2025 was a challenging year for climate politics, and a challenging one for our warming planet.

In the past 12 months, climate change has been impossible to ignore, whether we would like to or not. Euronews takes a look back at a year of record highs and lows.

The 11 warmest years on record

Let's start with some climate facts for 2025, which make for sober reading.

The World Meteorological Organisation has already said that the past 11 years were the warmest on record, and 2025 is most likely to be either the joint second or third warmest year on record.

The final tally in January is expected to show that the last three years all surpassed the 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels goal set out in the decade-old Paris Agreement, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

So why is this happening? Greenhouse gas concentrations hit a record high in 2025. These gases are produced by human activities like the combustion of fossil fuels and from changes in land use linked to deforestation and industrial agriculture. The gases trap heat from the sun faster than the atmosphere radiates it back into space, creating global heating.

Trump calls climate change a 'con job'

The year started with Donald Trump in the White House, again, as Forrest Gump would say, and pulling the US out of the Paris Agreement, again. It was a campaign promise to American voters, and he stuck to the script.

What was a little more off-script was Trump's speech to the United Nations General Assembly in September, in which he said renewables were a “joke” that were “too expensive”. He captured headlines with one particular zinger, describing climate change as "the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world".

Trump lifted the freeze on liquified natural gas (LNG) export approvals the day he came into office, and since then, US sales have soared.

LNG is a fossil fuel often promoted as a means to 'transition' to renewables, yet the associated production and transport of LNG make its emissions 33 per cent higher than coal. America supplied almost half of Europe's LNG this year.

So, in the snakes and ladders game of emissions reduction, the US slid down a snake in 2025, while its rival China climbed a few ladders. Although it remains the world's biggest emitter, analysis from Carbon Brieffound that China's CO2 emissions have been flat or falling for 18 months.

Did China just peak? Possibly. The country saw dips in emissions from transport, steel and cement production, and the country's fossil fuel power plants should have their first annual drop in generation in a decade this year as a result of the massive expansion of renewables to meet rising demand.

In Brussels, the EU's climate and energy policy seemed more like a Christmas puzzle in 2025. Just recently, it wound back on plans to abolish the sale of internal combustion engine cars from 2035. This came only a few days after it finally sealed the deal on a legally binding target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 90 per cent compared to 1990 levels by 2040. Are those two both technically and politically compatible?

Pieces of the Green Deal legislation were slid around the puzzle for months as part of the Omnibus I package, proposed in February 2025. Meant to 'simplify' rules, it was widely criticised for backsliding on standard-setting environmental laws, and offering critics of 'net zero' an easy chance to score points. The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, due to come into force on New Year's Day 2026, was relentlessly pushed and shoved around by industries over exactly how it should be applied and who can claim to be exempt.

Amnesty International called Omnibus I a 'bonfire' of regulation, while BLOOM described Europe as entering 'democratic darkness'.

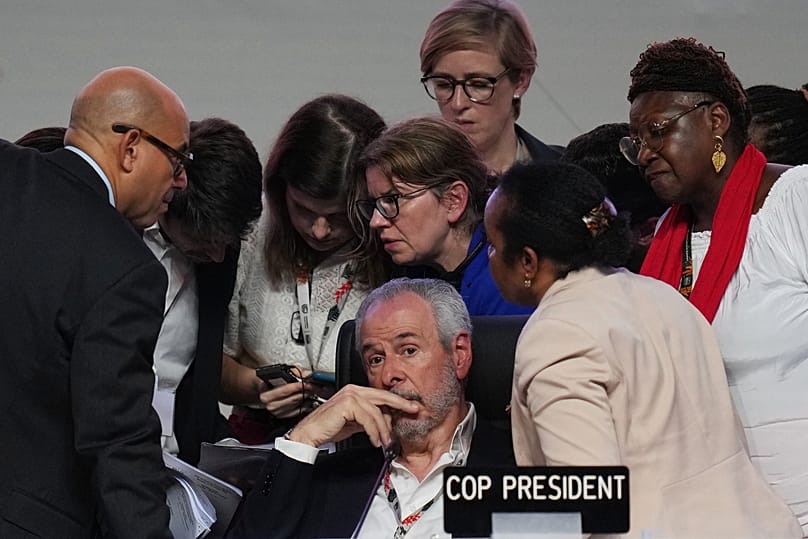

In November, the COP30 climate summit also saw a few fiery moments, not least when part of one pavilion actually caught ablaze. Hosted in Brazil, on the edge of the Amazon rainforest, it has been praised for two things.

Firstly, after three previous COPs hosted in anti-democratic and authoritarian countries, the climate campaigners could at least make themselves seen and heard a little more easily this year. Secondly, in the absence of easy progress on the UNFCCC's Paris Agreement objectives, a series of coalitions between more climate-friendly countries began to emerge. It signals a fresh departure from the status quo that pits the eager and willing against the cranky and reticent.

Overall, COP30 wasn't viewed as a success, with the well-respected Climate Action Tracker describing it as 'disappointing', with 'little to no measurable progress in warming projections - for the fourth consecutive year'. They calculate we are currently on track for warming of 2.6 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial averages by 2100, and warming continues into the next century.

Ice melting, seas rising, land roasting

Meanwhile, in the most remote parts of the planet, changes are accelerating, amid fears that irreversible planetary tipping points are being passed. If the politics of climate change in 2025 doesn't leave your head spinning, then the reality of the warming over land, across the cryosphere and in the oceans probably will.

Firstly, look up and enjoy the view of any icy peaks while you can, because they won't be around for long. A 2025 study from ETH Zürich found that we're about to enter a period they label 'peak glacier extinction'. Places like the Alps, the Rocky Mountains, the Caucasus, and the Andes will change forever.

This year, it was confirmed that Venezuela haslost its last glaciers. By 2100, Central Europe will have a mere three per cent of today's total number of glaciers following current warming trends. This has profound implications not only for beautiful tourist hotspots, but also for hydropower and farming communities that rely on meltwater in summer. The related dangers of glacier collapse were brought to the world's attention when the Swiss village of Blatten was crushed by a torrent of ice, mud and rock in May.

Elsewhere, astudy published in June 2025 turned heads as it simulated the collapse of the AMOC, the conveyor belt of heat from the equator that keeps northern Europe mild and wet. There's no timeline, but the modelling is extraordinary. In a moderate emissions scenario with a rapid slowdown of the ocean currents, there would be sea ice reaching Scotland and winter temperatures in London as low as -20 °C. Northern Europe would be the only part of the planet to get colder, rather than warmer.

In the Antarctic, researchers have also been watching the ice shelves destabilise. A team from the University of East Anglia in the UK, using the fabulously-named British research submarine Boaty McBoatface, carried outthe first ever survey of the 'grounding line' beneath the Dotson Ice Shelf, the spot where the glacier floats onto the sea. They found that the water deep inside the cavity was 'surprisingly warm', and they're now rushing to explain how it got there.

In Greenland, it was a long summer. Scientists from the Danish Meteorological Institute found that ice melt began in mid-May 2025 and continued into September. That means that summer arrived 12 days earlier than the 1981-2025 average, and the territory lost 105 billion tonnes of ice in the 2024-2025 season.

That melt is one of the factors contributing to the steady acceleration of sea level rise. We don't have figures for 2025 just yet, but in 2024 we saw a record 5.9 millimetres of sea level rise, and the 2014-2023 average is now 4.7 millimetres per year.

Coastal communities worldwide are now paying attention and demanding action, even in Trump's America. On the South Carolina coast, where Forrest Gump fished for shrimp, local people are coming together to document the high tides in a citizen science project organised by the South Carolina Aquarium. If you're into murky pictures of rising water, it's the place for you.

Looking back at the last 12 months, there's a long list of natural disasters amplified by climate change. Mexico and Sri Lanka experienced flooding and landslides, while exceptional rains in Indonesia and Malaysia left hundreds dead and hundreds of thousands displaced. Cuba and Jamaica were smashed by Hurricane Melissa.

Five years of drought have turned the Fertile Crescent into a dustbowl. Iran, Iraq, and Syria are also facing severe and potentially catastrophic water shortages. Droughts have always occurred in these regions, but rapid analysis by the scientists at World Weather Attribution found that a year-long drought would only be expected every 50 to 100 years in a cooler, pre-industrial climate,and it's expected to return every 10 years today.

In Europe, there wererecord emissions from wildfires this summer, according to the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service. Just under 13 gigatonnes of CO2 were released, and PM2.5 air pollution was above WHO guidelines across large parts of Spain and Portugal.

In terms of temperatures, there were fresh highs around the world this year. Although 2025 won't rank at the top, it was still an exceptionally warm year. Finland saw repeated temperatures above 30°C over a two-week heatwave, Türkiye hit a new national high of 50.5°C, while similar temperature readings were seen in Iran and Iraq. Station records were beaten in China, and Japan faced an extended summer, with 5 August 2025 hitting a new national temperature record of 41.8°C.

What does 2026 have in store?

In 2026, the UK's Met Office outlook suggests that we will experience one of the four warmest years on record.

Professor Adam Scaife, who leads the global forecast team, said: “The last three years are all likely to have exceeded 1.4°C and we expect 2026 will be the fourth year in succession to do this. Prior to this surge, the previous global temperature had not exceeded 1.3°C.”

Looking further ahead, anticipation is building around the first international conference on the 'Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels', due to take place in Colombia on 28th and 29th April, co-hosted by Colombia and the Netherlands.

The event will be held in a major coal port, and the objective is to shift the needle on climate-friendly policy.