When the history of the tragedy of Ukraine comes to be written, the writers will be grateful for the hard work of a team led by a Canberra historian.

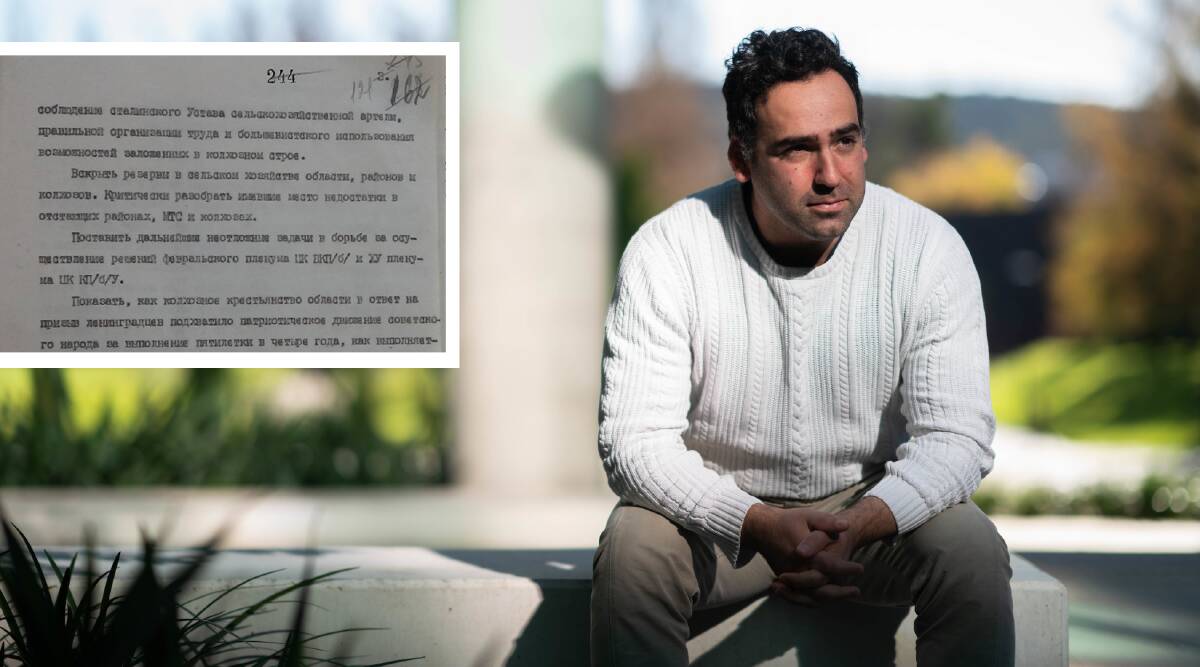

Before the war started, Dr Filip Slaveski from the ANU had been making digital copies of original documents from Soviet archives, but now some of the buildings housing those essential historical sources are targets of Russian weaponry.

As the war progresses, Canberra is becoming the back up repository for the documents. Whatever is destroyed in the original should have a digital copy at the ANU.

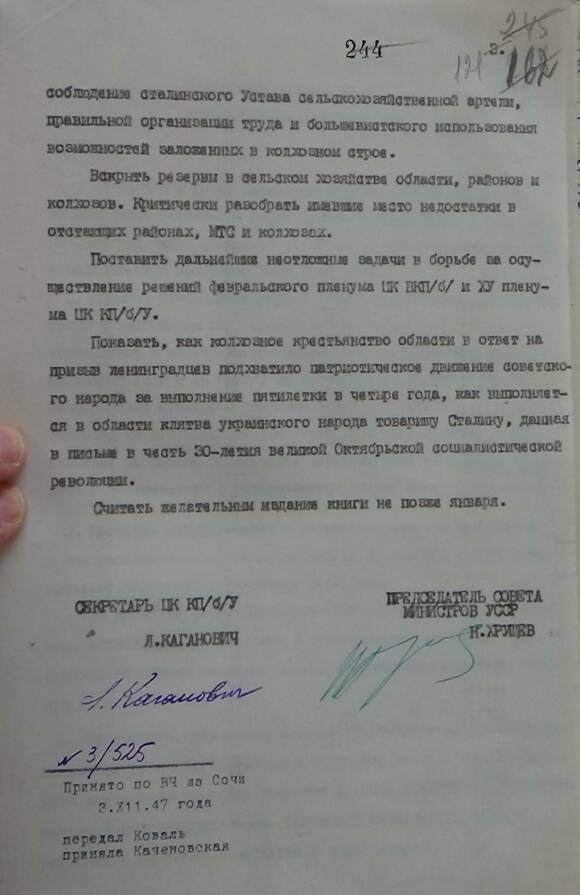

The documents which Dr Slaveski is most keen to preserve relate to the famine of 1932 and 1933.

During what Ukrainians call the Holodomor, at least a million people died of starvation after the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin drove through attempts to extract grain from Ukrainian peasants. People were terrorised and executed for not offering up wheat they simply didn't have. As mass malnutrition set in, cannibalism emerged among families whose members faced imminent death through starvation.

Ukrainians are keen for this history to be preserved because it was denied as true by the Soviet Union, and is ignored by the present-day rulers of Russia.

At the time, the West also denied the existence of famine in the Ukraine - with the exception of the Welsh journalist Gareth Jones who documented it but whose true accounts were not believed. ("Conditions are bad, but there is no famine," the New York Times correspondent, who was a Stalin apologist, wrote falsely in March 1933.)

With the fall of the Soviet Union and the creation of an independent Ukraine, the documents became available, but war now threatens them.

Some buildings are already thought to have been destroyed, not because they held the papers, but because they were targeted as military or government buildings.

"By virtue of where these things are located, they're in danger," Dr Slaveski said. "I know particularly they've been bombing intelligence agencies and the intelligence archives."

Even where buildings haven't been destroyed, he is worried that the destruction war brings (like burst pipes) will prevent the papers being preserved.

In 2021, Dr Slaveski and his team won an Australian Research Council grant to write the first comprehensive history of the famine in English.

Because the pandemic stopped them visiting Ukraine, they worked with people there and in Russia and in the former Soviet territory of Moldova to get as much as they could copied and digitised.

And then came the war and the threat to the originals.

It's not been possible to keep research in Russia going because of sanctions by the Australian government. That meant that Russian helpers could not be paid even for work to aid ANU research.

But Ukrainians work on.

"Some of my archivists refused to leave Kyiv during the invasion because they wanted to protect the archives," Dr Slaveski said.

"It's incredibly noble of them, but it's put them in real danger."