In the Canadian parliament last year, an outcry erupted after 98-year-old Ukrainian-Canadian Yaroslav Hunka was presented to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky as a hero of the second world war.

It turned out Hunka had fought against the Allies as a voluntary member of the Nazi German Waffen-SS Galizien division. The incident was deeply embarrassing for Canada; Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was forced to publicly apologise.

The incident also highlighted the ignorance of many Canadians when it comes to world history, as well as the makeup of their own post-war immigration schemes.

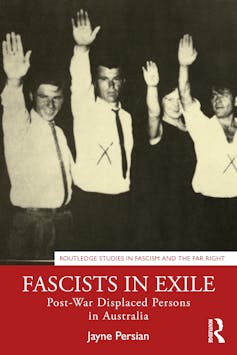

As I discuss in my new book, Fascists in Exile, Canada isn’t the only country where former Nazis fled after the second world war. And in many of these countries, families continue to grapple with the legacies of this turbulent time in history.

In Australia, for instance, when a Lithuanian immigrant named Bronius “Bob” Šredersas died in 1982, he bequeathed a significant art collection to the city of Wollongong. Last year, however, his secret history was revealed: he was found to be a member of Nazi intelligence in occupied Lithuania during the second world war. He was almost certainly involved in the persecution and murders of Jews.

In response to a report by Professor Konrad Kwiet of the Sydney Jewish Museum, the Wollongong City Council removed a plaque acknowledging the donation and updated its website with the new information about Šredersas’ past.

These may seem to be isolated, rare cases. They are not.

Denial, then investigations

Around one million Central and Eastern European “displaced persons” were resettled by the United Nations after the second world war in countries such as Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States. This group included soldiers who had fought in German military units, as well as civilian collaborators. The Nazi-led Holocaust had relied on their firepower and administrative skills.

Many of these people should have been charged with war crimes. But their resettlement in any country that would take them was a matter of political expediency in the fraught post-war and early Cold War period.

Some 170,000 displaced persons were resettled in Australia between 1947 and 1952. Jewish groups immediately protested that this group included Nazi collaborators. The then immigration minister, Arthur Calwell, dismissed their claims as a “farrago of nonsense”.

The migrants were used as labourers under a two-year indentured labour scheme and transformed into what the government called “New Australians”.

Australia received at least eight extradition requests between 1950 and the mid-1960s for individuals suspected of WWII-era crimes from Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. These were all refused with the justification that the judicial systems could not be trusted.

In 1961, the then attorney-general, Garfield Barwick, publicly stated he was “closing the chapter” on allegations of war crimes stemming from the second world war. As a result, there would be no further official discussions about any alleged perpetrators residing in Australia.

Decades later, though, all four of these main resettlement countries begin judicial proceedings against the same alleged war criminals they had ignored for so long.

Read more: The long, dark history of antisemitism in Australia

Scholars have attributed this change to numerous factors, including the trial of former Nazi leader Adolf Eichmann in 1961 and the publication of Raul Hilberg’s comprehensive history of the Holocaust, as well as more generally to the cultural shift of the 1960s and generational change.

A wide-ranging Australian investigation, established by the Hawke government, was later carried out between 1987 and 1992. Among the immigrants who were investigated were 238 Lithuanians, 111 Latvians, 84 Ukrainians, 45 Hungarians and 44 Croatians.

Allegations against 27 men were found to be substantiated, but only three were formally charged: Ukrainians Mikolay Berezowsky, Heinrich Wagner and Ivan Polyukhovich. None was convicted.

Family histories unearthed

This was not the end of the story, though.

Many alleged perpetrators of crimes never appeared on any official, or unofficial, list, either before or after the Australian investigation. But stories about individuals have come out in other ways.

My own research, for example, has resulted in the compiling of hundreds of such names by painstakingly piecing together various archival fragments.

For example, a colleague and I were alerted to some suspicious phrasing when the family of Hungarian migrant Ferenc Molnar, now deceased, placed a commemorative biography on the website Immigration Place Australia. This biography noted Molnar’s authorship of “a small book about the Holocaust”. It turned out the “small book” was a strident denial of the Holocaust, titled The Big Lie: Six Million Murdered Jews. Molnar himself had claimed to have visited the Dachau concentration camp during the war.

The SBS television show Every Family Has a Secret has been approached by at least four people who have suspected a deceased family member was a Holocaust perpetrator or collaborator. The show investigated these allegations, using overseas archival researchers. All four suspects were shown to have been allegedly complicit in crimes.

Angela Hamilton, for example, suspected her deceased Romanian father, Pál Roszy, had been “helping the Nazis” because he was a violent man and rabid anti-Semite. In fact, he had been convicted in absentia in post-war Romania of killing 31 elderly Jews.

While some families have always either known or suspected the truth, others have been shocked to find a loved one’s name in the files of the 1987-1992 Special Investigations Unit.

My husband’s now-deceased grandfather’s name appears in the files due to an anonymous allegation submitted after a public appeal for information. While the allegation was vague and unlikely, it was not impossible a 19-year-old Ukrainian nationalist could have participated in the wave of anti-Jewish violence that claimed the lives of some 10,000 Jews in western Ukraine in 1941.

Australian families will continue to reckon with stories like these, perhaps for many years to come. And more than 70 years after the first displaced persons arrived from Europe and 30 years after the Australian war crimes investigations, the Australian public is perhaps finally willing to accept that, just as Holocaust survivors resettled in Australia, so did the alleged perpetrators of atrocities.

Dr Jayne Persian receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.