An Egyptian bust, rocket engines, dentures and knee replacements.

3D printing is not just a novelty hobby that was popularized a decade ago, when affordable printers hit the market and folks made unique plastic pieces in their homes.

Manufacturers are relying more every day on 3D printing — known inside the business as additive manufacturing.

The proof is in the numbers. The business is growing exponentially and is expected to triple in size in the next eight years to a $85.5 million industry.

“It’s growing and growing as [3D printers] become more accessible,” said Angie Szerlong, industry manager of additive manufacturing at SME.

The 3D printing business has been around for a while. SME’s annual convention was held for its 33rd year this week at McCormick Place.

The convention, Rapid + TCT, is billed as the largest 3D printing trade show on the continent, with more than 350 exhibitors and 10,000 visitors. Nearly 400 Chicago-area students were expected to visit on field trips.

The first 3D printers were developed in 1987 and were incredibly expensive, keeping them beyond the reach of most businesses. As the original patents on 3D printers expired about a decade ago, the industry saw an explosion in affordable household printers that introduced the technology to the wider public.

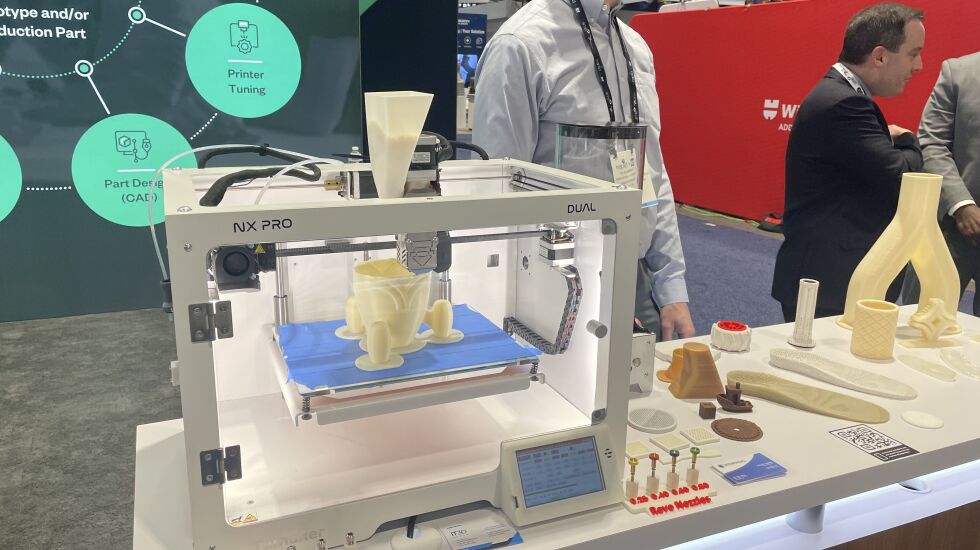

Those printers, as well as industrial printers, have gotten cheaper and better over time. Industrial printers, which can fill an entire room, can also create metal and ceramic parts. They can build car parts and rocket engines.

“You can get a great machine now for $4,000 versus $1 million” before, Szerlong said.

Manufacturers are adopting 3D printers because they can produce cost-effective custom parts that traditional manufacturing methods can’t.

This shift in manufacturing may lead companies to offer consumers more customizable products in the future, Szerlong said.

Think of custom shoe insoles designed just for one person, or clear retainers from your dentist. Or custom hearing aids and sports equipment like helmets and hockey sticks.

“That’s all made possible because of 3D printing,” Szerlong said.

This type of manufacturing is seen as more sustainable because the printers use only the material printed instead of large amounts of materials like blocks of steel used in traditional CNC machining, she said.

Aerospace companies also rely on the technology.

“You can’t find an aerospace or space company right now that’s not printing,” said Fred Carter, head of research and development at DMG Mori.

DMG Mori has its North American headquarters in suburban Hoffman Estates and builds industrial 3D printers in Davis, California, which it sells to companies in the aerospace, automotive and medical space.

Carter held up a pneumatic manifold that his company printed from metal. He said the piece, too complicated to be constructed by other means, was built specifically for the company’s 3D printers.

Top-end 3D printers still cost around $2 million to $3 million, keeping them out of reach for many manufactures.

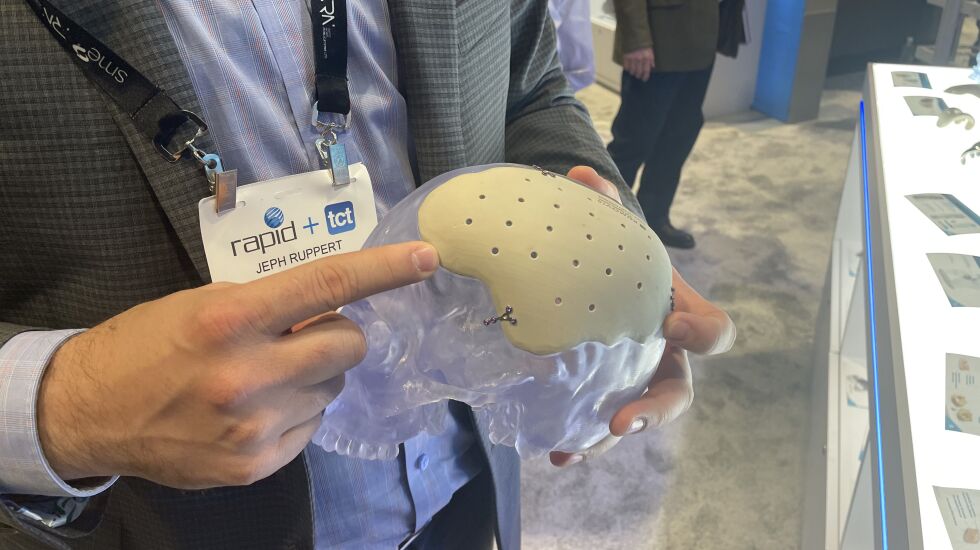

So some companies like 3D Systems specialize in making custom-order parts for other companies, said Jeph Ruppert, the firm’s vice president of technical business development.

The South Carolina-based company’s printers are used to make wax castings for jewelry manufacturing, which is a bigger part of the 3D printing business than people realize, Ruppert said.

But doctors and dentists now have 3D printers of their own and can create prosthetics and dentures in-house for patients.

Met-L-Flo Inc., based in Sugar Grove, Illinois, near Aurora, shifted from metal forging to 3D printing in 1989. The company on Tuesday displayed a miniature model of the Art Institute of Chicago’s lions. The lions were scanned in 2015, according to Met-L-Flo program manager Katie Peterson.

Women are underrepresented in the 3D printing business. They account for 11% to 13% of the workforce, according to Sarah Goehrke, board director of Women in 3D Printing.

The nonprofit, founded in 2014, promotes a more diverse workforce. But the issue with female underrepresentation in engineering extends all the way to the U.S. education system, which sees many women pushed out at young ages.

“We want to see the industry succeed and see people equipped to do the best work they can do,” she said.