COMEDY fans are preparing themselves for the post-Covid return of the huge jamboree of humour that is the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. As they do so, stand-up comedy is embroiled in a so-called “culture war” between “woke” comedians (who believe that comedy carries some kind of socio-political responsibility) and “anti-woke” acts (who, broadly, think no subject is off-limits for comedy).

However, as the good book tells us, “there is nothing new under the sun”. The current debate over “wokeness” is, in many ways, a re-run of the tussle over “alternative comedy” and “political correctness” in the 1980s.

Alternative comedy was a reaction against the right-wing humour that had predominated hitherto (in which acts like Bernard Manning and Jim Davidson had dealt, to a very large extent, in racism, sexism, homophobia and other bigotries). The new, progressive movement in comedy gave us such names as Alexei Sayle, Ben Elton, Dawn French and Jennifer Saunders, the late Rik Mayall and Adrian Edmondson.

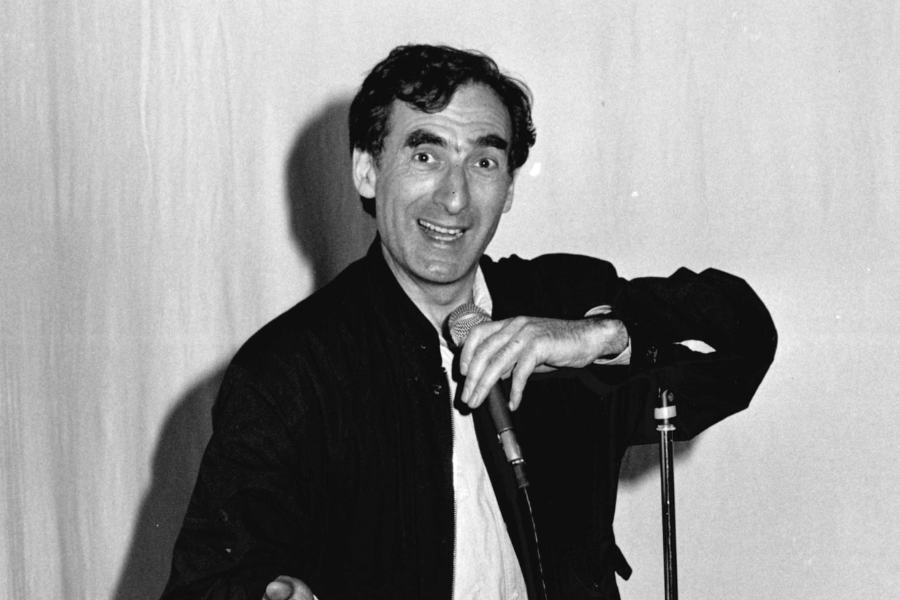

It also produced Arnold Brown, who is considered by many to be the father of alternative comedy. Raised in the Jewish community in Govanhill, on the southside of Glasgow, Brown was 42 before his career in stand-up comedy got going.

Since then he has become known as “the comedian’s comedian” (although he insists, with typical, self-deprecating wit, that it has always been his ambition to be “the bank manager’s comedian”).

Prior to his breakthrough in the 1980s, he had been an accountant. He remembers expressing his humour through cartooning and, later, writing sketches for the BBC, which was, he says, an “antidote” to accountancy.

The young Brown’s cartooning included a strip he created with a friend for the Jewish Echo newspaper in the 1950s. Titled Sammy the Shammas (“shammas” being the Hebrew and Yiddish word for a beadle or sexton of a synagogue), it followed the life of the titular character.

He remembers one Sammy cartoon in particular. The character is, the comedian tells me, “on a ladder. He is replacing the ‘exit’ sign with one that reads ‘exodus’”.

This excellent Jewish joke, created when Brown was just 20, was a harbinger of the clever, sometimes bleak, and brilliantly sharp comedy that would become his stock-in-trade as a stand-up.

The comedian remembers the early days at the Comedy Store in London. Initially, he wasn’t paid for his stand-up routines.

It took Keith Allen – a brilliant comedy pioneer who would become well-known as a member of the team that created the Comic Strip films for Channel 4 – to secure Brown’s first fee. “Keith badgered the Comedy Store people to give me £10,” the comedian recalls, with a laugh.

From there, Brown was invited by Peter Richardson (who would also become a stalwart of the Channel 4 film series) to join a group of comedians who were taking up residence at Raymond’s Revue Bar (home of the notorious strip club). The new comedy venue was called, inevitably enough, the Comic Strip.

“On one side, was the box-office for the Comic Strip,” the Glaswegian recalls, “and on the other side was the queue for the striptease punters.” This set-up was ripe for comedy. Brown duly obliged.

“One of my jokes was,” he recollects, “‘as we sit here laughing at my joke’, note no plural, ‘next door, in Raymond’s Revue Bar, 192 Japanese businessmen are lusting over our women, and you’re sitting here doing nothing about it.”

A complex joke that turns racist and sexist comedy upside down, this gag is typical of Brown’s unerring ability to create tension in an audience by challenging expectations.

I had the good fortune to experience this first-hand more than 20 years ago in New York. Brown was one of the acts in a showcase of Scottish culture which was being staged in Manhattan in conjunction with the Tartan Day parade.

As so often, the comedian made his Jewishness known early in the set. “I’m of the Jewish persuasion,” he said, before adding, “I can’t quite remember who persuaded me to be Jewish.”

As he got towards the end of the set, he created some confusion among an audience who were not accustomed to hearing Jewish comedians make jokes that were in any way critical of the State of Israel.

“When I watched the news on BBC TV, I was puzzled as to why the Jewish settlers on the West Bank always seemed to have American accents,” he said. “Now that I have come to New York, I think I understand. They had to move out because the rents in Manhattan are so incredibly expensive.”

Jokes like that have earned Brown great respect among his fellow comedians. Indeed, in 2014, he received the first ever lifetime achievement gong at the Scottish Comedy Awards (which he describes, of course, as “the Scottish OBE of comedy”).

Brown agrees with fellow comedian Jerry Sadowitz that Jewish Glaswegians have had “a double dose of gallows humour”. It is, he observes, “the old cliche of the outsiders making a joke at their expense, before someone else does.”

The comedian has often told London audiences: “I’m Scottish and Jewish. That’s two racial stereotypes for the price of one. Perhaps the best value in the West End tonight … perhaps not.”

Unsurprisingly, where Glasgow humour is concerned, the comedian talks very warmly of Billy Connolly. As to the younger generation, he has, he says, “an incredible admiration for Kevin Bridges (above)”.

“I saw him at his first Edinburgh show. I was blown away,” Brown says, “he was so young and already a perfectly formed talent.”

He remembers, in particular, Bridges’s line about a government initiative to help children in deprived areas, such as Castlemilk in Glasgow, through a music programme in schools. Bridges wasn’t sure, he said, that inequality could be addressed by giving kids a glockenspiel. The gag was delivered, Brown remembers, “with all the panache and social accuracy of Victoria Wood”.

BROWN’S admiration of Bridges doesn’t extend to the deliberately offensive humour of Jimmy Carr’s supposed “joke” about the mass murder of Roma people by the Nazis (which, Carr said, was one of the “positives” of the Holocaust). Likewise Ricky Gervais’s supposed “gags” at the expense of oppressed and marginalised groups in society.

“Stand-ups like Ricky Gervais and Jimmy Carr seem to me to be more concerned with provoking controversy than anything else,” Brown says. “Goading the ‘woke’ brigade is the main aim, but, ultimately, it doesn’t ring true.”

After he heard Carr’s material about Roma people, Brown jokes, “my idea of ‘Comic Relief’ is switching him off on TV”.

The hollow controversialising of Carr contrasts with the white-knuckle ride that is the comedy of Sadowitz, says Brown. His fellow Glaswegian is, Brown says, “the real thing” when it comes to humour that is controversial, but has irony and substance.

At the heart of Brown’s comedy is, of course, Jewish humour, which often relates, he says, to the Talmud (the central text of rabbinical teaching and law within Judaism). This involves examining an issue from many different angles and perspectives, “almost taking it inside-out”.

The best practitioner of this “Talmudic” humour is, says Brown, the New York Jewish comedian Jerry Seinfeld. Indeed, the Glaswegian’s comedy heroes include a number of New York Jewish figures, such as Mel Brooks and, Brown’s absolute favourite comedian, Woody Allen.

The maker of such films as Hannah and Her Sisters and Manhattan is the creator of “very dark humour”, the comedian says. One of his favourite gags of Allen’s is: “I got this watch from my grandfather on his death-bed … he sold it to me.”

I suggest that Brown shares with Allen an ability to deal in very serious subject matter – not least the Nazi Holocaust – with a great levity and lightness of touch. As if to prove my point, he remembers one of his jokes in that vein.

“People ask me about the Jewish contribution to civilisation. I tell them, ‘we’ve given already’.”