It’s time to celebrate the polysynth! Let’s be clear, that pretty much encompasses every synth you use on your computer. What we once called a polysynth is essentially any synth where you can play more than a single note simultaneously.

Over the coming days, we’re going to be celebrating where these synths came from. And in doing so, we’re going to learn more about how to use them, how to get more out of your regular favourites, and also point out some of the best alternatives out there. We're also going to compare some hardware polysynths with their software equivalents.

The polysynth revolution is a huge subject to take on with one feature, so we’ve broken it down into concise – and in some cases, not so concise – chunks that will be spread across a series of articles. We’ve tackled the history of the analogue synth, from its mono beginning, through becoming poly, to turning digital, and how they led to the synths we use today. This will give you a short and sweet context on the innovations that ultimately led to the development of your favourite plugins.

Then, we'll be taking a look at another kind of synth, the synth workstation (aka, the ROMpler). We explore how it came to be, inevitably with some overlap with the analogue evolution. And just like the analogue synth before it, this led to a very different kind of software polysynth: the workstation ROMpler.

With both of these synth types now in hand, we'll be looking at six of the best of each – classic vintage synth emulations and modern day software ROMplers – before taking you on several guided tours on how to get the best from each type. There are classic techniques, new ways to make the most of polysynth power, and step-by-step tutorials to achieve famous sounds.

We then take a look to the future (and, actually, the present) as well as a few ways that hardware and software synthesizers are no longer sitting on either side of a fence lobbing stones at one another, but actually linking up, sharing presets and more. It’s a glimpse at a sweeter, more hybrid future, one where perhaps the definitions of hardware and software are blurred.

We then tackle the thorny question of which is the best software polysynth in 2024. And with six absolute blinders included from our tests from the last 12 months, there’s plenty to choose from, and a lot of variety on offer.

Finally, and at odds with what we just said about blurring definitions between hardware and software synths, we’re going to set three hardware and software polysynths against one another.

Or rather, you are. We’re going to take three classic synths, record some similar(ish) sounds, upload them and you can select the best.

But for now, let's turn our attention to the history of the software polysynth.

The rise of the software polysynth

Can you believe that there was a time in history when you could only play one synth note at a time? Here’s how those notes increased, and how we got where we are today in the polysynth world...

Of course, almost all modern software synths are polysynths at heart, simply because computer processing is now up to speed to deliver as many notes as you can physically play for any plugin you load up. However, you can trace a lot of our current synth favourites – most in fact – back to a time when we weren’t as spoilt as we are now. A period when you could only play one note on any synth at a time. And they were glorious times.

The monosynth, i.e. any synth that can only play one note at any one time, was first developed in the ’60s/early ’70s. Yes, there are versions of the synthesiser that go back many more years, but we’re talking about machines with a keyboard where you could play a melody. It was the Minimoog, released in 1970, that history will recall as the first ever synth.

Synths stayed mono for a few years, while companies like Roland, ARP, Yamaha, Korg, and other names you’ll know from the synth world today, released machines in the early 1970s. The problem was that they still only played one note at a time.

Polyphonic dawn

In the mid ’70s, machines from the likes of Oberheim increased the number of voices by effectively adding modules together; rather like just putting two monosynths together to play two notes. Yamaha had more success with the CS-80 (eight voices) and the GX-1 (more of an organ with loads of keyboards but 18 voices). These were big machines though, and not exactly something the keyboard players of the time enjoyed lugging from gig to gig.

In 1978, the Prophet-5 came out: with five notes of polyphony and the ability to save and recall sounds (all within a single, more portable keyboard), it was a much more practical solution. And it was successful because of that.

This was a big moment in a polyphony race that has lasted to this day – even the soft synths we use now have the number of notes of polyphony quoted as an important spec. Now, of course, we want our synths to max out when our processors do, so the sky is the limit.

Back then, the big aim was to get to a mere 10 notes of polyphony, the maximum number of notes that most humans could physically play at one time. Dave Smith and John Bowen, who had invented the Prophet-5 had the ingenious solution of literally sitting two Prophet-5s on top of one another and calling it a Prophet-10. Easy!

Other companies who had joined the race developed machines that gradually increased the number of notes. You’ll have realised by now that synth manufacturers would put a heavy polyphonic clue in the name of each synth. The Roland Jupiter-8 had eight notes, and its cousins in the Juno range had six voices (yes, there was a ‘6’ in each of their names).

The digital age

Throughout the first half of the 1980s, polyphony crept up and up, but it received a larger boost with digital synths like the Yamaha DX7 and Roland D-50 which could each deliver 16 notes at a time. But, as we shall see, digital synths brought their own sets of requirements as they morphed into monster workstation ROMplers via multi-timbrality, and these would push polyphony needs up further.

However, both of these digital workstation synths and the analogue machines that we discussed earlier can be seen to have shaped the synth plugins we use today, as well as how we use them. We now have two very distinct software polysynths and two use scenarios. The first is the standard synth plugin, which you might use on multiple channels to create songs, very much as you would a hardware polysynth from the ’70s and ’80s.

Then there’s the workstation/ROMpler approach. This is where you can use a plugin like UVI Falcon or Steinberg Halion on one track to do everything – very much like a 1990s/2000s workstation.

Machines increased the number of voices by effectively adding modules together

That said, there’s actually a very good argument to say that it was more the original analogue hardware polysynths from the 1970s and ’80s that should really be given the praise for the software synth revolution we enjoy today. Let’s explain…

During the 1990s people had largely turned away from analogue to use all-new digital synths, but by the end of the decade, they realised how bland and difficult to use these early software pioneers could be, so wanted analogue back. Synth users are so contrarian.

It was the hands-on control and analogue sound that people were demanding. To cater to that hunger, it was the analogue machines that the software developers turned to when they started really emulating hardware synths. And after those very ‘analogue’ early VA synths, we are now using all sorts of polyphonic softsynths that spawned from them. Some, arguably, surpass their original hardware, at least in terms of what your computer can make them do.

However you see the history of polyphonic synths, there is no doubt that it has led to a heck of a lot of power under our mouse pointer.

Are softsynths now superior?

So, in our view – is it hardware or software that comes out on top? Perhaps the most beneficial result is to explore how you might use both to create real polysynth harmony…

As seasoned music technology journalists, we’ve been very much writing about the separate worlds of hardware and software polysynths over the last two decades. They’ve long been very different beasts in terms of cost, with hardware, and, especially vintage hardware synths being extraordinarily expensive.

Software has – with one or two exceptions – always been the cheaper and more practical alternative

Software has – with one or two exceptions – always been the cheaper and more practical alternative. The ‘fight’ between the two types of synth has been rumbling for a while, but might we be approaching an amicable resolution? 2024 looks set to be the year when the barriers (and points of difference) between the the two fall.

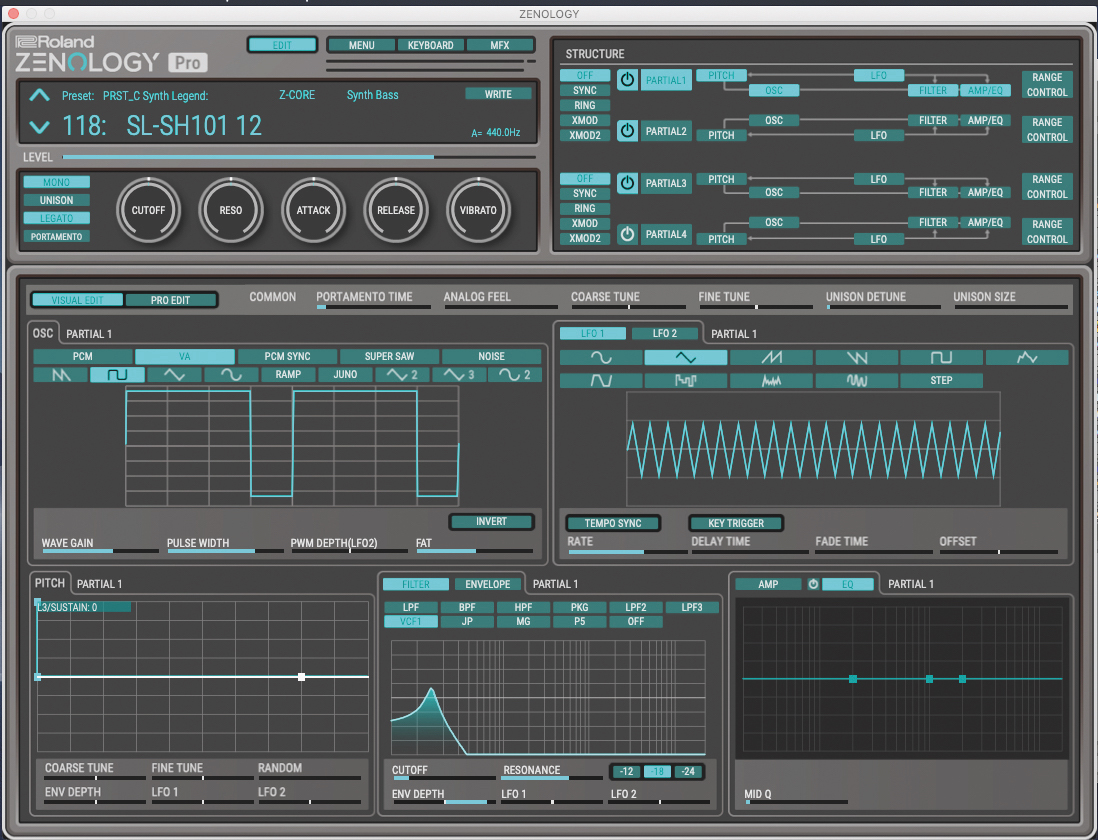

Roland Zen-Core is perhaps the biggest example of this. It’s a complete hardware/software ecosphere where you can load classic and modern synth sounds into hardware like the Roland Fantom or Jupiter-X, and take it anywhere, even using it as a plugin in your DAW.

On a simpler level, we’re now getting hardware synths released with software counterparts thrown in for good measure; the Arturia MiniFreak is a prime example. You can buy this amazing polysynth as software, or buy it in hardware. Do the latter and Arturia throw the software version in for free.

ZEN-Core goes hardcore: five classic synths for your DAW or Roland hardware

While this is not completely new (we recall Novation throwing in the software version of its Bass Station in with hardware many years ago) it is the first time the match has been so integrated. These two different versions can be used separately, but together, it’s a joy!

In MiniFreak’s case, for example, the software is opened up and gives you more hands-on access to different tabs, pages and features, but the hardware gives you the tactile control you (might) yearn for. Of course, a hardware MIDI controller can give you the same effect, but the marriage here is perfect; no messing around with assignments, just synthesise, create and make tunes.

The interesting thing here is that the two synths sound identical as they’re both digital and use the same algorithms, so you might think “well, I’ll just use the software then”. But the price is not that great between them – the software costs around €150 and the hardware around €490 – thanks largely to the fact that hardware processing costs have fallen.

This new generation sounds a lot better and have far more hands-on controls than the not-so-easy-to-master digital synths of the 1990s

In fact, there has been a recent resurgence in hardware polysynths because those prices have fallen, not to mention that this new generation sounds a lot better and have far more hands-on controls than the not-so-easy-to-master digital synths of the 1990s. This means that we’ll probably see this marriage of the two synth types extend to many other brands as more digital polysynths come out.

And then, of course, there are the companies like Native Instruments who are exploring the opposite direction, where keyboards integrate deeper with software. We’ll likely see its latest ‘Kontrol’lers become more independent from the software they master, effectively becoming hardware workstations.

Either way, the days of us simply comparing hardware synths with software synths are probably numbered. And who wins? All of us.

Keep an eye on MusicRadar over the coming days and join us as the Great Synth Showdown continues.