Four months ago, Mayor Lori Lightfoot declared Chicago was poised for the “best economic recovery of any big city in the nation, bar none,” no matter “what the naysayers claim.”

Now, the mayor has some hard numbers to back up that bold claim, which laid the groundwork for her re-election bid.

The Certified Annual Financial Report for 2021 shows Chicago closed the books on 2021 with a total fund balance of $679.1 million, with $318.1 million of that categorized as “unassigned,” meaning it isn’t yet dedicated for a specific expense.

The audit credits two primary factors — revenue streams that had been impacted by the pandemic are starting to recover, and federal COVID relief grants were used to help cover some city expenditures.

In spite of that $319.6 million surge in those impacted revenue streams, described in the audit as “economically sensitive revenues,” the percentage of unassigned revenues “compared to expenditures” remained stable, according to the report.

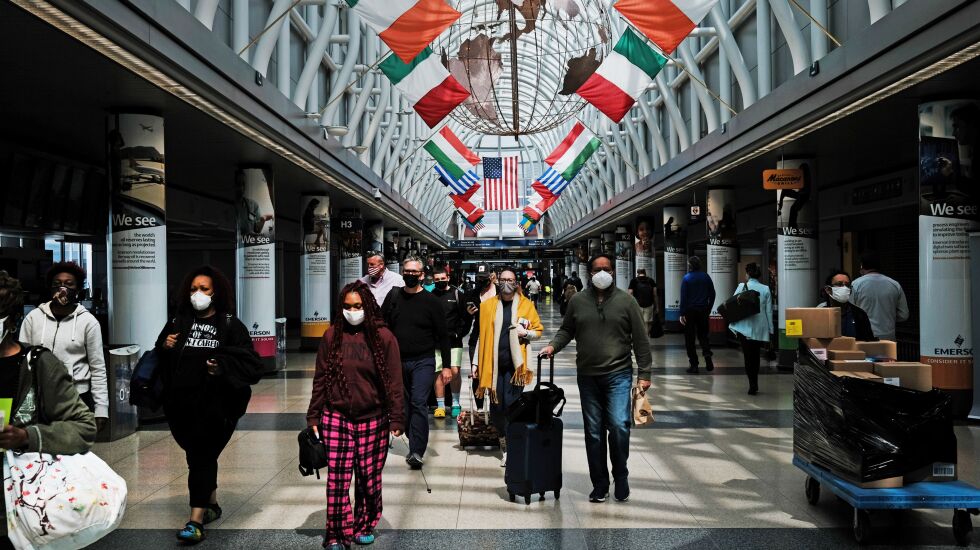

The rebound was on full display at O’Hare International Airport, where operating revenues rose by $239.5 million — 26.5%.

That was thanks to increased terminal use charges and landing fees of ($176.1 million), a $49.2 million increase in concession revenues and a $14.2 million hike in hotel revenues “as the airport started to recover from the pandemic.”

The total number of flights originating at O’Hare or connecting through the airport rose from 15.35 million in 2020 to 26.9 million last year.

In 2019 — the last year before the pandemic that number — the audit calls them “enplanements” — stood at 42.2 million. Total passengers in 2021 were just over 54 million, up from 30.8 million the year before, but a far cry from the 84.6 million in 2019.

At Midway, total operating revenues rose by $33.1 million, “primarily due to a significant increase in passenger volume, terminal rental revenues and concessions.” Total aircraft operations stood at 185,956. That’s up from 150,198 in 2020, but still way down from the 232,084 in 2019.

Lightfoot is rightfully proud of having “climbed the ramp” to actuarial funding of Chicago’s four city employee pension funds.

But the audit, by the accounting firm of Deloitte & Touche LLP, shows how desperately Chicago still needs a long-term solution to its pension crisis.

That’s even after signing off on Bally’s plan to build a $1.7 billion River West casino — and a temporary casino at Medinah Temple — which is being touted as a $200 million-a-year salvation for police and fire pensions.

The city’s total pension liability stands at $33.6 billion. That’s $700 million higher than at the close of 2019, when the pension liability rose by 5.6%.

The firefighters pension fund remains the worst off of the four, with assets to cover just 20.9% of its liabilities. That’s followed by the Municipal Employees Pension Fund (23.4%), Police (23.5%) and Laborers (45.9%).

With the mayoral election now just over six months away, Lightfoot has made virtually no long-term progress on pensions.

Early on, Lightfoot floated a plan for a state takeover of Chicago’s four city employee pension funds, only to be shot down cold by the governor.

The governor subsequently made Chicago’s pension crisis infinitely worse by ignoring the mayor’s plea to veto a bill boosting pensions for thousands of Chicago firefighters. Lightfoot had argued it would saddle beleaguered city taxpayers with perpetual property tax increases and cripple the pension fund closest to insolvency.

The mayor has also alternately touted a sales tax on services and an increased real estate transfer tax on high-end purchases as a solution to Chicago’s pension crisis, but both plans have gained no traction in Springfield.

As always, the city audit is chock-full of information about Chicago finances and the local economy. Those tidbits include:

• Total long-term obligations stand at $64.4 billion. Annual debt service rose from $688.5 million in 2012 to $1.01 billion last year.

• Chicago completed $240.3 million in infrastructure projects in 2021, including $188.3 million in street construction and resurfacing, $13.5 million in street lighting and mass transit projects and $38.5 million in bridge and viaduct reconstruction.

• O’Hare added $776.2 million in capital improvements. At Midway, it was $17.1 million.

• Total long-term obligations stood at $64.4 billion. Outstanding general obligation bonds backed by property taxes declined by nearly $1.1 billion in 2021 due to payment on those general obligation bonds and other debt and refinancing of $1.98 billion.

• Chicago Police officers made 38,400 “physical arrests” in 2021, down 26.6% from the year before and 57% percent from 2019. In 2012, there were 145,390 physical arrests.

• Chicago’s $1.6 billion property tax levy — now locked in to annual increases of 5% or the cost of living, whichever is less — nearly doubled between 2012 and 2021.

• Amazon was Chicago’s top employer in 2021, with 27,050 or 2.17 % of the city’s overall workforce. That was followed by: Advocate Aurora Health (25,9660; Northwestern Memorial Health (24,053); the University of Chicago (20,781) and Wal-Mart (18,500).

• Chicago firefighters and paramedics responded to 632,745 emergencies last year, a nearly seven percent increase from the year before. In 2016, there were 713,492 emergency fire calls.

• Average daily water consumption continued their steady decline — from 640,509 million gallons in 2020 to 595,302 million gallons in 2021. That’s a seven percent decline. Even so, gross operating revenues for 2021 rose by $24.9 million thanks largely to a $20 million increase in water rates.

In May, top mayoral aides disclosed Lightfoot’s pre-election budget included a revised, $305.7 million shortfall — $561 million below earlier estimates — thanks to hold-over federal relief funds and an improving economy.

The holdover funds were $152.4 million. The improving revenues accounted for $250 million of that revised figure.

Lightfoot’s $16.7 billion budget sailed through the Council, 35-15, thanks to an avalanche of federal stimulus funds paving the way for an unprecedented 30% increase in city spending.

Lightfoot moved up the budget process by a month to coincide with the unveiling of her plan to spend federal relief funds.

She ended up using 68% of it or $782.2 million for revenue replacement.

That freed up the city’s corporate fund to repay a $450 million line of credit used to eliminate a pandemic-induced shortfall and cancel $500 million in refinancing of city debt — sometimes called “scoop-and-toss” borrowing — that would have been necessary without the federal largesse.

Still, she managed to earmark $1.2 billion for new investments by pooling $563 million in federal money with the $660 million that represents the 2022 installment of her capital plan.

Despite the political euphoria that came from having put the budget to bed in record time, Civic Federation President Laurence Msall warned that Chicago was hardly out of the woods.

Although the city has started the long road to 90% funding of its pension funds, Msall warned then that there is still no long-term funding source from Springfield. Nor has the General Assembly heeded the Civic Federation’s call for a state constitutional amendment eliminating the pension protection clause going forward.

Msall also remained concerned about the mayor’s continued reliance on one-time revenues, the city’s mountain of debt and about her plan to refinance $1.2 billion more and use $232 million of the savings to bankroll four years of back pay for Chicago police officers.

He was equally concerned about what will happen “when the federal ARP money goes away” — particularly if the $153 million in federal relief reserved for revenue replacement in 2023 is not enough.

“What’s Plan B if the city does not recover at the aggressive and robust growth that the city is hoping for? We need to have a Plan B. Will we try to raise taxes if the economic disruption caused by the pandemic continues? Will we make structural changes? Will we be cutting?” he said.

“In likelihood, it’s going to have to be a combination of all of that. But if we don’t see a return where business travel comes back, where convention attendance [comes] back, the city is going to have a hard time meeting its debt obligations for many of the key investments that those industries support.”