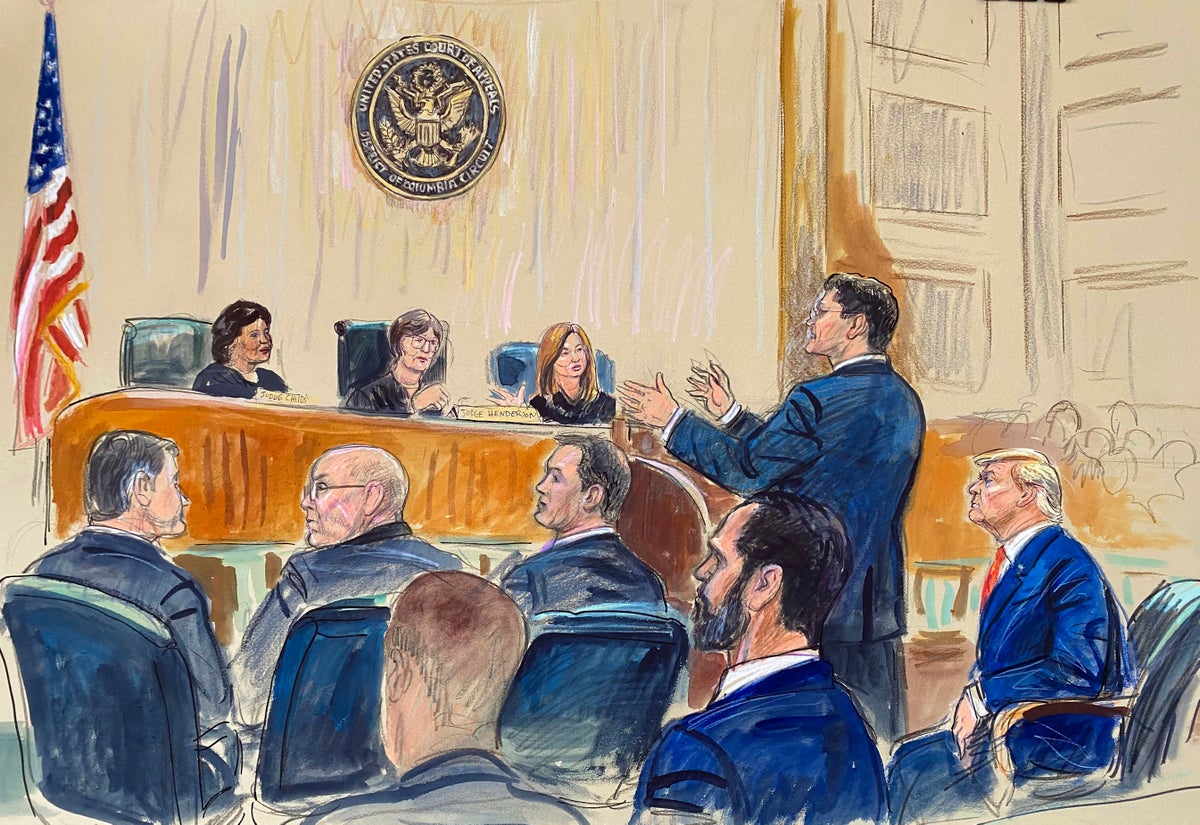

A trio of judges on the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit appeared to be sceptical of former president Donald Trump’s claim that he enjoys sweeping immunity from prosecution as an ex-chief executive during arguments in a Washington DC courtroom on Tuesday.

With Mr Trump present in the courtroom, not far from where a riotous mob of his supporters stormed the US Capitol just three years ago, all three members of the three-judge panel expressed at least some level of doubt at the arguments put forth by Mr Trump’s attorneys, who were appealing a district court judge’s decision denying him the immunity that would prevent him from being tried on charges related to his efforts to unlawfully remain in office after losing the 2020 election to President Joe Biden.

Judge Florence Pan, a 2022 appointee to the circuit court by President Joe Biden, almost immediately began a rapid-fire questioning of Trump attorney D John Sauer over his contention that presidents cannot be prosecuted absent a conviction following an impeachment trial in the Senate.

She asked Mr Sauer if, hypothetically, a president could order the killing of a rival by the US military or sell pardons and be immune from any legal consequences.

“I understand your position to be that a president is immune from criminal prosecution for any official act that he takes as president even if that action is taken for an unlawful or unconstitutional purpose, is that correct?” she said.

He replied that prosecution would only be allowed following a conviction by the Senate.

Mr Sauer also argued to the court that prosecutors’ position against immunity would allow a US Attorney in Texas to somehow prosecute Mr Biden after the end of his term for “mismanaging the border allegedly”.

His arguments appeared to receive a critical reception from the two other judges on the panel, Judge Michelle Childs and Judge Karen Henderson.

Judge Childs, a recent appointee to the court under Mr Biden who was also under consideration for the US Supreme Court seat now held by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, suggested that there has never been any presumption of post-presidency immunity for ex-presidents, citing Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon after Nixon’s resignation from the presidency.

The pardon, she said, indicated “an assumption that you could be prosecuted”.

In response, Mr Sauer argued that Nixon’s potential prosecution would have been for private conduct and attempted to distinguish that case from Mr Trump, who he claimed was being prosecuted for official actions taken to question election results.

But Judge Florence Henderson, a veteran of the court who was appointed by President George W Bush, suggested that the immunity Mr Trump’s attorneys are seeking is in conflict with the president’s basic responsibilities.

“I think it’s paradoxical to say that his constitutional duty to take care that the laws be faithfully executed allows him to violate criminal law,” she said.

The attorney appearing for Special Counsel Jack Smith’s office, James Pearce, told the panel that the government’s position is that there is no immunity for ex-presidents for any criminal acts.

“The President has a unique constitutional role [but] is not above the law,” he said. “Separation of powers principles, constitutional text, history, precedent, and other immunity doctrines all points to the conclusion that a former President enjoys no immunity from criminal prosecution”.

Mr Pearce added that at minimum, the court should not recognise any form of immunity in this case, citing the fact that Mr Trump is “alleged to have conspired to overturn the results of a presidential election”.

Asked whether the government believes the court has jurisdiction to hear the case at this stage under court precedent limiting criminal appeals before a trial has taken place, Mr Pearce told the court that the government’s interest is in “doing justice” and serving the public interest by moving quickly to a trial.

Citing arguments from Mr Trump’s attorneys who claimed that denying Mr Trump immunity would result in a glut of prosecutions of ex-presidents every time the White House changes hands from one party to another, Judge Henderson asked Mr Pearce how the court could craft an opinion that would avoid “opening the floodgates” to political prosecutions.

He replied that previous investigations of presidents, such as the long-running probe into then-president Bill Clinton in the 1990s, didn’t result in Mr Clinton being charged with any crimes.

“The fact that this investigation did doesn't reflect that we are going to see a sea change of vindictive tit-for-tat prosecutions in the future. I think it reflects the fundamentally unprecedented nature of the criminal charges here,” he said.

“Never before has there been allegations that a sitting president has, with private individuals and using the levers of power, sought to fundamentally subvert the democratic republic and the electoral system. And frankly, if that kind of fact pattern arises again, I think it would be awfully scary if there weren't some sort of mechanism by which to reach that in criminally”.

The charges against Mr Trump stem from a multi-year federal investigation into his and his allies’ efforts to subvert the outcome of the 2020 election as detailed in a 45-page indictment outlining three alleged criminal conspiracies and the obstruction of Joe Biden’s victory, culminating in a mob’s violent breach of the US Capitol.

Last month, US District Judge Tanya Chutkan rejected Mr Trump’s motion to dismiss the case on his “immunity” grounds, writing in a 48-page ruling that his four-year term “did not bestow on him the divine right of kings to evade the criminal accountability that governs his fellow citizens.”The office “does not confer a lifelong ‘get-out-of-jail-free’ pass,” nor do former presidents enjoy any special consideration after leaving office, when they are “subject to federal investigation, indictment, prosecution, conviction, and punishment for any criminal acts undertaken while in office,” according to Judge Chutkan.

Last month, the US Supreme Court declined the special counsel’s request to fast-track a review of Mr Trump’s immunity claims, letting the appeal play out as scheduled at the appellate court.

But an appeal of any outcome from Tuesday’s hearing could likely head right back to the nation’s high court, potentially causing delays and pushing the start of Mr Trump’s trial back from the 4 March start date set out last summer by Judge Chutkan.

Mr Smith’s office has warned judges and the Supreme Court that ongoing litigation could push a timeline further into the election year, opening the possibility of courts deciding whether to try Mr Trump as a president-elect.

If the appeals judges dismiss Mr Trump’s claims, his attorneys could request a re-hearing with a full panel of appellate judges or take the case to the Supreme Court.

Justices are already scheduled to consider another major constitutional question of whether he can disqualified from public office under the scope of the 14th Amendment, which prohibits anyone who has sworn an oath to uphold the Constitution and “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” from holding public office.