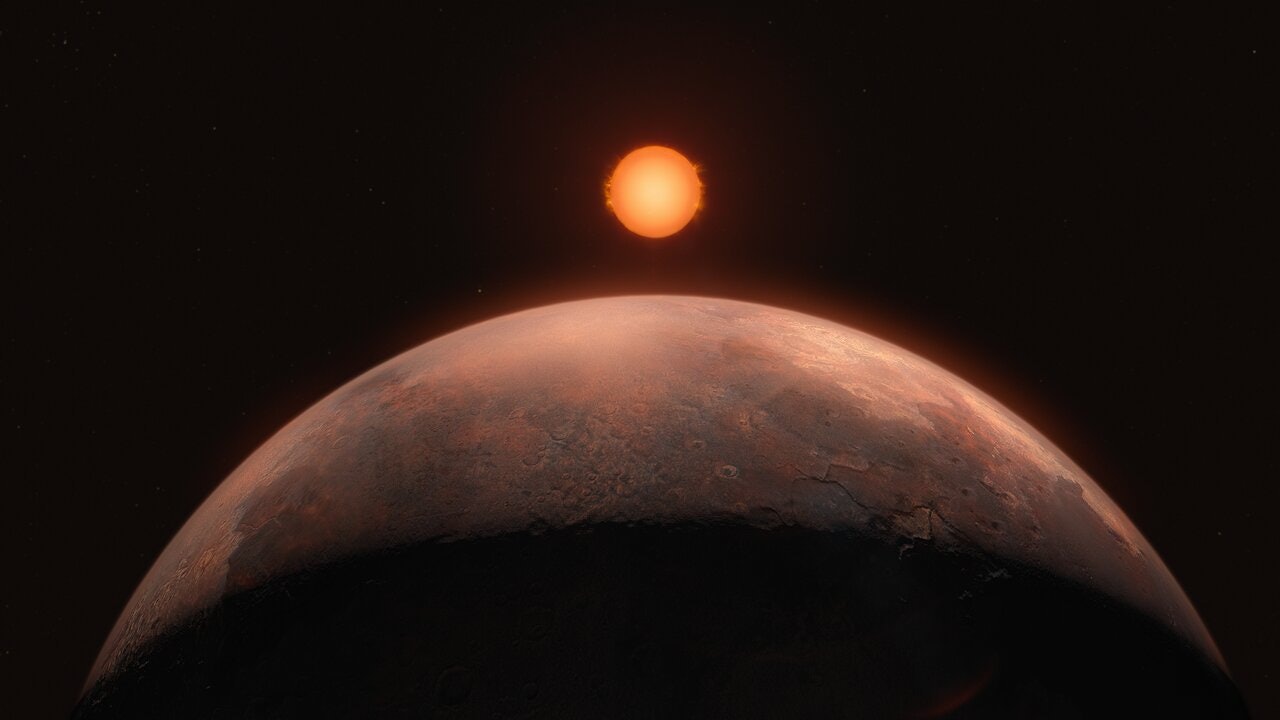

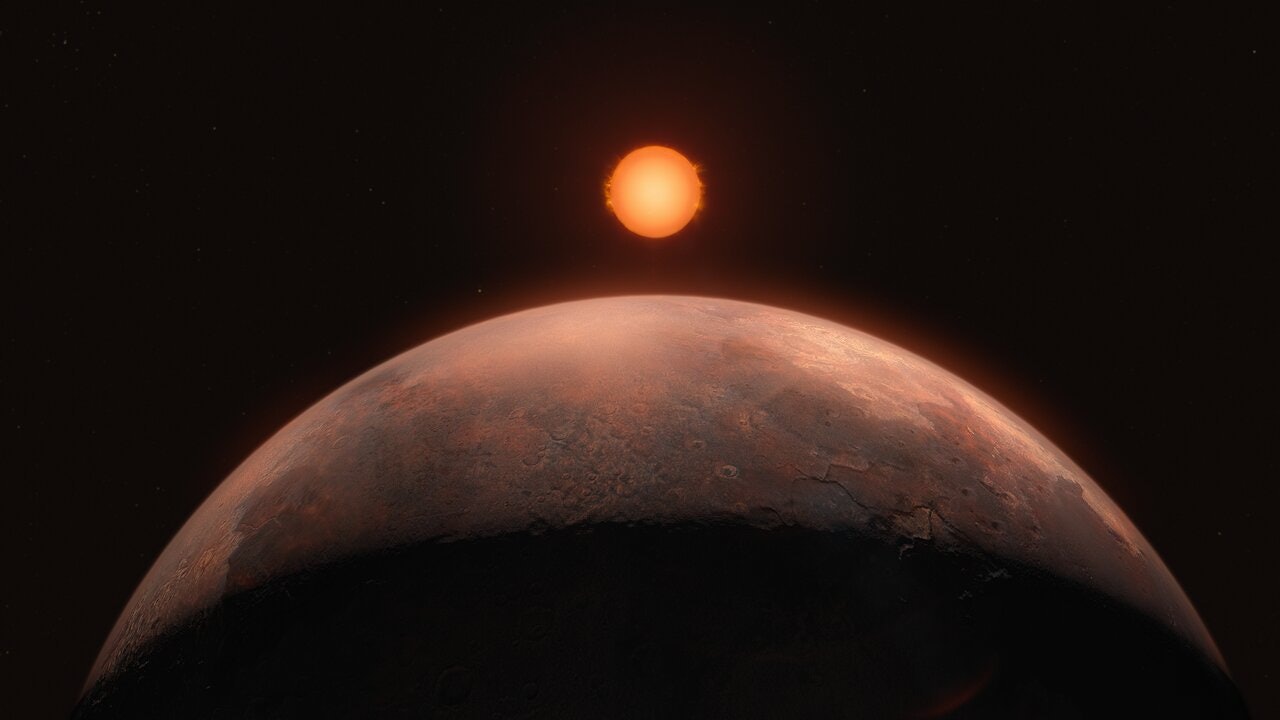

The closest single star to Earth is home to at least one planet, and it’s a rocky little world not so different from ours.

Astronomers spotted a small, rocky planet orbiting the red dwarf known as Barnard’s Star, which is about 6 light years away from Earth. While the Centauri system are our closest neighbors in space, Barnard’s Star is the nearest system that’s a single star instead of a complicated trio. Until now, astronomers weren’t sure whether it had any planets, but recent data from the Very Large Telescope (yes, that’s its real name) shows that there’s at least one small, rocky world zipping around the nearby star. The recent data also offers hints that there may be more planets around Barnard’s star, and at least one may be in the habitable zone.

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias astrophysicist Jonay González Hernández and his colleagues published their work in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

New Exoplanet Just Dropped, and It’s HOT

Hernández and his colleagues spent the last five years watching Barnard’s Star through one of the VLT’s instruments, called Echelle SPectrograph for Rocky Exoplanets and Stable Spectroscopic Observations (ESPRESSO), which measures how the wavelength of a star’s light subtly changes when the star “wobbles” under the slight gravitational tug of a planet. Measuring the star’s wobble can reveal the planet’s mass and how long it takes to complete an orbit. This is why Hernández and his colleagues can say that Barnard b, their newly-discovered world, is at least half as massive as Venus and orbits its star once every 3 (Earth) days.

That also means Barnard b is probably too hot to be livable, even for the hardiest thermophiles. To zip around Barnard’s Star once every three days, the planet would have to be just 5 percent of the distance between Mercury and the Sun. Barnard’s Star is much dimmer and cooler than our Sun, but that’s still scorchingly close. Hernández and his colleagues estimate that the planet’s average surface temperature is about 257 degrees Fahrenheit, just a little too hot for liquid water to exist on its surface.

What’s Next?

Hernández and his colleagues haven’t yet found the planet they were actually looking for: a rocky, Earth-sized world in the star’s habitable zone, or the distance from the star where temperatures on a planet’s surface should be exactly right for liquid water. But they did find a rocky planet around our nearest single neighbor, and that’s an encouraging sign that there might be more. The ESPRESSO data, in fact, hints that three more planets might also be tugging on Barnard’s Star every few days, from greater distances than Barnard b.

The team is still observing Barnard’s Star with ESPRESSO, trying to get enough data to say for sure whether those three planets exist. They’ll also need to confirm what they’ve found with other telescopes at other observatories — the same process they went through to confirm that Barnard b was real and not just a glitch in the data.

Back in 2018, another team of astronomers thought they might have found a super-Earth — a planet several times larger than Earth but not quite as massive as Neptune — orbiting Barnard’s Star, but data from other telescopes didn’t confirm its presence. Hernández and his colleagues’ recent data also didn’t support the 2018 world, which means it probably doesn’t exist.

But Hernández and his colleagues say Barnard’s Star b is an encouraging discovery.

“The discovery of this planet, along with other previous discoveries such as Proxima b and d, shows that our cosmic backyard is full of low-mass planets,” Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias astrophysicist Alejandro Suárez Mascareño says in a recent statement.