Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Astronomers announced Wednesday that a decades-long mystery surrounding the first known brown dwarf — a “failed star” called Gliese 229B — has finally been solved.

Brown dwarfs are dim, celestial objects that are between the size of a planet like Jupiter and a small star. In 1995, Caltech researchers first discovered Gliese 229B, which orbits the red dwarf star Gliese 229 about 18 light-years away from Earth. Since then, scientists have found more than a couple thousand brown dwarfs, and research in 2017 suggests there could be 100 billion throughout the Milky Way.

Gliese 229B confused scientists because the orb was deemed too dim for its size, as it weighs about 70 times more than Jupiter but doesn’t shine that bright.

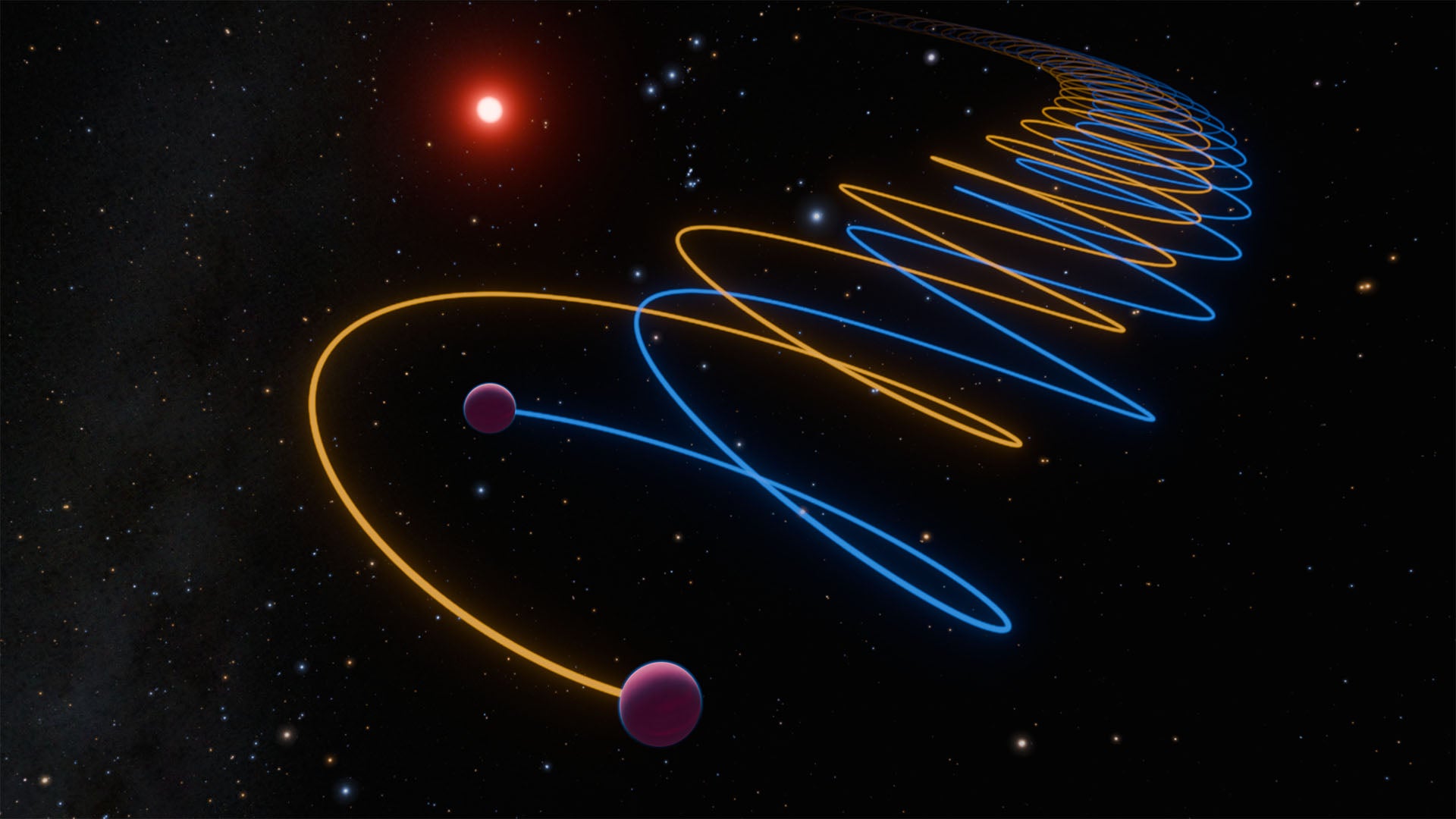

The reason for this, astronomers now say, is that the brown dwarf is actually one of two. Weighing around 38 and 34 times the mass of Jupiter, respectively, these brown dwarfs whirl around each other in a cycle every 12 days. Their brightness now matches what is expected for two brown dwarfs of this size, researchers say.

“They’d look quite strange in our night sky if we had something like them in our own solar system,” Rebecca Oppenheimer, who was part of the Caltech team that made the initial discovery, said in a release. “This is the most exciting and fascinating discovery in substellar astrophysics in decades.”

Oppenheimer, who is an astrophysicist at New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, is a co-author of the new research, which was published in the journal Nature.

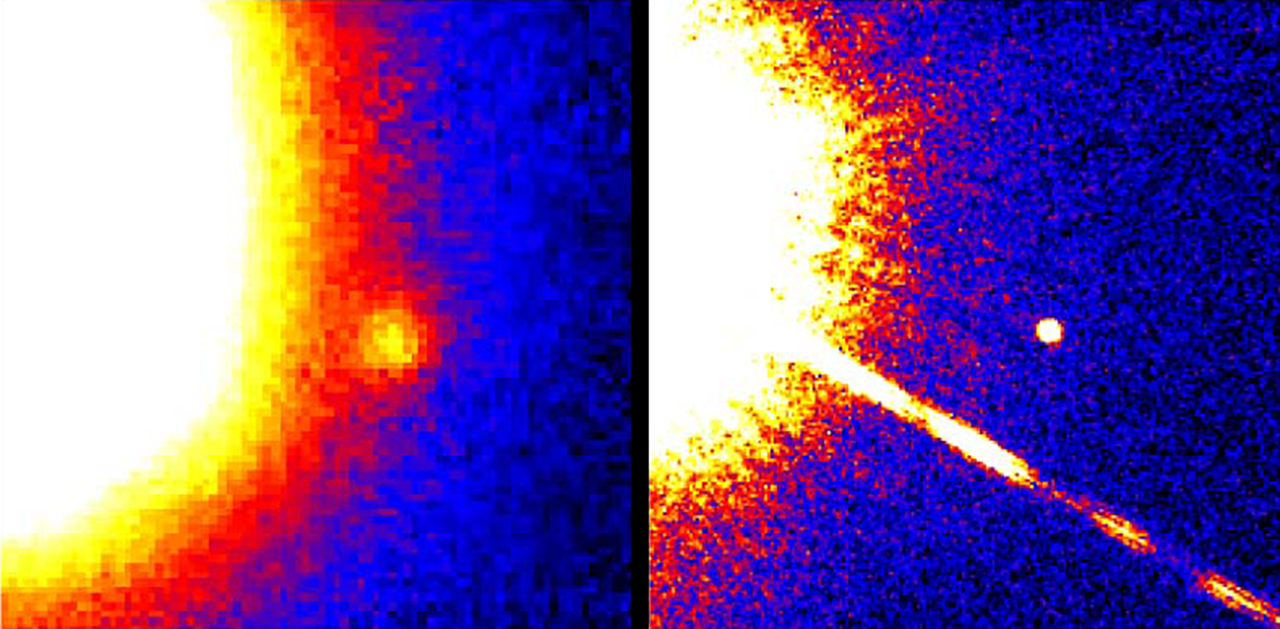

The study’s authors used instruments from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile to make the discovery, taking observations over a period of five months.

They found that the pair, now called Gliese 229Ba and Gliese 229Bb, orbit a smaller and redder star than our sun every 250 years.

Brown dwarfs do not emit much light that’s visible to the human eye, but do shine more brightly in infrared light, which can be picked up by devices like night-vision goggles or infrared cameras.

The question of how these dancing brown dwarfs came to be still remains. One theory is that pairs could form within the material that surrounds a forming star.

Of course, this discovery has resulted in new quandaries about where and if there might be similar pairs still waiting to be uncovered. In the future, the team would like to search for more pairs using other observatories.

Caltech’s Dimitri Mawet, who is also a senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says this is a major step forward.

“This discovery that Gliese 229B is binary not only resolves the recent tension observed between its mass and luminosity but also significantly deepens our understanding of brown dwarfs,” he said.