While some critics have spent the last decade arguing about whether or not video games should be considered “art,” NYC’s Museum of Modern Art has been amassing a spectacular collection.

Individual titles from MoMA’s 36-game collection have, at times, been displayed for consumption at the museum, but its latest exhibition, entitled Never Alone: Video Games and Other Interactive Design, gives them an unprecedented amount of space and analysis. Never Alone is about as interactive as a MoMA exhibition could be, with 10 playable games ranging from Pac-Man to Minecraft. All 36 titles are represented through video alongside other curated displays.

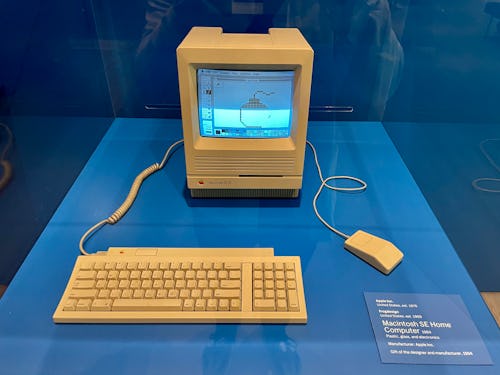

Visiting the exhibition — which is, by the way, free and open to the public — is a quick exercise in synthesis. Senior curator Paola Antonelli and collection specialist Paul Galloway have, along with a small team, divided Never Alone into three pillars: The Input, The Designer, and The Player. Each section contains both games and other elements of interactive design (like Susan Kare’s sketchbook containing original Mac icons). The visitor is tasked with collecting experiences (i.e., playing games) and considering how each contributes to a larger discussion of interactive design via these categories.

The full glory of MoMA’s video game collection must be imagined, here. This is just a taste, an invitation to go home and learn more.

Both Antonelli and Galloway have spent many years working on curating MoMA’s video game collection, with Never Alone the first time that collection has been given the full gallery treatment. Input talked with Antonelli and Galloway ahead of the exhibition’s opening to learn more about translating the curation process to cover video games and how gaming has changed our lives for good.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How long have you been curating Never Alone? What has that process been like?

ANTONELLI: It’s not really about curating the exhibition but rather about forming this collection; this exhibition is a display of a collection that’s been in the works for more than 10 years. When MoMA decides to begin collecting a new category of objects, it does so in a very deliberate way, we create a real case and argument for it. We started that back in 2006, believe it or not, we made the decision to collect film titles and fonts and interactive designs. MoMA has existed since 1929, and our collections document the art of a time. As time changes, our collections have to evolve with it.

GALLOWAY: We developed criteria for collecting video games that was really a kind of taxonomy for taking apart a game and looking at its constituent parts. Everything from the behavior of the player, the shaping of space, the manipulation of time — because, of course, video games are a time-based medium — and aesthetics, which is of course a very important consideration for an art museum. It helped us create a way of framing every game that’s under consideration.

Does this exhibition cover all of MoMA’s video games then?

GALLOWAY: Yes. This isn’t the first time we’re showing video games at the museum and it won’t be the last. That’s a key difference between what our project is and what has been done by other museums — and others have put together really fantastic shows. But for us, these are a recurring presence in the galleries. Sometimes it’s just one or two, but they are part of our collection, and they continue to appear on our walls.

“My idea was to avoid nostalgia... I dreamed of focusing on the behaviors between the person and the machine with no environmental interference.”

The most recent game in the collection is from 2018. Video games have already changed so much since then. Do you have any concerns that the exhibition might not be up-to-date enough?

ANTONELLI: It’s interesting. Every object that we acquire is frozen in time. So we’re not very concerned with updating them but rather in trying to represent a version that shows the full glory of a particular game. So with something like SimCity 2000 or Minecraft we decided to just show one version, for example.

And acquiring video games is so much more complex than it seems. We don’t go out and buy the game — we establish a relationship with the production company, we make sure we’ll have the right to migrate the game and emulate it ourselves — it’s a really big scaffold to create a collection of video games. So we make choices not about the latest or most popular but rather about us showing the world what we think is the greatest expression of contemporary design.

GALLOWAY: And I would emphasize that that thinking is ongoing. The most recent game is from 2018, but we’ve been thinking about that game for several years. Likewise, there are games out right now that we’re evaluating. You have to spend time with these things to really get a full understanding of them.

Were there any cases it was particularly difficult to acquire a game for the museum?

ANTONELLI: I mean, notice there are some games that are missing from the collection. Let’s put it that way. [Laughs.] Well, there’s Zork, for instance, which nobody knows who it belongs to so we can’t acquire it.

GALLOWAY: It really varies. We have titles that come from gigantic studios like Microsoft or Sony, some from small indie studios, we have some from individual designers. It’s, of course, more challenging to deal with a sprawling, corporate behemoth. I’d say for all the games in our collection, though, eventually the parties came around and it wasn’t so difficult. The only ones that were truly difficult didn’t work out in the end.

ANONELLI: Which is sad, but it’s not just this collection. We have similar cases in digital design — it’s not just like going out and buying a chair. There are issues of IP, of the end user license agreements. We had to talk some producers into changing the EULA for us.

GALLOWAY: There’s a culture clash. These are IP lawyers spend their time monetizing intellectual property. They do that in a certain way. When you’re asking them instead think of them as cultural objects, they have to reframe it both conceptually and legally.

ANTONELLI: Designers want their work to be in the museum, of course. It’s the lawyers that stop them.

“My relationship with video games is a relationship that makes me feel the pulse, the beating heart of the world.”

No consoles are shown at the gaming stations. Was that an early decision? Was the other side of that — displaying each machine — considered as well?

ANTONELLI: It was an early decision, I’ll take responsibility for it. It was discussed with the original committee of gamers, game designers, and experts, more than 10 years ago. My idea was to avoid nostalgia. You see many exhibitions of video games that are trying to rebuild an arcade — the whole culture and gestalt of an arcade. I dreamed of focusing on the behaviors between the person and the machine with no environmental interference.

I remember at the time I was afraid I would get crucified by the committee. But instead there was an understanding that if you want to see games in their natural habitat you can go to other museums or an arcade. All museums should be part of an ecosystem; you should try not to mimic what others are doing but rather complement it.

GALLOWAY: I strongly agreed at the time. I mean, I’ve been gaming since the ‘80s. I see many of these games and I’m transported to a beanbag with a two-liter bottle of Mountain Dew and a bag of Doritos in my lap. I think the style that Paola developed actually helps me see them in a much more critical manner, because you’re really focused on what your hands are doing with the joystick, you become more aware of what’s happening on screen, too. It really facilitates a critical reading of things we’re often extremely familiar with.

Has organizing and curating this project changed your relationship with video games?

GALLOWAY: Working with Paola for this long on it has made me reevaluate a lot of things I took for granted. I’ve also met all of these amazing designers and it’s really shown me how the way we use video games continues to change. I think for me it’s been looking at the history and how the way we use video games is still evolving — I find that extremely exciting.

ANTONELLI: It hasn’t really changed the way I relate to video games. For me they’re always a temptation I stay away from because otherwise I would get completely sucked in. But this work has also connected video games to the rest of the world for me. They’re the crystal-clear example of interaction design, the same type of design used for something like New York’s MetroCard machines.

Video games, to me, are a great example for distilling something that’s all around us. My relationship with video games is a relationship that makes me feel the pulse, the beating heart of the world. I love them, and I’ll keep on loving them, and I want to see where they will go.

Never Alone is available for viewing (and playing) now through July 16, 2023, at the Museum of Modern Art.