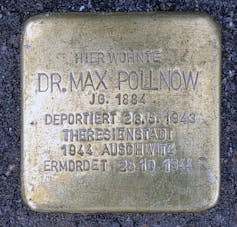

Two years ago, a small group gathered in the centre of Berlin to remember Max and Edith Pollnow, Jewish victims of Nazi persecution who “gave their lives so their son could make it to Australia”. The ceremony unveiled two Stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones”, dedicated to their memory.

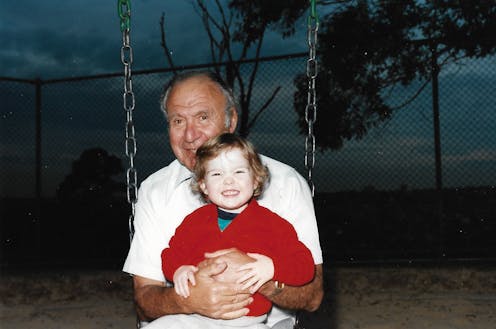

During the ceremony, a relative noted they were there because of Max and Edith’s sacrifice. The fate of their son, Hermann Pollnow (familiarly “Mutzi”; in Australia he was strongly encouraged to anglicise his name to Harry Peters), is the subject of his granddaughter Tess Scholfield-Peters’ semi-fictional book.

Dear Mutzi is part of the recently booming genre of personal attempts to reconstruct traumatic family histories through survivor memories and other documentation. It is also a way of coping with intergenerational trauma, like the recent book by another Australian author Tony Bernard.

Review: Dear Mutzi – Tess Scholfield-Peters (National Library of Australia)

One German family

The Pollnows were a middle-class family, who felt more German than Jewish. Max, a first world war veteran, worked as a medical doctor. Edith stayed at home, bedridden in later stages of what was most likely multiple sclerosis.

Similarly to many other Jewish families in Germany, they were reminded about their roots only after the rise of National Socialism. Hitler’s view of the Jews as a racial, not religious, community imposed this identity on those who had fully assimilated into the German community. Soon Max, Edith and Hermann experienced progressing antisemitic persecution.

At this point, Max and Edith decided to help Hermann escape. To increase his chances they sent him for vocational retraining to Gross Breesen. This agricultural farm in Silesia prepared young Jewish men and women for emigration. It possibly saved Hermann’s life.

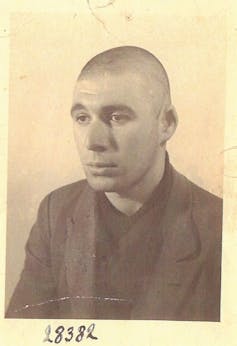

During the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938, when some 30,000 Jewish men were taken to concentration camps, all adult males from the farm were sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp. Hermann was imprisoned for almost a month and was released only because his emigration plans were lined up. A photo of him with his head shaven, taken on the day of his release from the camp, reveals the unspoken horrors he experienced.

While Hermann soon escaped from Germany, the rest of his family perished. His Oma, Ella Jacoby, was sent to the Sobibor death camp. Max and Edith were in 1943 deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto.

Edith perished two months later due to a combination of diseases, including pneumonia. In October 1944, the SS sent Max on one of the very last transports to the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was murdered only two months before the arrival of the Soviet Red Army to liberate the camp, on January 27 1945.

Hermann, now Harry, survived in South Australia before moving to Sydney, where he studied to become a medical doctor.

Troubling ethical questions

Scholfield-Peters balances on the line between fact and fiction. She reconstructs the family history for herself, in the memory of her beloved grandfather and his parents, who she never met. Sources to reconstruct Harry’s life are limited, because he only occasionally shared details about his life before and during the war.

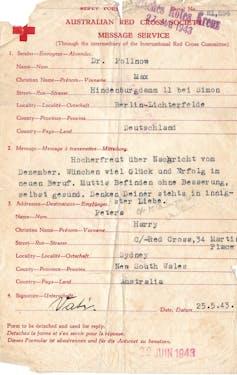

Harry left behind a briefcase with letters his parents sent to him at the time of his emigration and during his first months in Australia. But the correspondence includes only the letters Harry received, which silences the other half of the story. We will never know what Harry wrote back. After the outbreak of the war, Max, Edith and Oma only sent a few short messages, up to 25 words per message, via the Red Cross. Then they turned silent.

In 1997, Harry recorded a video testimony for the Shoah Foundation. Scholfield-Peters uses all these snippets of information to bring her great-grandparents and her grandfather, Harry, back to life. She tries to imagine how they personally experienced the episodes mentioned in the letters, depicted in photos Harry brought with him to Australia, or recollected by Harry later in his life. This is how Scholfield-Peters gets to know her relatives who perished in the Holocaust.

She struggles with the process of searching, concerned she is intruding into personal affairs that should possibly remain buried in the past. She knows what lies ahead for them, but cannot do anything to save them, or reassure Max and Edith that their son will do well in Australia.

Do we have the right to uncover long-lost traumas if those who experienced them were unwilling or unable to let us in? Are we allowed to read deeply personal letters intended only for the addressee? They reveal painful personal details from those experiencing increased humiliation, but also eternal love for their son, who they would never see again. These ethical questions trouble historians, but also descendants of Holocaust survivors.

Survivor guilt

Survivor guilt and its associated trauma are part of Holocaust history and its aftermath. Historians and psychologists have analysed how the traumatic events physically and mentally impacted those who survived. Much less is known about the experiences of prewar Jewish refugees whose loved ones, including parents, perished in the camps. Psychologists believe their feelings of having abandoned their parents and being powerless to help them triggered a deep trauma.

Scholfield-Peters adds that Harry

knew he was lucky, and he wanted to escape Germany more than anything. But his safety came at a high price, one that was never reconciled.

How did Harry cope with this trauma? With the constant reliving of the last moments he spent with his parents, his bedridden mother, or crying father at the train station in Berlin?

He knew his parents sacrificed everything for him. Even in the last message sent from Theresienstadt to Berlin, in July 1944, Max mentioned Harry’s approaching birthday and that he “would like to write to him”. Harry could read the card only after the war, when his father was dead.

A lot of the trauma and pain remained buried for decades. Harry suffered from nightmares and lived his last years surrounded by photos of those he lost. He worked exceptionally hard his whole life, retiring at the age of 92, as if trying to repay his parents for the sacrifice they made.

In the last letters he received, his father reprimanded him for complaining about the harsh conditions Harry experienced in Kuitpo Colony, a forest farm in South Australia. He said Harry should be grateful for the opportunity to escape Germany.

When Harry’s medical condition deteriorated and his dementia progressed, he often reverted to his native German. In the hospital, he kept asking for his Mutti and at nights wandered through hospital corridors looking for his family.

But the book is also about intergenerational trauma, a topic that has been extensively analysed by scholars. Not only the second generation, the children of Holocaust survivors, but also the third generation, such as Scholfield-Peters, cope with the trauma of survival.

It is possible the book is part of the healing process, trying to get to know close family members who were lost in the past. This can also be said about the laying of the Stolpersteine in Berlin, characterised in the book as Max’s and Edith’s funeral. Their remains were scattered in the River Elbe and the plains of southern Poland 80 years ago.

A long shadow, even in Australia

Scholfield-Peters brings us another piece in the mosaic of stories that remind us about the global history of the Holocaust. The story of the Nazi genocide is not only about the events in Europe, where the actual persecution and killing took place. Personal histories of Jewish refugees, who escaped persecution but whose loved ones were not so lucky, directly connect Australia to the European events.

The personal trauma that often remained unrecognised during their lives impacted survivors’ efforts to start a new life on the other side of the globe.

Bernard Marin’s book raised this issue of personal and intergenerational trauma in Australia a few years ago. Marin’s father escaped from Poland a few years before the war, but his whole family perished in the Holocaust. Although he rebuilt his life in Australia, got married and had children, he never recovered. The rest of his life, like “Mutzi’s”, was in the long shadow of the personal trauma caused by the feeling he had abandoned his loved ones.

Jan Lanicek receives funding from the Australian Research Council. He is the Co-President of the Australian Association for Jewish Studies.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.