Aquaman was a movie that worked in spite of itself. James Wan’s 2018 superhero epic occupied its own weird, wild corner of the DC Extended Universe. It was a glimpse at what this cinematic universe could’ve been — a place for directors to realize their inspired vision of larger-than-life gods on the big screen. And in Wan’s case, that vision was of a surfer bro thrust into an Arthurian quest to save the world. It was juvenile. It was campy. It was a little creepy. But most of all, it was unique.

Four years later, the DCEU is on its last legs, and Jason Momoa’s Aquaman is tasked with turning out the lights. But like Liza Minelli trying to turn off a lamp, he doesn’t take the most straightforward route to the end. Instead, Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom — much like the first film — is a wild mishmash of tone and plot that jettisons the final DCEU film over the finish line in a show of brute strength, pulpy misadventures, and oddly disarming charm. It’s a mess of a movie, but gosh darn is it a fun mess.

Several years after the events of the first film, Arthur Curry has uncomfortably settled into his new life as King of Atlantis. His goal to unite the underwater world and the surface world is stalled by geopolitics and prejudice — as well as by his penchant for slipping out to battle pirates. Arthur’s one beacon is his baby son, whom he happily raises on shore alongside Mera (Amber Heard) and his father (Temuera Morrison).

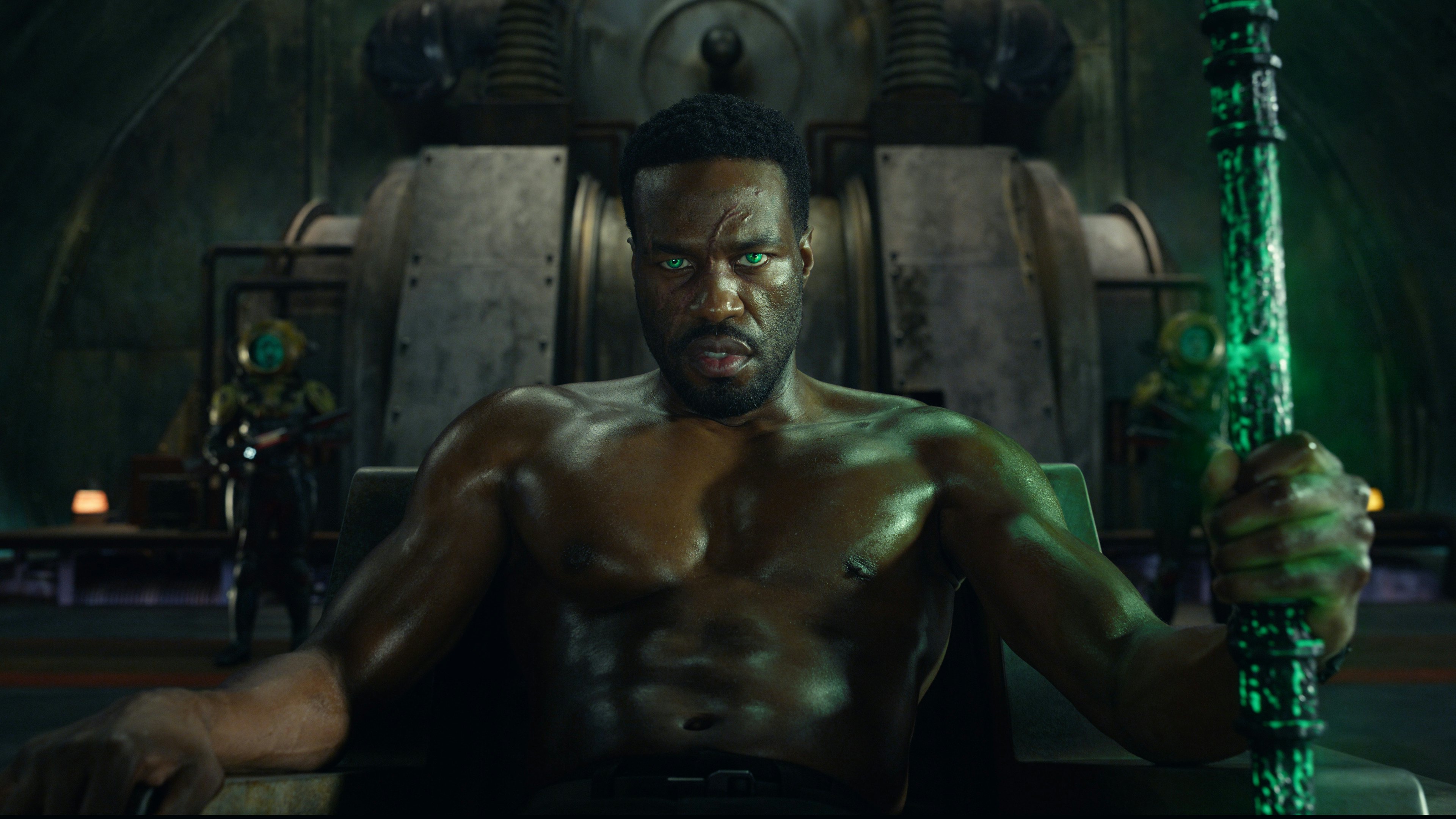

However, Aquaman’s fragile harmony is interrupted by the re-emergence of David Kane, aka Black Manta (Yahya Abdul-Mateen), the high-seas mercenary who is still working on that plan to get vengeance against Aquaman for murdering his father. But Black Manta’s latest scheme, in which his discovery of a lost Atlantean kingdom results in him getting possessed by the DCEU version of Sauron, proves to be one of the world-ending kind. With the rapidly warming climate putting Atlanteans on the verge of attacking the surface-dwellers again, Arthur is forced to team up with his treacherous brother Orm (Patrick Wilson) to stop Black Manta from unleashing Lovecraftian hell on Earth.

Narratively and tonally, Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom is essentially like Aquaman but more. Where the first hyperactively swung between Indiana Jones-like escapades and Arthurian deep-sea quests, The Lost Kingdom takes it up a notch with its vast array of influences. At one point, it’s a Jules Verne pulp adventure juiced up on a cocktail of testosterone, adrenaline, and Guinness beer. At another, it’s a Lovecraftian horror show, expanding on Wan’s blood-curdling depiction of the Trench from the first film. And at yet another, it’s a Lord of the Rings-inspired epic populated by undead kings and skeletal warriors.

It’s with The Lost Kingdom that Wan takes his worldbuilding ambitions to the next level, delivering rich mythology and impossibly vast worlds… for Momoa’s Aquaman to just ignore. The comical dichotomy of this richly imagined world being discovered by the most unimaginative surfer bro is part of Aquaman’s dumb charm. It’s the same kind of self-effacing humor masquerading as a self-serious attitude that Wan perfected in films like Malignant. And it becomes even funnier when The Lost Kingdom finds a better straight man for Momoa in Wilson’s Orm.

Once The Lost Kingdom becomes a buddy-comedy adventure between Aquaman and Orm, the film really starts to sing. While Momoa’s bro-y performance as Aquaman — which has not much evolved since the first film — can get old fast, Wilson makes it bearable by understanding exactly the kind of wavelength that Wan is on. Wilson’s Shakespearean approach to Orm in the first film is fully realized as the camp performance it was always meant to be. He’s Orm the Ocean Master! The ocean gives him abs! He does the Naruto run! As the disgraced former King of Atlantis, Orm is a pathetic failure, but weirdly proud of it.

With this new dynamic between two ego-tripping demi-gods, the DCEU finds its surprising equivalent to Marvel’s Thor and Loki — a duo that feels like it would’ve become a staple of the franchise if Aquaman had only come out earlier (or the DCEU was planned better). It’s a shame we’ve only been gifted this pairing at this point in time, but at least we get to see Orm eat cockroaches in a bit that goes on way longer than you’d think.

Unfortunately, the delightfully barbed banter between Aquaman and Orm can only carry the film so far. David Leslie Johnson-McGoldrick’s script is overstuffed and chaotic, so full of ideas it threatens to spill over. The film becomes a slog when any kind of exposition is delivered, and becomes even more grating when Wan and Momoa try to liven it up by having Momoa deliver cheeky voiceovers lampshading every serious development. Because Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom is the Arthur and Orm show, the other characters get sidelined (apart from Morrison’s salt-of-the-earth Tom Curry and Dolph Lundgren’s imposing King Nereus). Nicole Kidman gets to spout some exposition and muse sadly over the enmity between her sons, while Park has a fun role as Black Manta’s morally-conflicted scientist grunt. But the charisma and star power that Yahya Abdul-Mateen II showed as Black Manta in the first film is wasted again, with the character spending most of the film possessed by an eldritch evil.

But the biggest sore spot of the film is how obvious it is that Amber Heard’s part has been dialed way back. Arthur might as well be a single father based on how little Mera appears in the opening montage as he tries to balance royal duties with family life. Even in Mera’s most pivotal moments, when she rescues Arthur or mounts a daring attack against Black Manta’s forces, it’s clear her dialogue and role were cut back significantly. While it was ultimately in the film’s benefit to give the spotlight to the dynamic duo of Aquaman and Orm, the film’s timid backseating of Mera undercuts its brutish charm.

While Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom can’t be described as a wholly good movie, it’s at least a fun one. Its chaotic, messy story can be somewhat forgiven when you’ve got a master visualist like James Wan who imbues a sort of mid-aughts B-movie blockbuster charm to every frame. And once the second “Born to be Wild” needle drop hits, you can’t help but get your spirits up. Sometimes, all you need is good, dumb fun. It’s a weird way to end a cinematic universe, for sure, but at least the DCEU went out with a bang.