Australia is welcoming back international students in much greater numbers this year. Some predict new enrolments in 2023 could even be higher than the pre-COVID record in 2019. Student visa applications in the second half of 2022 were up 40% on the same period in 2019.

The downside is many of these students are likely to struggle to find affordable and adequate accommodation. They are facing record low private rental vacancy rates and higher rents than before the pandemic.

Redfern Legal Centre’s International Student Legal Service NSW has been assisting international students for over a decade. Its senior solicitor, Sean Stimson, told us:

The tenancy situation facing international students in the second half of 2022 – including illegal evictions and illegal rent increases – is the worst I’ve seen. We are increasingly seeing international students who are occupying substandard, illegal accommodation, exposing themselves to dangerous environments.

To make matters worse, a number of universities have been selling off a proportion of their student housing in response to falls in revenue during the pandemic. For example, in 2021, University of Technology Sydney sold three buildings with 428 beds for A$95 million to Scape, the largest provider in Australia’s A$20 billion purpose-built student housing sector.

In some cases, this has made student accommodation more costly. Rents are typically equivalent to, or even higher, than rents in the wider private rental market.

Like any group, students’ financial resources vary greatly. However, little was known about these inequalities and their impacts on international students’ housing and everyday living.

Our recently published study, involving more than 7,000 international students, shows many were struggling financially even before the post-COVID rental crisis. They suffered great anxiety about finding the money to pay the rent and worried about becoming homeless.

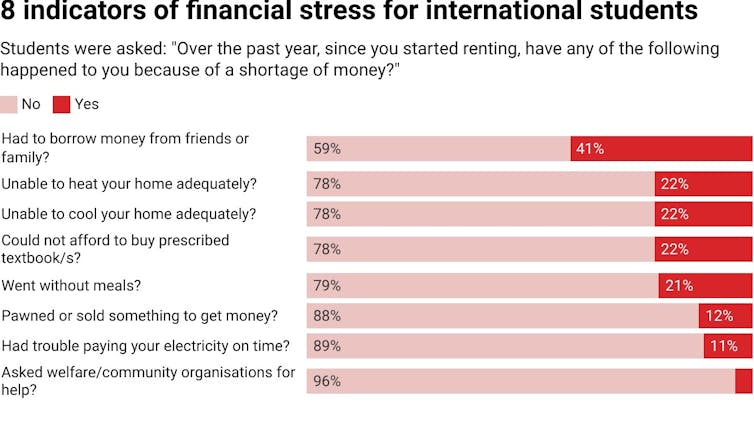

We also found food insecurity was common among these students. More than one in five had gone without meals. Similar numbers were unable to heat or cool their home adequately.

What did the study look at?

To study students’ experience of financial hardship or precarity, we used a scale of seven financial stress indicators from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. We added a new item, “Could not afford to buy prescribed textbooks”.

Our research project surveyed students who depended on private rental accommodation in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia’s top destinations for international students, in late 2019.

The sample was drawn from all three post-secondary sectors. It included ten universities, 24 vocational colleges, seven English language colleges and two foundation course institutions.

We divided the 7,084 valid responses to the survey into four groups: secure (no financial stress indicators), moderately precarious (one to two indicators), highly precarious (three to five) and extremely precarious (six to eight).

Some 44% of students were secure, 31% were moderately precarious, 20% were highly precarious, and 5% were extremely precarious.

How many students are struggling financially?

A large proportion of students were struggling, as the chart below shows. Some 21% reported going without meals in the past 12 months. And 22% were unable to heat or cool their home adequately.

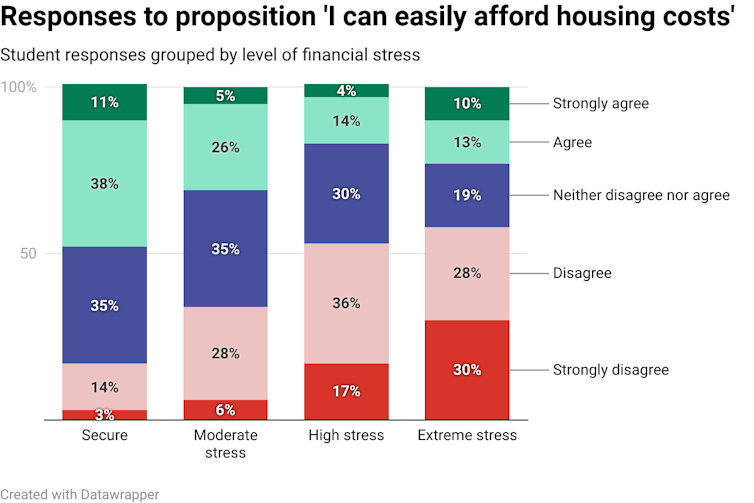

How affordable is students’ housing?

More than half of the students classed as highly and extremely precarious (53% and 58% respectively) said they could not “easily afford housing costs”. This compared to 34% of moderately precarious and 17% of secure students.

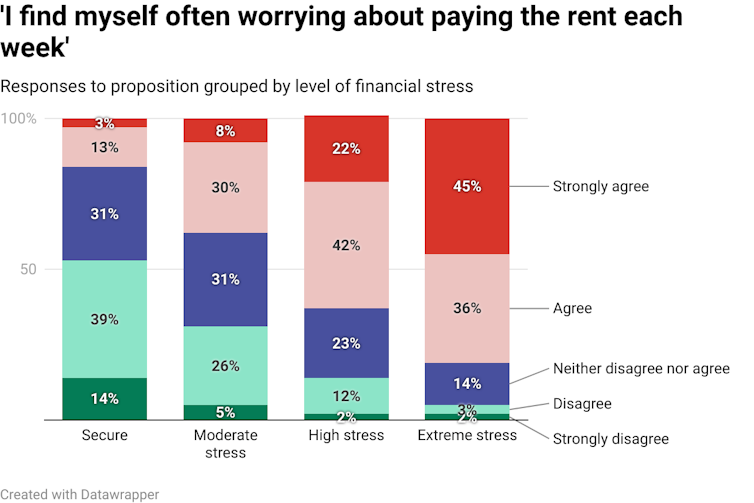

Paying the rent was a source of much anxiety across all groups. Some 64% of highly precarious students and 81% of extremely precarious students said they often worried about paying the rent each week, compared to 38% of moderately precarious students and only 16% of secure students.

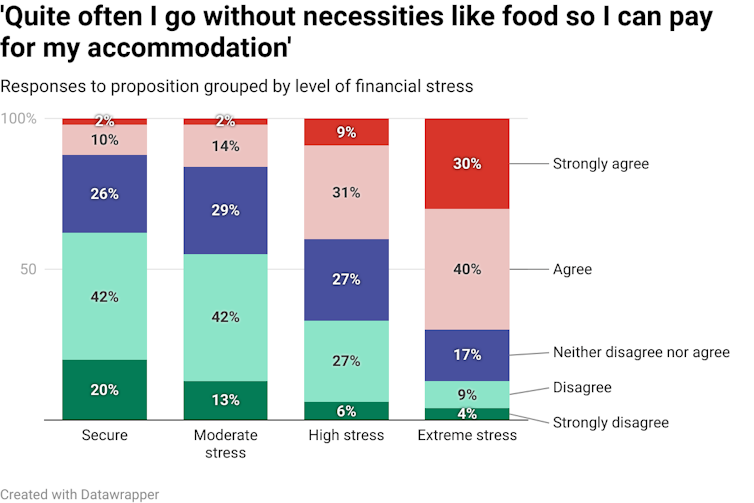

Worryingly, 70% of extremely precarious students reported going without necessities such as food so they could pay the rent. This proportion drops to 40% for highly precarious students, 16% for moderately precarious students and 11% for secure students.

Read more: How many Australians are going hungry? We don't know for sure, and that's a big part of the problem

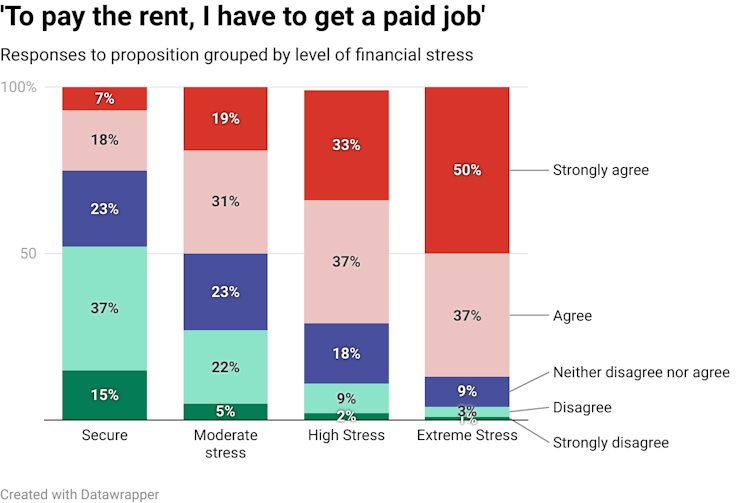

Many international students have a job and paid work is strongly related to precarity. A large percentage of extremely precarious students and highly precarious students (87% and 70% respectively) agreed having paid work was essential to pay the rent. In contrast, half of moderately precarious students and a quarter of secure students said they needed paid work to pay the rent.

Severe financial need may drive students into accepting underpaid or unsafe work.

How secure do students feel about their housing?

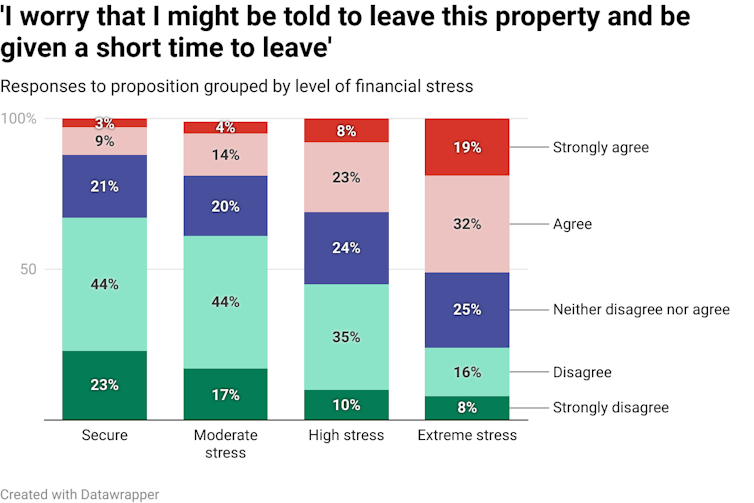

High rents are only part of the housing insecurity problem. When asked whether they worry about being told to leave their accommodation at short notice, just over half of extremely precarious students said yes, as did 31% of high precarious students. Only 18% of moderately precarious students and 11% of secure students had similar worries.

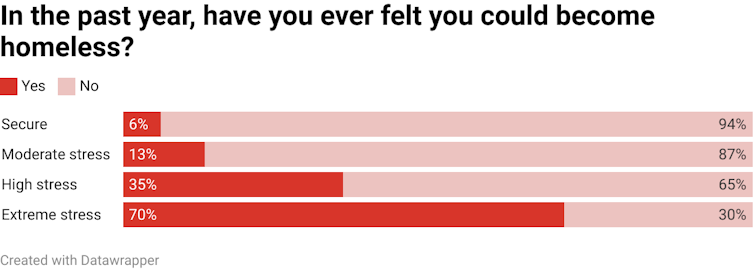

A particularly worrying finding was that seven in ten extremely precarious students and just over one in three highly precarious students had felt in the past year that they could become homeless. Only 13% of moderately precarious students and 6% of secure students had this concern.

Read more: As international students return, let's not return to the status quo of isolation and exploitation

Looking ahead

The rental housing crisis means the circumstances of international students in need of housing are likely worse now than in late 2019.

The risks are particularly high for students from poorer backgrounds or countries. Policymakers and education providers must pay more attention to the issue of housing students who come to study in Australia.

Alan Morris receives funding from the Australian Research Council

Luke Ashton receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Shaun Wilson receives funding from the Australian Research Council

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.