The rhythmic expansion and contraction of Antarctic sea ice is like a heartbeat.

But lately, there’s been a skip in the beat. During each of the last two summers, the ice around Antarctica has retreated farther than ever before.

And just as a change in our heartbeat affects our whole body, a change to sea ice around Antarctica affects the whole world.

Today, researchers at the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (AAPP) and the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS) have joined forces to release a science briefing for policy makers, On Thin Ice.

Together we call for rapid cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, to slow the rate of global heating. We also need to step up research in the field, to get a grip on sea-ice science before it’s too late.

The shrinking white cap on our blue planet

One of the largest seasonal cycles on Earth happens in the ocean around Antarctica. During autumn and winter the surface of the ocean freezes as sea ice advances northwards, and then in the spring the ice melts as the sunlight returns.

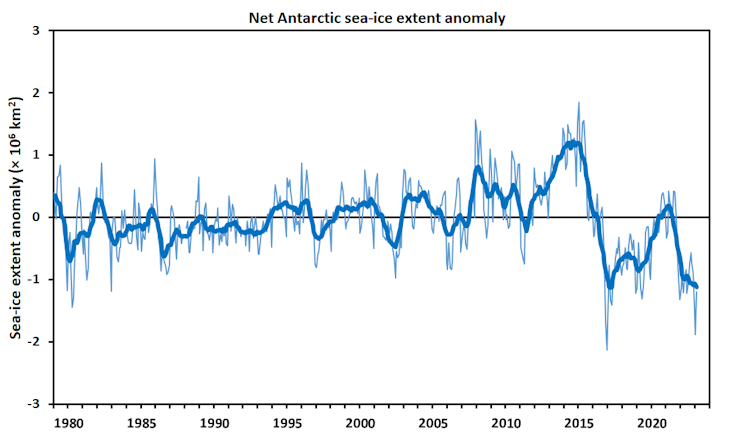

We’ve been able to measure sea ice from satellites since the late 1970s. In that time we’ve seen a regular cycle of freezing and melting. At the winter maximum, sea ice covers an area more than twice the size of Australia (roughly 20 million square kilometres), and during summer it retreats to cover less than a fifth of that area (about 3 million square km).

In 2022 the summer minimum was less than 2 million square km for the first time since satellite records began. This summer, the minimum was even lower – just 1.7 million square km.

The annual freeze pumps cold salty water down into the deep ocean abyss. The water then flows northwards. About 40% of the global ocean can be traced back to the Antarctic coastline.

By exchanging water between the surface ocean and the abyss, sea ice formation helps to sequester heat and carbon dioxide in the deep ocean. It also helps to bring long-lost nutrients back up to the surface, supporting ocean life around the world.

Not only does sea ice play a crucial role in pumping seawater across the planet, it insulates the ocean underneath. During the long days of the Antarctic summer, sunlight usually hits the bright white surface of the sea ice and is reflected back into space.

This year, there is less sea ice than normal and so the ocean, which is dark by comparison, is absorbing much more solar energy than normal. This will accelerate ocean warming and will likely impede the wintertime growth of sea ice.

Headed for stormy seas

The Southern Ocean is a stormy place; the epithets “Roaring Forties” and “Furious Fifties” are well deserved. When there is less ice, the coastline is more exposed to storms. Waves pound on coastlines and ice shelves that are normally sheltered behind a broad expanse of sea ice. This battering can lead to the collapse of ice shelves and an increase in the rate of sea level rise as ice sheets slide off the land into the ocean more rapidly.

Sea ice supports many levels of the food web. When sea ice melts it releases iron, which promotes phytoplankton growth. In the spring we see phytoplankton blooms that follow the retreating sea ice edge. If less ice forms, there will be less iron released in the spring, and less phytoplankton growth.

Read more: Smoke from the Black Summer fires created an algal bloom bigger than Australia in the Southern Ocean

Krill, the small crustaceans that provide food to whales, seals, and penguins, need sea ice. Many larger species such as penguins and seals rely on sea ice to breed. The impact of changes to the sea ice on these larger animals varies dramatically between species, but they are all intimately tied to the rhythm of ice formation and melt. Changes to the sea-ice heartbeat will disrupt the finely balanced ecosystems of the Southern Ocean.

A diagnosis for policy makers

Long term measurements show the subsurface Southern Ocean is getting warmer. This warming is caused by our greenhouse gas emissions. We don’t yet know if this ocean warming directly caused the record lows seen in recent summers, but it is a likely culprit.

As scientists in Australia and around the world work to understand these recent events, new evidence will come to light for a clearer understanding of what is causing the sea ice around Antarctica to melt.

If you noticed a change in your heartbeat, you’d likely see a doctor. Just as doctors run tests and gather information, climate scientists undertake fieldwork, gather observations, and run simulations to better understand the health of our planet.

This crucial work requires specialised icebreakers with sophisticated observational equipment, powerful computers, and high-tech satellites. International cooperation, data sharing, and government support are the only ways to provide the resources required.

After noticing the first signs of heart trouble, a doctor might recommend more exercise or switching to a low-fat diet. Maintaining the health of our planet requires the same sort of intervention – we must rapidly cut our consumption of fossil fuels and improve our scientific capabilities.

Edward Doddridge receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Australian Government.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.