“You would struggle to find an elite rider who doesn’t have self-sabotaging behaviours,” says 23-year-old Ribble Rebellion rider Joe Laverick, who has witnessed many fellow riders derailing themselves with counterproductive decisions and habits. As a sports psychologist, I’m not at all surprised by this.

Whether we are riding for fun or to pay the rent, cycling can sometimes feel psychologically threatening – and threat induces self-sabotage. Because we connect cycling with our identity, the risk is that our self-worth is measured in results, speeds and watts, with an accompanying fear that if these metrics don’t live up to our self-imposed standard, we are failing. Worse still, we’re liable to worry that others are judging us for these metrics or that we’re wasting our time, putting in effort for no gain. As a result, our threat system kicks into action, with both physical and psychological consequences.

Physically, when we feel under threat, two chemicals, adrenaline and cortisol, flood the body, causing a feeling of sickness or butterflies, speeding heart rate, faster breathing, tight muscles and even impaired peripheral vision. This makes it more difficult to perform effectively in a race.

Psychologically, when our brain feels under threat, our internal commentary connives to keep us in our comfort zone; the inner voice berates us, pushing us towards self-sabotaging behaviours under the guise of self-protection. So how can you fight back against this inner critic? Here, we look at nine of the most common self-sabotaging behaviours so you can spot yours and nip them in the bud.

1) Sneaking in extra training: ‘An extra couple of reps will put me ahead’

So many sporting memes celebrate the art of doing a little bit extra, but sneaking in more training can cause burnout and see your form diving into the bin. British racer Matthew Holmes, who rode for Lotto-Soudal until last year, has recognised this trait in himself.

“The world I was in previously saw everyone fuelled by anxiety with a fear of failure, where everyone overtrains, gets chronic fatigue and ends up breaking themselves. I’m now training less to go faster.”

How to handle: Put honesty at the heart of your communication with your loved ones, team-mates and coach. They are best placed to spot when you are overdoing it, and being upfront about fears makes it more likely you will recognise it too.

2) Underselling yourself: ‘I’m not good enough to race here’

Downplaying your abilities or being pessimistic about your race prospects is something we do to try to protect our ego. What better way to manage your expectations than by pretending you are not good enough to warrant having any. Agata Woznicka, sports director and data analyst at DAS-Hutchinson-Brother UK, the women’s UCI Continental team, notices riders underestimating their own abilities. “They may even give away the leadership role to someone else who they think has a higher chance of winning,” she says.

How to handle: Other people have the power to boost our confidence, so speak to your team-mates and coach. Woznicka uses the pre-race pep talk to remind riders of their strengths. “I don’t want them to just feel they belong,” she says. “I want them to know they belong. Everyone is equal on the start line and I want them to know we have faith in their abilities, even if sometimes they don’t.”

3) Drawing unfavourable comparisons: ‘I’m not in their league’

The phrase ‘comparison is the thief of joy’ is spot-on, especially in cycling where there are so many different metrics you can use to compare yourself to others. When we lean too heavily on comparisons, we fixate on others and use their successes as a big stick to beat ourselves up with. Woznicka has observed this too. “The riders put a lot of pressure on themselves to perform because they are hoping to join a UCI professional team. When we compete against the top riders, they might feel they need to give way.”

How to handle: Focusing on your own competencies will boost motivation and confidence. Reflect on the skills or wattages you want to be able to master, write them down and work backwards so you can gently stretch your comfort zone.

4) Putting it off: ‘I’ll just do this first...’

If you get up, put your kit on and then find a million reasons why you shouldn’t ride right now, your self-sabotaging trait is procrastination. Before you know it, another task has taken precedence or you’ve missed your window of available training time without having turned a pedal – and you feel really guilty. It is probably the most common self-sabotaging behaviour. Meg Smith is the lead cycling coach at TMR coaching and says the riders who procrastinate the most are those who are not working towards a specific goal. “Often, if riders perceive training sessions to be too hard, they tend to reshuffle their schedules, and these moved sessions tend not to get completed.”

How to handle: Dr Sam Wood, a sports psychologist who lectures at Manchester Metropolitan University’s Institute of Sport, offers this advice: “Split the week into hard (red), medium (amber), and easy (yellow) intensity training days so you can relax on the easier days and plan for the harder ones, putting in fewer other difficult things on those days.”

5) Lowering the stakes: ‘I’m only racing for fun’

Ross Shand, a chartered sports and exercise psychologist at Leeds Beckett University, believes that there is one personality trait responsible for many of the self-sabotaging behaviours featured here.

“Those with strong perfectionistic characteristics who hold rigid beliefs about performance expectations, the judgements others make of them and the personal consequences of poor performance, are liable to self-sabotage,” he says. “Such thoughts and beliefs can lead athletes to experience high levels of stress and anxiety, leading them to experience a fear of failure where they avoid situations where success isn’t guaranteed.”

Shand suggests the following four ways to reduce the impact of perfectionism:

1) Have a clear plan and stick to it.

2) Change your language from ‘I must’, ‘I have to’, ‘I need to’ to ‘I want to’, ‘I can’, ‘I choose to’.

3) Reflect post-race: ask what went well and why; what could have been better and how.

4) Expose yourself to challenging situations, reflect on the outcomes and ask yourself what you learnt.

We can all agree that cycling should be fun, but if we want to improve our fitness, we need to endure uncomfortable levels of effort. Similarly in a race, if you want to do well, it is going to hurt. When you get close to race day and start using the ‘it’s just for fun’ justification, you might be making a self-sabotaging excuse just in case you don’t do as well as you would like. Coach Meg Smith says: “I’ve noticed that if a rider has set a goal for a particular race, and their legs, head or heart haven’t shown up, they tend to downplay the initial importance they had placed on the event.”

How to handle: Bite the bullet and set firm goals. Start with the outcome goal (not within your control but gets you excited), think about the performances you would need to pull off to achieve that outcome and then work back from those performances, setting in train the processes needed to achieve it. At the end of each week, look back over your training, note down the processes you followed and highlight the session you are proudest of having mastered.

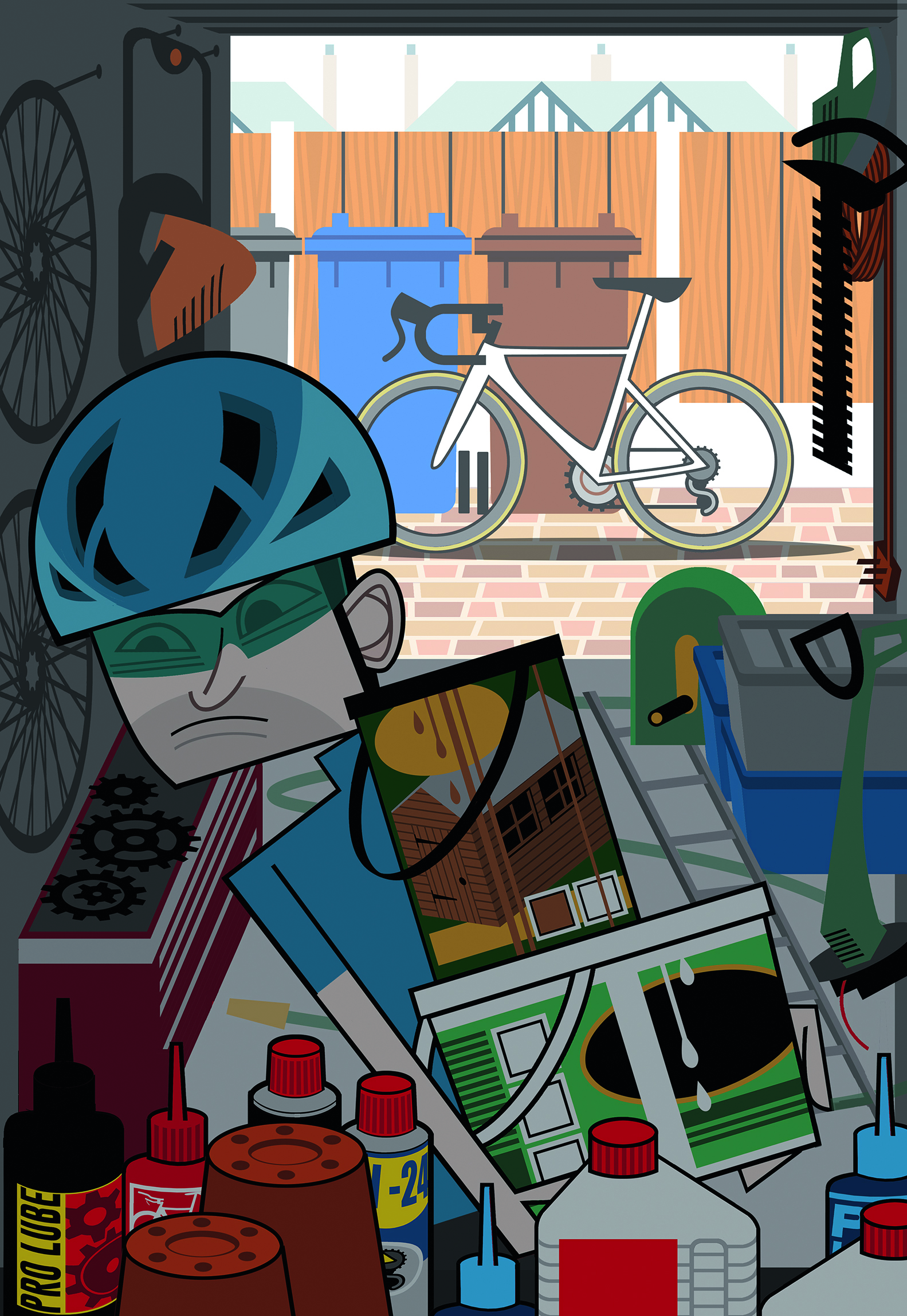

6) Busy in a bad way: ‘Sorting out the garage took so long so I ran out of time'

This is where you replace the difficult, scary thing you should be doing (say, a tough turbo) with another task that could have waited. This is known as procrastivity, a fairly new concept in sports psychology – but a commonly observed trait among cyclists. Unlike procrastination, we put off the tougher, more valuable thing not by doing nothing but by choosing a less formidable task. The cause is a lack of confidence, believes Smith. “The rider chooses to do something else because they fear failing to complete it – but often this scuppers the initial objective.”

How to handle: Coin theory is a helpful concept to employ here. Imagine that each day you get 100 coins of energy to spend. Many of your coins will be spent on the essentials of living – work, caring responsibilities, etc – so figure out the ‘cost’ of these and then see how many coins you have left. Look at your weekly cycling sessions and allocate coins to these too. Then consider where those sessions will fit into your schedule so you never ‘overspend’ and go into deficit.

7) Obsessing over results: ‘If I can’t win points, what is the point?’

The more a rider focuses on the outcomes of a race, the higher the chance their threat system will kick in and cause psychological chaos. Our minds love to predict potential outcomes – an instinct to keep us safe – and if we feel we need to ‘win’ or ‘podium’, the chance of not doing so is interpreted as a risk, which activates threat mode. Sports director Woznicka says: “Riders think that results are what speaks for their quality, yet in truth what we look at is their ability to support as a domestique or as a fearless lead-out woman. This pressure for results hinders their performance.”

How to handle: When we get too focused on results and outcomes, psychologist Dr Wood suggests delving into our values. “Sharpening a focus on the rider’s values – discipline, mastery, growth – helps identify the desired behaviours, separate from outcomes. A rider can commit 100% to demonstrating their values, even if they can’t achieve the outcome they’ve set.”

8) Racing too much: 'I can race myself into fitness'

Seventy-nine days was the average number of race days for the top male pros in 2023, and 50 for the pro women. Even for amateurs, it’s possible to race practically every week all year round, throwing in midweek crit or TTs, and even racing both days at the weekend. The more races you do, the less pressure there is to do well at each and every one. Laverick recognises this tendency in himself. “My personal self-sabotage is trying to do too much. I get my confidence from training well and preparing well, but last I year got carried away and took on more races than I should have and feel burnt-out now. Next year I will enter fewer races and prepare more strategically.”

How to handle: Follow Laverick’s example and analyse your racing season. Strip out the filler races, accepting that having fewer races on the calendar raises the stakes and may increase fear – but that you have to do that to prepare and race at your best.

9) Winging it: 'I should have trained but...'

Psychologist Dr Sam Wood says grounding exercises can help you calm negative thinking.

“Work on engaging your senses,” says Wood. “This pauses the negative thinking and allows you to refocus on what’s important.” Here are two to try: the Senses Ladder and Panoramic views.

Senses ladder: You use all five senses to pull you away from outcome ruminations and back to the present moment. Look around you and list: Five things you can see, four things you can feel, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, one thing you can taste.

Panoramic views: To open up your peripheral vision (which is deprioritised when we feel under threat), slowly walk round in a circle as if you are taking a panoramic photo on your phone camera. This helps remind your brain you are in a safe place and there is nothing genuinely scary behind you.

Finally, when we really feel under pressure (self-imposed or not), we’re liable to underprepare, telling ourselves we’ll ‘wing it’. This is a way of sidestepping responsibility, giving us a get-out clause, removing pressure and expectation. The problem is, you are likely to spend the race beating yourself up for the fact that you could have done better if only you had prepared properly.

How to handle: Remember the six Ps: Proper Preparation Prevents Piss Poor Performance. First, determine the basic minimum level of preparation needed. It might be a certain FTP number, an average speed on your local loop, or just training three times a week for two months – we all know deep down what ‘necessary fitness’ means to us. Drawing this line in the sand prevents us from starting a race in a truly unprepared state.

Recognising and countering these nine behaviours will elevate your chances of success on the bike. Whether you are overdoing it or, at the other extreme, hiding away from efforts; whether you are downplaying your ability or finding anything else to do in slots when you know you ought to be training, it’s time to stop self- sabotaging. And that starts with honest reflection. Identify your self-sabotaging behaviours and empower yourself to get back on track. A new outlook starts here: no more letting your threat system hinder your progress.