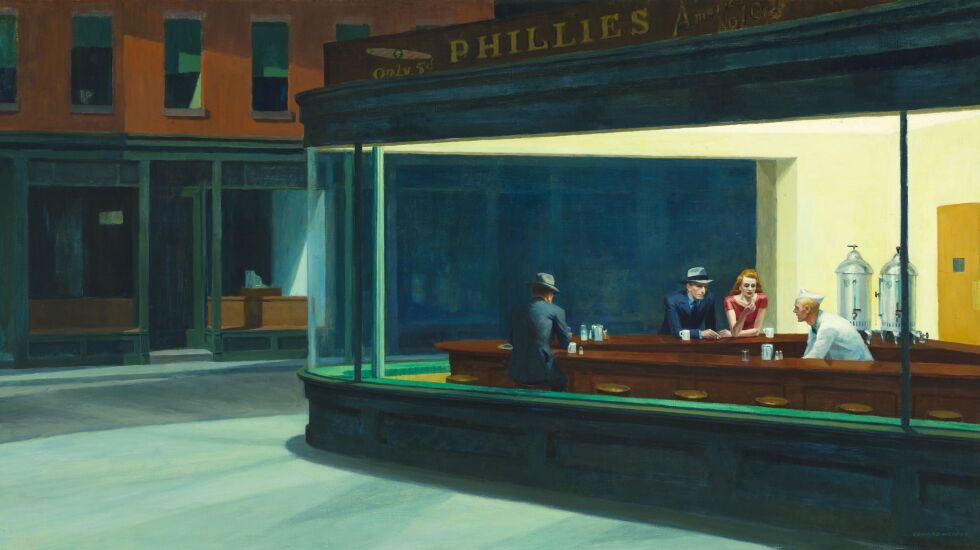

Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks,” an iconic 1942 painting of a corner diner in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, is the artist’s most famous work.

But familiarity doesn’t make it any easier to decode. The restaurant has no obvious entrance and no sign. Almost no food is being served or eaten. And the empty streets outside look as much like a movie set as a real city.

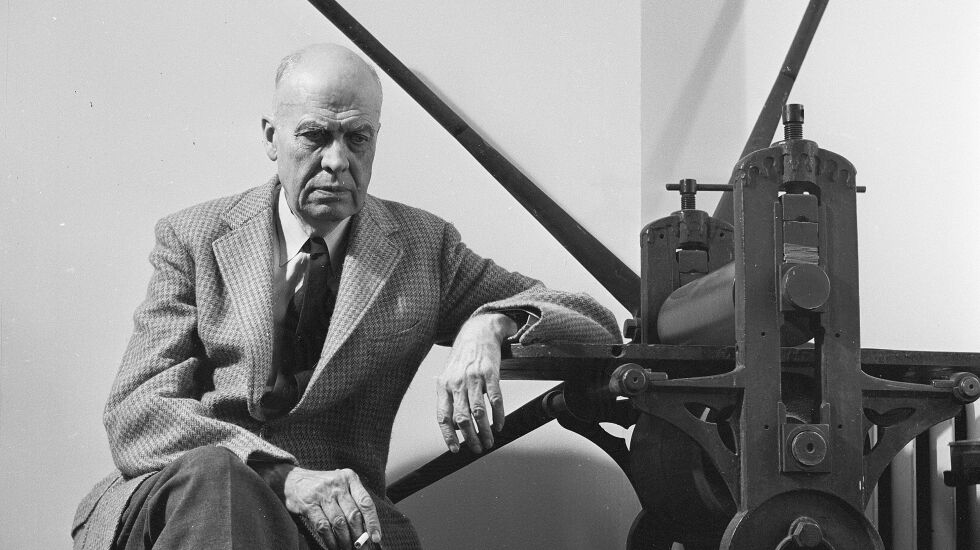

It is mysterious and inscrutable, just like Hopper (1882-1967), who is profiled in an engaging and insightful film that will premiere at 8 p.m. Jan. 2 on WTTW-Channel 11 as part of the “American Masters” series on PBS. It is the first-ever, in-depth documentary on this essential American painter — one that was long overdue.

“Hopper is one of the rare artists whose work is publicly popular and critically acclaimed at the same time, and it frankly dawned on me that nobody had ever done a proper biographical documentary,” said Michael Cascio, who wrote and directed the film along with Phil Grabsky.

Its subtitle, “An American Love Story,” suggests a double meaning: Hopper’s affinity for all things American as well as his long marriage to Josephine “Jo” Nivison Hopper. They met in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 1923, and discovered among other things that they were both fans of the French poet Paul Verlaine.

Jo’s story is a major emphasis of this documentary, and deservedly so. She is another on a long list of undervalued artist wives who sacrificed their own careers, becoming, in her case, a model, business manager, marketer and caretaker for Hopper.

An early surprise in the documentary is seeing side-by-side paintings of Gloucester by the two artists and learning that Jo was more commercially successful at the time. In addition, the documentary explains how she influenced his palette, with his colors becoming more spontaneous and expressive.

It was a tough marriage for her, because he could be distant, subsuming and even mean, as her diaries make clear, but it somehow seemed to work. One of the documentary’s final images is footage of the two late in their lives sitting together on a bench in New York’s Washington Square Park within eyeshot of their apartment.

“The great revelation was that you can’t understand Edward without understanding Jo,” said Grabsky. “They are a team. A fractious team, at times. But without her, he does not become the artist [he was] and certainly doesn’t achieve the success.”

Born in Nyack, New York, a Hudson River town about 15 miles north of New York City, Hopper was encouraged artistically by his parents from early on. Later, during his six years at the New York School of Art and Design (now the Parsons School of Design), he studied with celebrated artists William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri.

In the early 1900s, he made three trips to Paris, where he stayed in a church mission and largely ignored the city’s vibrant artistic avant-garde. But he did engage in a largely unrequited 10-year romance with Alta Hilsdale, an affair that was revealed in a recently discovered cache of letters.

Although he created a range of imagery, Hopper is best known for views of ordinary buildings and houses in cities and small towns, including the Cape Cod village of Truro, where the Hoppers had a second residence. Sometimes, these scenes are devoid of people, and in other cases, they depict just one or two solitary figures.

Time stands still in Hopper’s quiet, detached and introspective works. He largely ignored the jutting skyscrapers, social unrest and other bustling changes around him. “His vision was apart from the world,” Adam Weinberg, former director of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, says in the film.

The filmmakers also make a point of the visual impact of movies on Hopper, who frequently went to the cinema, and, conversely, the influence of his paintings on certain directors like Alfred Hitchcock. Hopper’s “House by the Railroad” (1925), for example, has an uncanny resemblance to the house on the hill above the motel in “Psycho.”

The documentary, which runs a little more than 50 minutes, conveys Hopper’s life in a straightforward and unfussy manner, foregoing a narrator and using primarily the voices of curators and art historians to tell his story.

Along the way are invaluable clips from radio recordings and two archival television interviews that Hopper did as well as readings of letters and other writings by Hopper and his wife by noted actors J.K. Simmons and Christine Baranski.

Adding to the documentary’s affect is its gently jazzy, subtly nostalgic score, sometimes just the voice of a solitary piano, by composer Simon Farmer, who has worked as a sound mixer and recordist for more than 70 movies.

Not surprising, the first Hopper image shown is “Nighthawks,” and it gets its own small section later on. “People just love it because there are so many things that just don’t add up,” says Carol Troyen, a curator emeritus at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, in the film. “And the longer you look, the more puzzling it becomes.”

After Jan. 2, “Hopper: An American Love Story” will repeat at 1 a.m. Jan. 4 on Channel 11 and stream at schedule.wttw.com/series/136/American-Masters and on the PBS app.