Astrud Gilberto didn’t set out to be an ambassador of bossa nova, the laid-back Brazilian musical genre with rhythms recognizable to music lovers around the world.

According to Gilberto, who died on June 5, 2023, at the age of 83, she wasn’t expecting to be on the 1964 recording of “The Girl from Ipanema” – the song for which she is best remembered.

At the time of the recording, she wasn’t even a professional singer.

But Gilberto’s breathy singing voice – almost a whisper, with no hint of a vibrato – helped catapult the song, the singer and bossa nova to the forefront of international pop music.

But while she went on to achieve global fame, back home in Brazil, Gilberto was never given the respect that I believe her talent deserved. In 1966, in the only major performance she gave in her home country, she was booed.

When bossa went big

Astrud Gilberto and “The Girl from Ipanema” marked a turning point in bossa nova.

The genre had appeared in Rio de Janeiro in 1958, when João Gilberto invented a new beat on his guitar out of the traditional samba. Compared to samba, bossa nova featured a more relaxed rhythm, with an emphasis on harmonic melodies that João Gilberto and composer Antônio Carlos Jobim had drawn from American jazz.

In 1963, American jazz saxophonist Stan Getz invited João Gilberto and Jobim to record a jazz-bossa album with him in New York.

At that time, jazz in the U.S. was waning in popularity, with other genres, such as rock ‘n’ roll, starting to attract more fans. Getz, in search of a new sound, had had huge success with his 1962 album, “Jazz Samba,” the only jazz album that had ever hit No. 1 on the Billboard pop charts. The foray in bossa nova with two established stars of the genre was going to be his next move.

By then, many American music lovers were already somewhat familiar with bossa nova. Before Getz’s “Jazz Samba,” the 1959 hit Franco-Brazilian movie “Black Orpheus,” with its theme “Manhã de Carnaval,” had introduced the genre to a global audience – the film won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival and a best foreign language Oscar in the U.S.

Jazz singer Tony Bennett was also an early champion of the genre, arriving home from a 1961 trip to Rio de Janiero with an armful of bossa records, and he may have inspired Getz to collaborate with some stars of the genre.

João Gilberto arrived to meet Getz at a Manhattan recording studio accompanied by his then-22-year-old wife, Astrud.

What happened next is contested, with Getz claiming credit for suggesting that Astrud sing two tracks: “The Girl From Ipanema” by Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes, and “Corcovado” or “Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars” by Jobim only. Astrud spoke English, along with a handful of other languages, in addition to her native Portuguese.

Astrud was, at that time, not a professional singer although she had sung in a couple of clubs in Rio de Janeiro. Nonetheless, she possessed a voice that suited the bossa style. Before bossa nova emerged, the Brazilian “cancioneiro” was dominated by an opera-like way of singing, where the singer imposed an image of grandiose figure to the audience. In the quiet and minimalist revolution of bossa nova, however, the singer’s personality is subdued; the music and the melody take center stage.

In that style, Astrud almost whispers her way through “The Girl From Ipanema” and “Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars.” Getz’s saxophone solos are similarly low-key. There is nothing flashy. It is all about the melody, the rhythm and the harmony.

And yet the restrained vocals and sax, together with the easy-flowing melody, proved a potent mix. When the track was released as a single in 1964 – with João Gilberto’s Portuguese verses cut out – it became a massive hit. Today, “The Girl from Ipanema” is the second-most-recorded pop song of all time – bested only by The Beatles’ “Yesterday.”

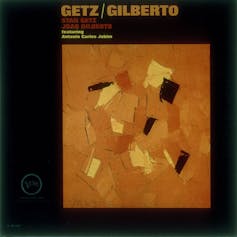

The album it appeared on, “Getz/Gilberto,” also became world famous, spawning a live follow-up, “Getz/Gilberto #2,” a year later.

Brazil turns its back

But the “Gilberto” in the album title was very much João, and not Astrud.

João Gilberto was paid US$23,000 for the “Getz/Gilberto” session. Getz himself pocketed close to a million dollars from sales. Astrud reportedly received just $120. She also didn’t make it onto the credits of the original album.

Indeed, as the song grew in popularity, Getz reportedly called Creed Taylor, head of Verve Records, to make sure Astrud would not be included in the share of the royalties.

Nonetheless, back in Brazil she was portrayed as a “lucky girl” who found overnight fame simply for being in the right place, with the right man, at the right time.

She divorced João in 1964, and the press in Brazil blamed her for the collapse of the marriage, amid rumors of an affair with Getz. No doubt, the misogyny of Brazilian culture at the time played a role. Her son, Marcelo, later recalled in an interview that “Brazil turned its back” on his mother, adding that “She achieved fame abroad at a time when this was considered treasonous by the press.”

Astrud Gilberto went on to have a successful career, releasing 17 original albums from 1964 to 2002 and collaborating with figures such as Quincy Jones, Chet Baker, Stanley Turrentine and George Michael.

Despite her success, she was never accepted as a star back in her native Brazil. In this, she was not alone: The country rarely embraces Brazilians who rise to stardom while living abroad, particularly in the U.S. Before Gilberto, singer Carmen Miranda got the same cold shoulder. And Brazilians similarly shunned bossa nova legend Sérgio Mendes, who rose to fame in the late 1960s.

Astrud Gilberto ultimately only performed once in her native country after finding fame and emigrating to the United States in the mid-1960s. Despite a career that spanned four decades, Astrud was viewed by many in Brazil as merely João Gilberto’s wife – the girl that got lucky with that one hit record.

Mario Higa does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.