estates, an area in the middle of the island where there are the most remaining pine trees, proved to be the best place for both birds. They recorded 233 warblers there and 94 further east. But at the island’s west and east extremities, where the pines were smallest and their condition poor, they found none. They only recorded a nuthatch on six separate occasions.

On analysing their data, Matthew and David found that the warbler was most likely to be encountered in areas of forest where fewer pines had lost their needles. Pine trees losing their needles is a sign of environmental stress and is induced by wind damage and saltwater penetration. The warbler also lived where thatch palms, a small tree but the largest beneath the forest canopy, were taller.

The warbler forages among pine needles, on thatch palms, and also on tree bark. So naturally, bigger pines and palms will have larger areas in which the species can forage.

Areas that had suffered a degree of burning were also favoured by the Bahama warbler. Pinewoods in the Americas tend to burn every few years. This often occurs when lightning strikes following a period of drought.

Yet these fires are usually “cool”, meaning they affect tree bark and surrounding undergrowth, but rarely the canopy. The larger pine trees and thatch palms survive these fires well.

Bark that has been damaged by fire cracks and lifts. This offers a niche habitat for insects to hide in and breed, meaning there are probably more insects per foraging patch in these areas than elsewhere on the island. This is how David explains the warbler’s use of areas where fires have created such conditions.

Species under threat

But a year after the survey, another category five storm completely obliterated Grand Bahama’s forests with winds of up to 185 mph. This storm, called Hurricane Dorian, was one of the most powerful hurricanes ever to make landfall on the Bahama’s and inflicted US$3.4 (£2.8) billion in damage.

Since the hurricane, there have been no reports of Bahama warblers or nuthatch on Grand Bahama. The Bahama nuthatch may now be extinct. But birders have more recently reported sightings of the warbler on the neighbouring island of Abaco. We predict that the warbler now only survives there.

Our research may help to conserve the remaining Bahama warbler populations on Abaco. Ensuring habitats include large old pines and tall thatch palms, preferably managed for fire, will be crucial to ensuring the species’ survival.

But climate models show that global warming is increasing hurricane frequency and raising the probability that tropical storms grow into intense, damaging hurricanes in just a few hours. Other research, carried out in 2010, indicates that tropical storms may become stronger and 2–11% more intense by 2100.

Abaco’s pine forest habitats could be affected by these more intense hurricanes in the future. Surveying the Abaco population of Bahama Warblers is now a matter of urgency to determine the species’ status on the island.

What this sad episode tells us is that conservationists will have to move warblers to other pine islands to establish reserve populations in case the next hurricane makes landfall on Abaco. This has saved other island bird species in the past.

In 2011, 59 Seychelles warblers were captured on Cousin Island and released on Frégate Island. By 2013, the population of the Seychelles warbler on Frégate had increased to 80 individuals including 38 of the original birds. However, this method is expensive as it must be determined whether the new region is a suitable host for the new species and would require significant funding and support in the Bahamas.

But time must not be wasted as the threat of extinction to the Bahama Warbler grows with each passing hurricane season. We must now try to secure the most threatened species from extinction.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.