Few Adelaideans remember a time before the Adelaide Festival. Formed in 1960 as a civic enterprise and financed against loss by prominent Adelaide businessmen, the festival today remains arguably the most robust international arts festival in our region.

For me, the Adelaide Festival is where I overcame my Melburnian fear of Adelaide as Australia’s serial murderer capital and the uptight “City of Churches”.

When I became South Australian, I saw how signature international festival productions had left a lasting imprint here. Many remembered freezing in an Adelaide Hills rock quarry to witness the nine-hour epic staging of The Mahabharata by Peter Brook at the 1988 festival.

And when Pina Bausch’s Nelken (Carnations) came to the 2016 festival, the lobby post-show was abuzz with people recalling the 1982 festival performance by her legendary Wuppertal Dance Theatre.

For artists and educators, encountering such works can alter the trajectory of our lives. For audiences, they can open doors of perception and create deeply embodied memories that never leave us. This is no small thing.

Local creations

The 2023 festival is curated by Neil Armfield and Rachel Healy, who stepped down as co-artistic directors in mid-2022.

Given the scale of the programming and because its core identity remains associated with theatre, dance and opera, I endeavoured to witness everything on that side of the program.

One of Armfield and Healy’s many accomplishments during their tenure was increasing the percentage of local and Australian work. Given the long history of high-quality, innovative and relevant work generated by Adelaide-based theatre for youth companies, it was heartening to see world premieres from Windmill Theatre Company/Sandpit and Slingsby in the program.

Hans and Gret brought together playwright Lally Katz, Windmill’s theatre team and the technology and experience design makers at Sandpit.

Their contemporary, highly interactive adaptation placed Hansel and Gretel in a suburban Australian gated community. Clever and engaging, it was full of unexpected surprises.

This show, and Slingsby’s The River That Ran Uphill, with its hand-made aesthetic and compelling storytelling, are equal to the best of theatre for youth anywhere.

For the Sydney Theatre Company’s production of The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, adapted and directed by Kip Williams, a team of black-clad techies and camera operators projected the comings and goings of the play’s two actors, Matthew Backer and Ewen Leslie, in a seamless combination of live theatre and cinema.

With screens behind and above the onstage action, and long narrative passages delivered breathlessly and without a pause, I found it all quite exhausting.

For my money, the outstanding Australian work in this year’s festival was Marrugeku’s production of Jurrungu Ngan-ga [Straight Talk] at the Dunstan Playhouse, conceived by Dalisa Pigram and Rachael Swain with Patrick Dodson.

State-sanctioned Indigenous and refugee incarceration was the focus of this visceral and captivating work. Eight performers, distinctive in individual presentation and styles of movement, invoked the tedium and boredom of incarceration as well as brief moments of hope and dreams of flight.

The work’s brutal honesty, enhanced by staging and lighting that suggested confinement and surveillance, was punctuated by moments of joy, humour and collective solidarity, confidently taking the audience through difficult terrain.

Read more: 'We are a nation of jailers': Jurrungu Ngan-ga is a whirlwind of bodily resistance

International offerings

This year’s high-culture, big-ticket international item was Verdi’s Messa de Requiem. The epic music and dance production featured 36 dancers from Ballet Zürich, the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, a choral ensemble of 80 and four soloists.

Choreographed by Christian Spuck with Johannes Fritzsch conducting, classical ballet was paired with Verdi’s stirring and emotional oratorio, a reflection on life, death and eternal judgement.

Although the dynamic onstage chorus contributed greatly to the overall visual spectacle, I was not convinced that the relatively conventional, classical boy/girl dyad of classical ballet was best suited for such a dynamic and dramatic musical score.

Given the political and military conflicts that continue to shake our world, not surprisingly two international works were staged by groups comprised largely of displaced persons and exiles.

Remote Theatre Project presented Grey Rock, written and directed by Palestinian playwright Amir Nizar Zuabi. A bereaved husband and former TV repair man living with his daughter in the occupied West Bank sets out to create a rocket capable of landing on the Moon.

Far from being fantasy, the work offers an unblinkered exploration of the psychological toll confinement inflicts on individuals and communities.

More harrowing in content and manner of presentation was Dogs of Europe, presented by the Belarus Free Theatre, a company of political exiles living in the United Kingdom. In their adaptation of Belarusian exile Alhierd Bacharevič’s 2017 novel, Russia has become an anti-democratic superstate, brutally ruling over eastern Europe behind a new Iron Curtain.

There was wild, anarchic energy in this youthful cast, with much played big and to excess. The show offered chilling insights into what a world without poetry or poets might look like, one in which people “are only interested in pictures” and “have stopped talking to one another”.

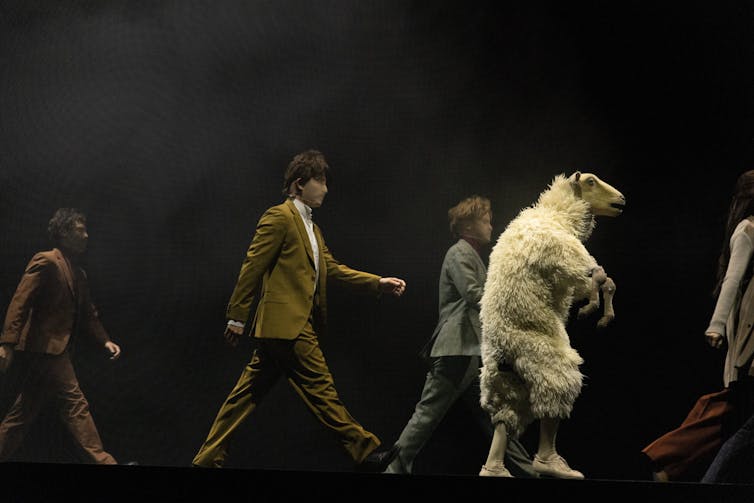

The acclaimed Belgian theatre collective FC Bergman staged perhaps the festival’s most perplexing work. The Sheep Song sets out a parable in which a lone sheep separates from his flock and seeks to become human — something he can never fully achieve.

This is a strange, cruel and melancholic world, in which the unexpected becomes continually expected, and where ultimately the surreal and the “normal” coexist.

A Little Life, presented by International Theatre Amsterdam, was the most challenging work presented this year. Directed by Ivo van Hove, known for his Roman Tragedies at the 2014 festival, the play was based on Hanya Yanagihara’s critically acclaimed novel.

The play begins with a group of young men in a New York City loft bantering playfully and with ease. Although the actors speak in Dutch, they convey a comfortable intimacy. From the start, it’s clear one of them has a terrible secret.

Containing every possible trigger warning, the work deals with extreme trauma, including horrendous accounts of sexual and physical abuse and realistically staged acts of self-harm. The play unfolds like Greek tragedy, with recollecting past trauma not leading to healing but instead to more pain.

Yet this is ultimately a play about love, and how love is not always enough to tether the people we love to this life.

Read more: Review: A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

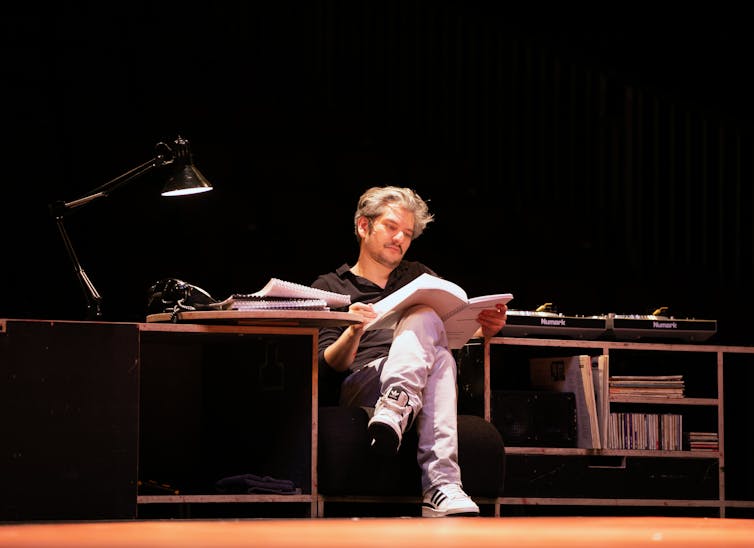

On a lighter note, but no less rigorous in presentation, was Revisor, created by Crystal Pite and Jonathon Young for Kidd Pivot, the same core creative team that brought the sensational and searing Betroffenheit to the 2017 festival.

In equal measure thrilling, astonishing and bewitching, this dance theatre piece adapts Nikolai Gogol’s 19th-century play The Government Inspector.

When a low-level functionary shows up at a government department in a provincial town and is mistaken for an undercover operative, local powerbrokers seek his attention and favour. Mayhem ensues as they offer him fistfuls of money while urging him to overlook reports of “mass graves” or “missing dissidents”.

Read more: Betroffenheit, when the mind and body get stuck

Ingeniously, all character voices are voiced over. This frees up the dancers to totally embody the words as all energy goes into the physical expression of those words, generating a performance style characterised by estrangement that is oddly very Gogol-like.

This is a sensational production, an example of a superbly successful collaboration where the artistic whole exceeds the sum of its parts.

Understanding the world

Looking at festivals in other capital cities, even before COVID hit, The Melbourne International Arts Festival was to be replaced with Rising, a lively and edgy cross between Hobart’s funky Dark Mofo Festival and Paris’ Nuit Blanche White Night.

Sydney’s festival is now a delightful celebration of Sydney in summer. Brisbane’s excellent festival lacks a significant strand of international programming, while Perth Festival, the nation’s oldest, has increasingly focused on film and the visual arts.

In the larger national festival ecosystem, the Adelaide Festival retains an unbroken line back to the original intent of those who set it up more than 60 years ago: to bring audiences a curated program of exciting new works we would otherwise never be able to see.

We see the world differently through such encounters.

William Peterson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.