“I’ve tried ‘em all, I really have,” Susan Sarandon’s character Annie Savoy says in the movie “Bull Durham.” But “the only church that truly feeds the soul, day in, day out, is the Church of Baseball.”

If your beliefs look anything like Annie’s, then you surely know that October is the equivalent of the Jewish High Holy Days, Christianity’s Holy Week and the Muslim month of Ramadan rolled into one, because you are eating and breathing the MLB playoffs and World Series.

If you are like the majority of Americans, though, the game is just not on your radar, unless you live in a city with a team that’s still in the running. And, as even lovers of the game must admit, baseball is certainly no longer the “national pastime.”

But there is one part of the game that still makes home-page news: the home run.

If you were aware last year that New York Yankees outfielder Aaron Judge hit 62 of them, or know about the prodigious feats of Shohei Ohtani, or you tune in to see the Home Run Derby, it’s because you know watching a baseball fly majestically in the air 400 or 500 feet and land among worshipping fans is indeed a religious experience of awe and wonder. One of those fans, in fact, will be thrilled to bring that ball home as a “relic.”

Baseball historians agree that Babe Ruth made the home run baseball’s revelatory moment. The connections between the Sultan of Swat and religion go further, though. The prodigious slugger is not just baseball’s patron saint, but its savior, returning a holy aura to the scandal-plagued game. As a scholar of religion and sports, I have argued that Ruth played another important role by making Americans more comfortable with Catholicism.

Saving a troubled sport

Before Ruth, the record for home runs belonged to Ned Williamson, who hit 27 in 1884. But the Bambino slugged 29 in 1919, 54 in 1920 and reached the Holy Grail of 60 in 1927. He finished his career with 714, breaking Roger Connor’s record of 138.

His headline-grabbing feats had an outsized impact. In 1919, baseball was reeling from the “Black Sox scandal” that destroyed “the faith of fifty million,” as F. Scott Fitzgerald put it. Several players on the Chicago White Sox were discovered to have taken money from gamblers to throw the World Series, and baseball’s reputation and popularity were in jeopardy.

Ruth – with his larger-than-life presence, rags-to-riches life story and capacity for hitting home runs galore – was baseball’s salvation. His impact on American culture can be summarized by his answer to a newspaper reporter in 1930 who questioned why Ruth thought he deserved to make more money than President Herbert Hoover. “Why not?” he said. “I had a better year than he did.”

Yet Ruth’s iconic status made life hard on those players who eventually broke his records. Roger Maris was reviled when he hit 61 home runs in 1961. Worse, when African American star Henry Aaron reached 715 career home runs in 1974, he received racially motivated death threats.

Carouser and Catholic

During Ruth’s heyday, his fame didn’t only help baseball, but religion, too. Anti-Catholic sentiment was prevalent in the United States during Ruth’s era, and his proud demonstrations of his Catholic faith helped ameliorate that prejudice.

George Herman “Babe” Ruth, Jr. was raised not by his parents, who could not handle his wild ways, but at St. Mary’s Industrial School in Baltimore, run by the lay Catholic order of St. Xavier. He was particularly influenced by Brother Matthias, who taught him to play baseball, nurtured his abilities and encouraged him to play professionally. Ruth left St. Mary’s to do so, but he retained his allegiance to the school and Catholicism throughout his life.

Everything Ruth did was reported in the newspapers, including in his own ghost-written columns. It was public knowledge that he attended mass frequently and gave generously to Catholic charities. He married in the church twice – the second time after his first, estranged wife died, reflecting Catholic teachings on divorce and remarriage.

Ruth demonstrated Catholic values in other ways. He was viewed as a patron saint of children: delighted to be surrounded by them, never refusing them autographs, and visiting them in hospitals and orphanages wherever he went. One, Johnny Sylvester, made a surprising recovery after Ruth promised him a home run and subsequently hit three in the World Series. Newspapers credited Ruth with a miracle.

Often characterized as a sinner, given his penchant for flaunting club rules and carousing off the clock, Ruth frequently and publicly repented and consulted with priests, often from St. Mary’s, who helped him acknowledge his failures and work to change his ways. He lived out the Catholic cycle of sin and repentance regularly throughout his life, expanding American society’s awareness of the Catholic value of forgiveness.

Finally, Ruth consistently stood up to team owners in support of his own and all players’ rights to fair pay, demonstrating the Catholic value of social and economic justice.

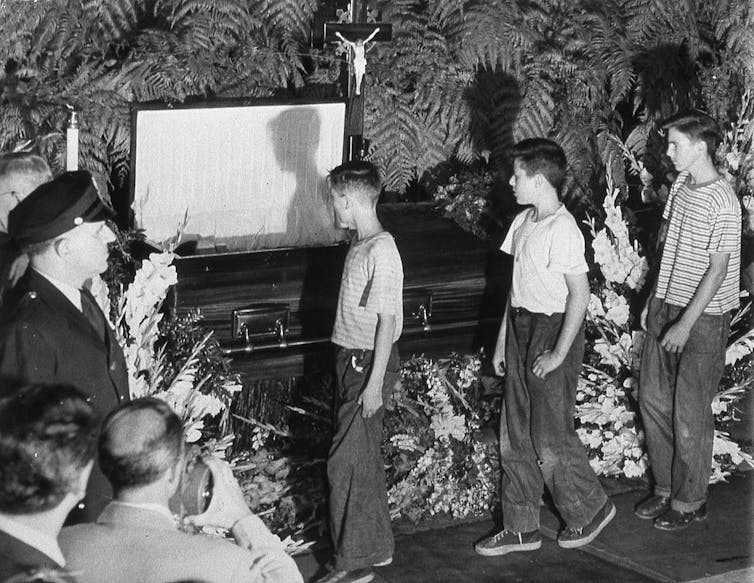

Ruth’s presence as a public Catholic continued in death. Hundreds of thousands filed past his coffin as he lay in state in Yankee Stadium, rosary beads in hand, a huge crucifix and vigil candle beside his coffin. His funeral was conducted at St. Patrick’s Cathedral by 44 priests, including New York’s Cardinal Francis Spellman. One hundred thousand people lined the route as his coffin was transported to Gate of Heaven Catholic Cemetery in Valhalla, New York.

When I was teaching a sport and society course in 2018, I came across a New York Times article about Ruth’s grave still being a pilgrimage site for Yankees fans, including an occasional nun, who hoped to help the Yankees win the World Series. Others who came to pay respects over the years were, ironically, fans of the Boston Red Sox – the Yankees’ archrival, who traded Ruth away in January 1920 – and thought his powers could reverse “the Curse of the Bambino.” And who knows, maybe they did.

His large gravestone depicts Jesus blessing a young ballplayer. For many Americans who feel something holy is happening on the ball field, Ruth was both: the miraculous ballplayer, and the godlike figure who could perform miracles.

Rebecca T. Alpert does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.