People in prison rarely get to go to college.

But an expansion in access to federal financial aid through Pell Grants for those who are incarcerated will soon make higher education a bit more available.

As of 2014, only 15% of people earn a college degree or postsecondary certificate either before or during their incarceration. Among U.S. adults as a whole in 2021, 53.7% earned such degrees.

Joshua Dankoff, who works as director of strategic initiatives at the nonprofit Citizens for Juvenile Justice, collects data on prison education. He found that in Massachusetts, where I live, nearly 2,000 of the 5,300 people in Department of Correction custody are on college or vocational education waitlists. Only 213 are enrolled in some form of postsecondary education. Just 77 are enrolled in a bachelor’s program.

The reason so few U.S. prisons offer college education is due to a 1994 crime bill that banned federal financial aid to people in prison.

The Second Chance Pell Experiment, launched by the Obama administration in 2015, reinstated Pell Grants for incarcerated students who are Pell-eligible. To apply for Pell, students must qualify via the Free Application for Federal Student Aid form, or FAFSA, and be enrolled in college through a Pell-eligible institution while in prison.

The program initially covered just 67 programs. An additional 67 were added in 2020.

The Biden administration is expanding Second Chance Pell access by adding 73 schools, including 24 historically Black colleges and universities. Beginning July 1, 2023, up to 200 higher education programs will serve incarcerated students.

As the director of the Emerson Prison Initiative at Emerson College, I believe it’s important to distinguish between the different educational programs offered within prisons.

There are three main types. The first includes high school equivalency and vocational programs run by departments of correction. The second is educational non-credit-bearing programs offered by outside volunteer organizations, such as gardening clubs or Toastmasters. Third are credit-bearing degree programs run by outside colleges and universities, like mine.

Prison-run education programs

Many U.S. states such as California, New York and Massachusetts provide adult basic education, or ABE. Some also mandate access to English language instruction. ABE is meant to improve literacy and numeracy and offer the opportunity for incarcerated people to get a high school equivalency diploma. Many prisons also offer computer classes and other supplemental, non-credit-bearing courses.

Researchers call educational opportunities like these “prison education.” The programs are designed and carried out by correctional staff.

Although prison education programs may strive for universal benchmarks such as passing HiSET or GED high school equivalency tests, the guidelines for who can participate are set by prison administrators in partnership with state agencies.

For example, in Massachusetts, the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education provides curricular standards and funding for adult basic education and testing both within and outside of prison. Currently, 961 people incarcerated in Massachusetts are on the waitlist for ABE. And while the state Department of Correction received funding for just under 200 ABE spots per year in recent years, it did not request funding for the next five years, suggesting that fewer people will have access to prison education.

Further, while incarcerated young people under age 22 with an identified disability and no high school diploma have a right to special education services, Dankoff analyzed Massachusetts data and found that only a fraction of young people in this situation actually receive these services. This is largely because jails and prisons do a poor job identifying young people with special education needs. It is also because the systems are oriented toward punishment rather than education.

College-run programs in prison

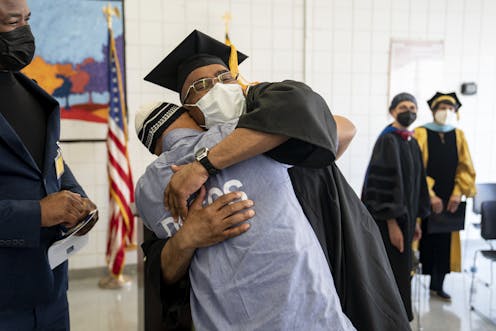

Prisons also allow education programming through outside partnerships with colleges and universities. Students in “college in prison” programs are usually enrolled into college-level degree-granting programs, including certificates, associate and bachelor’s degrees. These are the types of programs that will grow under the Pell Grant expansion.

Many colleges and universities that bring their programming inside prison walls try to provide an education for incarcerated students that is comparable to what they provide traditional college students. Educators from the outside come into the prison to teach. The programs often offer library research support, accessibility services and academic advising as well – in line with best practices for colleges in general. However, they must adapt to censorship restrictions within prisons, as well as limited internet and technology access, along with a host of additional regulations.

Power of language

In my experience, many prison educators are dedicated to the transformational power of education, just like their college-in-prison counterparts.

However, another small but I believe important difference is that prison-run programs typically refer to incarcerated students as “prisoners” or “inmates,” continuing Department of Correction language choice. In contrast, programs like the Emerson Prison Initiative refer to the people we work with as “students,” “applicants” or “students who are incarcerated.” This language treats incarcerated students with respect and dignity, which I’ve argued is central to student success and well-being.

The expansion of Pell Grants to more incarcerated people offers an opportunity to make college in prison more available while also maintaining best practices in this rapidly growing field. Such practices include little things, like the labels we use to refer to students, and big things, like ensuring that those who draw Pell Grants enroll in rigorous programs where they get a quality education and earn a degree.

Mneesha Gellman is the director of the Emerson Prison Initiative, which receives funding from the Cummings Foundation, Gardiner Howland Shaw Foundation, Emerson College, and individual donors.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.