IN a study in London’s Primrose Hill, there’s a lot of what you would expect and a little of what you wouldn’t. Piles of books, a model sailboat, an eclectic collection of picture frames, and one wall that is filled with what seems to be the most well-organised mess.

This is Andrew O’Hagan’s sanctuary. And the wall of jumbled notes and papers curling at the corners? All part of his process.

“They’re kind of a distillation of years of research, boxes and boxes of journalistic literary research,” explains the author.

As I try to peek at some of the notes about his next book, he talks about the art of planning – one that is fundamental to him.

“I know there are writers who just simply sit down and write, but I’m not one of those,” he confesses. “I need to know the hinterland of each of the characters, where they’ve been. I write CVs and family trees for each of my character axes before I commit them to paper. I’m just one of those people with an apprenticeship in reporting, so, I need to find out how true things are before I can make them fiction.”

Perhaps it is because of his apprenticeship in reporting that he mostly kept quiet in the run-up to the 2014 referendum. After all, he might have thought it best to do what he was taught in a North Ayrshire primary school 40 years ago: “Watch, Listen, and Learn.”

Three years after the vote, the author gave a keynote lecture titled “Scotland Your Scotland” at the Edinburgh International Book festival. While making it clear he spoke for “no political movement”, the author explained how his view shifted post Brexit. In an opinion piece published in The Guardian, political journalist David Torrance reacted to the speech and criticised O’Hagan’s view of Scottish independence, which Torrance called “romanticised”.

Another five years have passed and the topic of Scottish independence is again front and centre as Nicola Sturgeon lays plans for another referendum. So, are O’Hagan’s political views romantic?

“Idealism is quite often mistaken for romanticisation. I haven’t been a political animal in that debate very much at all, because I think writers should go on with their writing and shouldn’t be making political pronouncements,” he says. “I made it clear to my readers that I respond to the reality of our times, and part of responding to that reality is to see what would be better and what would be the better angels of our nature in this particular circumstance.”

In this case, the better angels would lead Scotland to independence. O’Hagan now firmly believes the country would politically do better on its own.

A Scotland that is no longer dominated by the Tory voices of Westminster, whom he fervently believes don’t represent the Scottish people, is his preference.

“That’s my view. And if that amounts to romanticism in the minds of some people, then so be it,” he says. “I’m all for romance, and Scotland certainly has a lot of romance about it, but I think it’s a hard, steely realistic position.

“As a matter of fact, I think it’s a position which takes its cues from current realities in Scotland: economic realities, cultural realities, realities to do with forward thinking in relation to a whole slew of topics from public health to ways of reading, to how to run the national health service.

“I think there’s a stone cold reality when I’m talking about future freedom for Scotland. I understand all views and I’m hospitable to all views on this. I’ve never felt especially ideological on this front and I’ve never felt particularly intolerant either, but Scotland would probably do better on its own politically at this point.”

The independence debate, like so much of modern life, is one that is fired through the prism of social media and the online commentariat, some of it hastily or barely researched at all. Both professionally and personally, O’Hagan is meticulous in his research. But that doesn’t mean he sticks to specialist topics.

“You’ll find it surprising to hear me say this but the worst piece of advice I’ve ever heard is to write only about what you know,” he insists. “I’d say write about what you can know. Go out and do the research, attend the court cases, interview the individuals, get close to the social situation, examine it, learn it by heart, learn its language. Then, begin to dwell humanly within the truths that you’re finding in, and you might have a book.”

BETWEEN the known and the unknown O’Hagan found his latest novel.

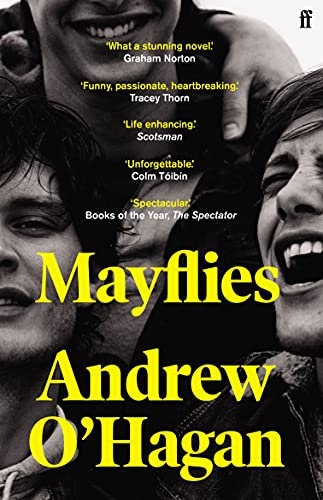

In the midst of the pandemic, the author released Mayflies, an elegy to male friendship, in which he revisited fragments of his past. The novel encapsulates the summer of 1986 and takes us where there’s music and there’s people, and they’re young and alive. From working-class Ayrshire to a festival headlined by The Smiths in Manchester, best pals James and Tully rebelliously navigate life through music and films. Everyone has a friend who defines their life. Keith Martins was O’Hagan’s.

Shortly after his close friend passed away after a battle with esophageal cancer, he wrote Mayflies. Unlike Tolstoy or George Eliot, O’Hagan didn’t wait decades to write about certain events. For him, writers must locate themselves where feels most truthful to them.

“I felt that the writing of the book was, in a sense, part of the experience of loss and recovery,” he says. “I didn’t see any benefit in waiting. In fact, I felt that some of the rawness would be useful in the construction of this book. And perhaps, I’d lose something if I waited too long.”

This rawness might be why his novel reads like poetry. There is an autobiographical element to Mayflies.

“I took from my life what I thought was right and useful for the novel, and I discarded everything else. The book was never slavishly autobiographical, it wasn’t a priority or an obligation of the novel to tell the truth as it happened in real life. In fact, it takes liberties with what happened in real life, as fiction always should. I knew that what happened in our life was significant.”

In Mayflies, O’Hagan wrote: “They say you know nothing at 18. But there are things you know at 18 that you will never know again.”

But as he sits in his study in London in his 50s, what would he say to his 18-year-old self, who was more interested in history and flowers than he was about cars and football?

“To be free sooner, and deeply free. Probably to experiment more with himself, that the world up ahead was going to be a comfortable place for him. Because that’s what you don’t know when you’re 18, you don’t know if the world up ahead is going to be hospitable to people like you,” he answers, as he takes a sip out of the same mug he used to virtually cheers us at the start of this Zoom encounter.

O’Hagan writes about male friendship like no other. In Mayflies, much like in his own life, there is no room for toxic masculinity. He argues that the categories of friendship between men are so clichéd and limiting.

“We loved each other, and love between men that isn’t sexual is something that’s very hard to describe when you come from a masculine culture,” he says. To him, Scotland and Ireland are places with a strong masculine stance where men are supposed to be men, and not to talk about their feelings nor be as affectionate as women can be.

“Well, fuck all that, I said early in my life. My friends were hugely affectionate and hugely loving.”

If there is something O’Hagan doesn’t speak so fondly of, it’s cancel culture. After writing an essay on the Grenfell Tower fire in London, O’Hagan received a lot of online backlash. He affirms nothing should interrupt patterns of resistance and individuality in human thinking.

“Freedom of speech is why I get up in the morning, it is the ink in my pen, the oxygen in my lungs,” he states quite lyrically.

O’Hagan doesn’t take for granted living in a country where people have opposite views but can share a discussion. That isn’t the case everywhere. There is no gaiety in his voice now, only gravity.

“I speak to you today in the midst of the most sad and brutal invasion and occupation of Ukraine, where a country’s individuality in its very existence is denied by the invading army, whose writers do not have freedom of speech under this imposing army.

“If you were to say the most hateful thing imaginable to me, I’m afraid, whilst not liking it, I would fight to the death for your right to say it,” he declares. “If we lose sight of that with this cancel culture, we’ve lost everything. I simply don’t trust those who wish to silence people or sack them or remove them or humiliate them or decry them for not holding their views. That’s called totalitarianism, that’s not what we do.”

SPEAKING of what he describes as a fearful culture, he argues: “Naming, shaming, and cancelling is if anything actually superficial and apolitical, it does not achieve the goals of making life better for people of colour and for women. People aren’t changing their ways, they’re simply hiding their ways, and that’s not what we want either.” But even in troubling times, there is always time for dreaming. On a lighter note, is there someone he wishes would read his work?

“I’d quite like Steven Spielberg,” laughs O’Hagan. “God, you know sometimes you imagine writers you’ve loved, reading your books and how much you’d enjoy a conversation with them.”

He mentions Robert Louis Stevenson, Henry James and James Joyce.

“I think I probably grew up in conversation with dead writers, so I’d quite like to have a real conversation with them, if you can arrange that, that would be quite nice,” he says with a playful smile.

O’Hagan works for the London Review of Books. Editor-at-large, he is a resource to the literary journal, as he makes sure that the magazine grooves with the times. Over the years, he has met quite an array of talents, some of whom he calls friends.

As he puts his journalist cap on, he wonders if I’m in Dublin and seems delighted to know instead that I’m in Limerick. He spent two nights in the Treaty City last year before lockdown and grabbed dinner with his dear friend Edna O’Brien.

“It’s got a lot of steeples; Limerick loves church steeples,” he remembers.

O’Hagan seems to be good company. Laid-back and eloquent, his demeanour is enviable during interviews. How does he remain so collected when surrounded by big talents? “When I was your age, I was quite self-conscious and probably a bit embarrassed and found it quite hard to put myself out there. But now, I’ve become so used to it,” he says.

“I interviewed Gillian Anderson the other day at a public event, and it was a breeze. We just had a wonderful time talking to each other,” he recalls. “I think it’s not just a question of confidence, but just acceptance. There’s no time to waste, there’s no time for embarrassment.”

Quite the versatile man, the author also co-owns a literary café in Primrose Hill with Sam Frears, the son of London Review of Books editor Mary-Kay Wilmers. It only takes a quick look at his Instagram to notice O’Hagan has quite the soft spot for cocktails. If he could share a few drinks with three people, dead or alive, who would be sitting at his table?

The author would love to sit down in the bar at Claridge’s and have a French Martini with Marilyn Monroe, Émile Zola, and Henry James – sounds like quite the party.

Before we log off, I ask if there is something I should know about him.

“Yes, I’m a horrible narcissist,” he says as he gets the giggles. “I’m a dreadful swimmer. If we’re ever on a life raft together, don’t let it be me who swims for help.”