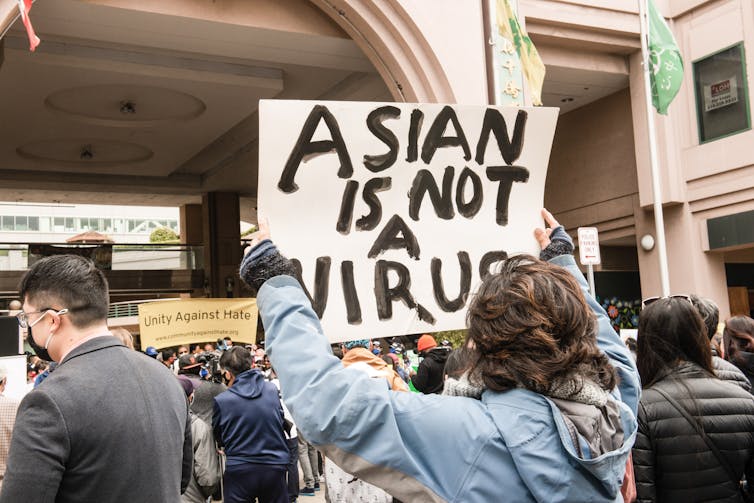

In memory of the Atlanta massage spas shootings on March 16, 2021, that killed eight people, including six Asian women, communities around the country gathered a year later to mourn and demand responses to violence against Asian Americans, especially women who work in service industries.

In addition to being exposed to risks at their workplaces, Asian American women who care for children and elders are especially vulnerable to anti-Asian violence. As sociologists and scholars of gender, race, immigration and Asian American studies, we focus on the particular challenges facing Asian American mothers.

Though they face challenges similar to those faced by other mothers confronting the COVID-19 pandemic, Asian American women have the added burden of being seen as the cause of the virus and being disproportionately targeted by hostility and violence that such misconceptions bring on.

Spike in assaults

From March 2020 to December 2021, StopAAPIHate, a joint project between the Asian American Studies Department of San Francisco State University and two Asian American community organizations, collected reports of almost 11,000 incidents in the U.S. of anti-Asian hate, ranging from spitting to verbal abuse to physical attacks. Women reported 62% of these incidents.

In a separate survey of 2,414 female Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders conducted in January and February 2022 by the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum, a national organization founded in 1998 to advocate for women and girls in that community, results show that 74% of respondents reported personally experiencing racism, discrimination or both in the prior 12 months.

The spike in violence has been reflected in news headlines that have appeared since the World Health Organization declared the pandemic on March 11, 2020.

National Public Radio proclaimed, “There’s been an alarming spike in violence against women of Asian descent in the U.S.” NBC also reported, “‘Nowhere is safe’: Asian women reflect on brutal New York City killings.”

Over the same time period, other news headlines reflected the toll the pandemic took on mothers. A New York Times headline, for instance, read “The Primal Scream: America’s Mothers Are in Crisis.” Another in USA Today read “We sacrificed working moms to survive the pandemic.”

For Asian American mothers, what appear to be distinct headlines are inextricably connected in daily decisions on whether to send children to school, accompany parents on the subway, go to work or simply leave the house.

Heightened risks

“There’s just a real sense of fear,” said Jeanie Tung, director of business development and workforce partnerships at Henry Street Settlement. The organization, located near New York City’s Chinatown, serves Manhattan’s Lower East Side residents and other New Yorkers through social services, arts and health care programs.

During an interview, Tung said she has heard from Asian American mothers that their concerns go beyond the lack of child care. “It’s more like, ‘I don’t want to work because I don’t want to risk my life,’” said Tung.

The shootings in Atlanta-area massage spas exposed the heightened vulnerabilities of Asian American women who work in high-contact service industries, such as nail salons, restaurants, delivery, health care, caregiving, hospitality and, especially, massage and sex work.

Yin Q is an organizer for Red Canary Song, a coalition of Asian massage and sex workers in the U.S., with programs also in Toronto, Paris and Hong Kong. “If you look at the rise in violence across the board,” she said in an interview, “then it’s magnified for massage and sex workers. And then you add to that, being a mother and a caregiver.”

She explained that social stigma and criminalization of their work increase their risks of violence. Their work also prevents them from being seen as devoted mothers and responsible caregivers.

John Chin, professor of urban planning at Hunter College, co-authored an National Institutes of Health-funded study that interviewed over 100 Korean and Chinese women working in illicit massage parlors.

“Can we as a community accept that a person might be both a sex worker and a loving mother dedicated to raising her children?” he asked.

Various initiatives have been proposed to address how motherhood negatively impacts earnings, known as the motherhood penalty, and how this penalty has been exacerbated during the pandemic.

Measures such as flexibility to work from home, child care subsidies, paid family leave and other programs in the Biden administration’s American Families Plan are important.

Unique challenges

On top of negotiating vaccines, mask mandates, online and in-person learning while trying to sustain their own careers and mental health, Asian American mothers are in a state of hypervigilance against racist attacks.

Immediate needs include increased personal safety. Measures such as providing alarms, rides and hotlines, as well as offering classes in self-defense and bystander training, have proved effective.

A report by the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum goes even further. “The State of Safety for Asian American and Pacific Islander Women in the U.S” urged elected officials to spend more money on community-based organizations that offer language-accessible services to help Asian Americans find employment, housing and health care.

CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities has been working since 1986 to address various forms of anti-Asian violence – from street assaults to police brutality to landlord harassment and housing displacement. Its main approach is developing leadership within Asian immigrant communities, including among tenants, workers and youths.

Queer and trans Asian American mothers, and those raising children who identify as queer and trans, are demanding visibility and responses to the particular challenges they face, including higher risk for intimate partner and family violence.

[Get The Conversation’s most important politics headlines, in our Politics Weekly newsletter.]

Asian Americans are a diverse group, as are Asian American mothers. While some Asian American groups have called for more policing, others disagree and call for community-based approaches to increase safety.

Julie Won, one of the first Korean Americans to serve on the New York City Council, told The New York Times in March 2022 that tougher policing is not the answer and more attention needs to be paid to “prevention and long-term solutions to what leads to these violent crimes.”

Education remains key

Asian American studies scholars have sought to teach the history of anti-Asian racism and specifically the roots of racialized sexualization of Asian American women.

But backlash against teaching critical race theory underscores the need to expand curriculum on Asian American history and contemporary issues facing Asian Americans beyond the university to K-12 public education. Such initiatives have been proposed in several U.S. states and have become law in Illinois and New Jersey.

Efforts to support and protect Asian Americans, particularly mothers, require approaches that both respond to the rise in anti-Asian violence at this very troubling moment and recognize the long gendered and racial histories of anti-Asian exclusion.

The authors are a married couple in addition to being colleagues at UMass Amherst. John Chin and Jeanie Tung are colleagues we have known since graduate school who have specific expertise to contribute to this article. We invited Yin Q to speak on a panel at UMass Amherst last fall.

When C.N. Le worked for the Asian Pacific Islander Coalition on HIV/AIDS as the Director of Education in New York City from 1999 to 2002, John Chin was his former supervisor and Jeannie Tung was under his supervision in her position as Volunteer Coordinator.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.