Why would early 20th-century Australian women travel across the Pacific to the United States? And if they left, why wouldn’t they go to England, the “mother country”, where there was a proper cup of tea? The US was no feminist utopia. It did not give federal voting rights to women until 1920 – 18 years after Australia.

The ten Australian women Yves Rees profiles in Travelling to Tomorrow: The Modern Women who Sparked Australia’s Romance with America felt differently. For good reason. Australia, Rees writes, gave women the vote, but it gave them little power or influence to achieve their dreams outside the home.

Review: Travelling to Tomorrow: The Modern Women Who Sparked Australia’s Romance with America – Yves Rees (NewSouth)

These ten women recognised Australia’s rusted-on resistance to their ambition and voted optimistically, fantastically, for a life in the US. Their success stateside shows that, in the early 20th century, the US was more open to women progressing professionally than the struggles of suffragettes suggested.

The women Rees discusses are little known, despite their achievements. Rees often received blank stares when mentioning the women’s names even to other historians. The hidden histories of each of these women is playfully and pointedly described in the book’s chapter headings, which refers to them by their profession, rather than their name.

There is “the lawyer” May Lahey, who graduated from University of Southern California Law School and in 1914 was admitted to practise. Later, in 1928, as a Californian judge, the Queenslander was the first women in the world to claim the honour of “your honour”.

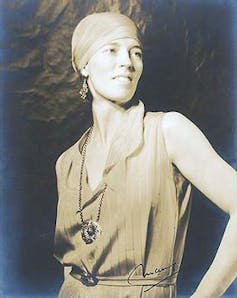

In New York, Rees found “the decorator”: blue-haired social climber Rose Cumming and “the artist”, Mary Cecil Allen. In San Francisco, “the swimmer” Isabel Letham was a “freshwater mermaid”, who taught San Francisco’s ladies how to swim. “The pianist” Vera Bradford and “the nurse” Cynthia Reed – who would later marry Sidney Nolan – both lived in Chicago.

Rees squeezes in “the writer” Dorothy Cottrell, “the economist” Persia Campbell, “the health guru” Alice Caporn and “the dentist” Dorothy Waugh.

All ten deserve their own biographies. Rees has previously written singular essays for The Conversation on Letham, and Cottrell, “the Liane Moriarty of the jazz age”. But the power of a collective biography – formally known as a “prosopography” – is that the individual stories, when brought together, reveal bigger emotional, cultural and political truths.

Disruptors and influencers

In all, Rees found 700 Australian women who emigrated to the US in the early 20th century. When these women returned, if they returned at all, they attempted to change the status quo in Australia. In that vein, Travelling to Tomorrow uncovers a new history of women disruptors and provides an alternative lens on Australia’s relationship with the US. Rees writes:

Decades before Prime Minister John Curtin announced Australia’s turn to America in 1941, and the ANZUS treaty was signed in 1951, these Australian women sparked Australia’s romance with America.

The ten women Rees has chosen to feature in Travelling to Tomorrow were not the first to set sail. In 1902, Vida Goldstein met with President Theodore Roosevelt in the “fish room” of the White House during her tour of the US. Goldstein’s meeting occurred decades before economist Persia Campbell, a single mother, became an advisor to President John F. Kennedy in 1962.

By 1906, novelist Miles Franklin and journalist Alice Henry were working in Chicago, well before Vera Bradford arrived in 1928 as winner of the Percy Grainger fellowship. Cynthia Reed, sister of art patron John Reed, dodged immigration to study nursing in the Windy City in 1935. Reed only left “the Yanks” to continue nursing in the UK because she was caught without a visa.

Travelling to Tomorrow is not focused on who was first. Rees is more intrigued by why these women left and how they changed Australia. Artist and educator Mary Cecil Allen returned in 1935, but was decreed to have “an unfortunate addiction to modernism”. Allen was undaunted, and Rees argues she was ultimately influential in convincing the conservative Australian art world to embrace modernism.

Letham, “the mother of Australian surfing” as well as a freshwater mermaid in the pool, was less successful. The Surf Life Saving Association of Australia refused to allow a woman to export their rescue techniques to an enthusiastic US. This stubbornness was despite her profile as one of San Francisco’s best swimming teachers, who had surfed with Hawaiian Duke Kahanamoku when he visited Sydney.

Others were clearly ahead of their time. Caporn, a wellness guru and “ambitious hustler”, would have thrived on Instagram and TikTok today. After she returned to Perth in 1937, she infuriated the Australian dairy industry by promoting non-dairy alternatives such as almond milk. She also advocated salads when vegetarianism was called a cult.

The 11th character

There is an 11th character in Travelling to Tomorrow. Throughout, Rees reflects on their own relationship with the US. More deeply, they reflect on how their trans journey relates to their identification with these disrupting women.

In personal, exquisitely written interludes, Rees breaks with the dispassionate tradition of historical writing. In the chapter “HerStory Whose Story”, they write that when they first began researching Australian women in the US, it was from “a position of identification”:

They were women; I was a woman. Like them, I was a white Australian with the privilege and appetite to orientate my life around travel and education and career. They felt, in many ways, like a version of me born a century earlier.

By the end of their research, Rees has a very different view:

But all the while the feelings raged. All the while, I was running towards Mary Cecil Allen and Isabel Letham and May Lahey and all the others […] a hot mess of gaping need. How do I do this strange thing called womanhood? What does it look like to be a woman and be sovereign over yourself?_ …

You can probably guess how this story ends.

These interludes allow Rees to be an observer and offer a Pacific-wide view of the contemporary US. They remind us that the country is enmeshed in a dystopian and regressive anti-trans agenda.

But Rees resists writing a revisionist trans history of the women in Travelling to Tomorrow. Rather, they leave the question of the women’s identities as part of the complexity of their stories. Rees notes that May Lahey “never married and characterised single career woman such as herself as a kind of ‘third sex”.

Mary Cecil Allen preferred pants, and to be known by her middle name. Cynthia Reed had a breast reduction. Rees asks:

…who was to say how female-assigned people from history would have understood their gender assignment if they’d had concepts like nonbinary and genderqueer at their disposal? The possibilities of self-definition are always shaped by historical context.

Such interludes contribute to the book rather than distract, because Rees uses their voice to illustrate how we can identify and idealise people and countries, interpreting them in light of what we want them to represent.

Not all readers will agree with Rees’s inclusion of their own story. I know myself, as the author of A Wife’s Heart – a single parenting memoir combined with a post-separation biography of Henry Lawson’s wife Bertha – that some reviewers and readers enjoy the relationship between the author’s story and their subject, while others are resistant, finding it distracting or unnecessary.

Rees may well expect this mixed response. In including so many strong identities, alongside Rees themself, Travelling to Tomorrow is a structural challenge.

Rees has chosen to weave the stories around each other, and concentrate on the thematic arc,rather than present a chronological, woman by woman account. The result is like a modernist painting, of the kind Mary Cecil Allen dedicated her life to promoting. At first glance, it presents a clash of competing elements. Then the intricate details and relationships become clear – and it harmonises as a historical whole.

Kerrie Davies does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.