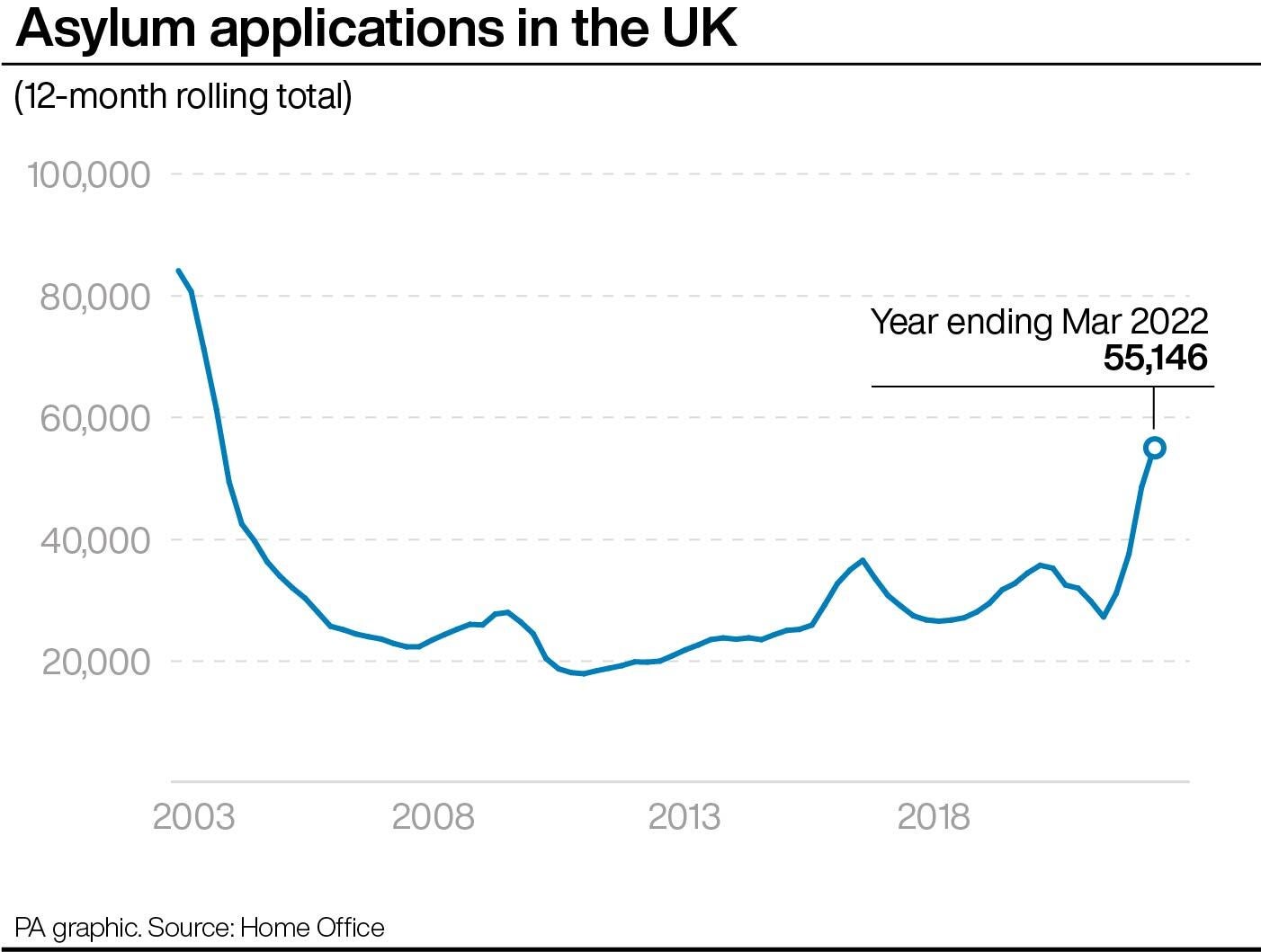

The number of asylum claims made in the UK has climbed to its highest in nearly two decades, while the backlog of cases waiting to be determined continues to soar.

There were 55,146 asylum applications in the UK in the year to March 2022 – the highest number for any 12-month period since the year to September 2003, when the total stood at 61,343.

The number of applications from lone migrant children is also at its highest level for any 12-month period since records began in 2006. Some 4,081 applications from unaccompanied asylum-seeking children (UASC) were made in the year to March 2022.

The increase in applications was “likely linked in part to the easing of global travel restrictions that were in place due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and to a sharp increase in small boat arrivals to the UK”, the Home Office report said.

At the end of March 2022, there were 109,735 people awaiting an initial decision on their case, 66% higher than the previous year when 66,185 people were waiting.

This is more than double the number in March 2020 when the coronavirus pandemic began (51,906) and is a new all-time high since current records began in June 2010.

The figures come as the Home Office announced it was setting up an action group to look at how to speed up the processing of asylum claims in a bid to increase the number of decisions made on cases on a weekly basis.

Amnesty International UK accused the Home Secretary of “disastrous leadership” over the figures, describing the Home Office as “becoming a byword for backlogs and dysfunction”.

Steve Valdez-Symonds, the charity’s refugee and migrant rights director, said: “Priti Patel’s failed asylum policies have caused huge delays in the processing of claims, and thousands of people seeking a place of safety have been left in limbo and misery.”

Enver Solomon, chief executive of the Refugee Council, said: “It is desperately worrying to see just how sharply the numbers of people waiting for a decision on their asylum application has risen over the past few years.

“This leaves thousands of vulnerable men, women and children trapped in limbo, adults banned from working, living hand to mouth on less than £6 a day, and left not knowing what their future holds. This is simply not good enough.”

He urged the Government to “create a fair, humane and orderly asylum system that speeds up decision-making”.

Of the 109,735 people waiting for an initial decision on their asylum application at the end of March this year, 14,003 (13%) were Iranian nationals, 12,740 (12%) Albanian and 12,156 (11%) Iraqi, according to analysis by the PA news agency.

Afghan nationals accounted for 5,975 of the total, or 5%.

Some 5,364 Syrians were waiting for a decision, who also comprised 5% of the total.

A Home Office spokeswoman said the department had “helped thousands of people through our generous safe and legal routes including those fleeing Putin’s war in Ukraine, refugees from Afghanistan and our BN(O) Hong Kong route.

“And as we bring the Nationality and Borders Act into practice, we are working urgently to speed up processing of claims, including via a new asylum action group.”

A total of 15,451 people were granted protection in the year to March 2022, up 79% on the previous year (8,635) but below the 20,295 in 2019.

Three-quarters (75%) of all initial decisions in the year ending March 2022 were grants, which is “substantially higher than previous years”, and the highest rate in more than 30 years, since 82% in 1990, according to the Home Office.

The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford highlighted that 76% of asylum claims among young men aged 18 to 29 were positive in the year to March.

Senior researcher Dr Peter Walsh said: “The Government has recognised three-quarters of asylum applications as valid over the last year. This is a significant shift compared to a few years ago, when the majority of asylum applications were initially refused (even if many of these were later overturned on appeal).

“We now see majorities of positive decisions across a range of groups, from young men to older women. This highlights that policies targeting asylum seekers will inevitably affect some people who would be granted refugee status if their claim was processed in the UK.”

Before Brexit, the UK was part of an EU returns deal known as the Dublin agreement. Immigration minister Tom Pursglove previously admitted there had been “difficulties securing returns” as there was not a subsequent returns agreement with the European Union in place.

The Home Office report said: “A third country refusal refers to the UK determining that it is not the country responsible for considering a person’s asylum claim, to return them to the safe third country in which the person was previously present or with which they have some other connection. The use of this decision outcome has been affected by the UK leaving the EU.”

The figures also showed 2,761 people were deported from the UK in 2021 – 62% fewer than in 2019 before the pandemic. The vast majority of enforced returns were for foreign criminals, most of which were EU nationals.