In 1982, the NFL was changing, although most scribes who covered professional football were years away from recognizing what a young sportswriter already saw. This author, big and beefy and already sporting a glorious red mustache, hailed from Los Angeles and moonlighted as a backup offensive tackle on the BYU football team. He wrote the following sentence, as part of a series of freelance articles for the Provo Daily Herald:

The name of the NFL game is pass.

The kid who wrote that sentence stood 6'3", weighed around 230 pounds, accumulated zero college statistics and played only in spring games through three seasons. He majored in physical education. He counted Jim McMahon among his teammates.

This kid, with his notepad and his shoulder pads, his mustache and his pen stash, still wasn’t sure what career he wanted. “Professional athlete” seemed improbable. He found teachers—and their profession—inspiring. His father, Walter, was creative, a designer of movie sets; his mother, Elizabeth, analytical, a doctor with caring embedded in her soul. And he thought, way back then, that “writing for Sports Illustrated might be pretty cool.”

Illustration by Madison Ketcham

He did not yet realize. He saw football like a . . . coach.

Reminded before this season started of that sentence he wrote nearly 31 years ago, the author chuckles over the phone from Kansas City. Practice had just wrapped up. “I know, I know,” Andy Reid says. “That’s just kinda what it was. I didn’t know [the NFL] was gonna end up where it ended up.”

So brash with the long-ago pen. So buttoned up now, at least in public. That’s the difference between a man in charge of a possible burgeoning sports dynasty with the Chiefs and a kid hunting for a story. But one concept speaks to both worlds, which bump up against each other and sometimes intersect. Perhaps writing about sports projected or even aided Andy Reid, winner of Super Bowls, offensive innovator, Hall of Fame shoo-in. Storytelling likely made him a better coach.

Illustration by Madison Ketcham

Reid transferred from Glendale Junior College in sunny California to snowy BYU in 1978. He was not a writer, per se, but more of an intellect who doubled as a jock. Long before Andy channeled the creativity of his father, filling whiteboards with intricate play designs that resemble a human genome map, he simply followed what called to him.

But it’s not as if Reid showed up on campus and went directly to the student newspaper, begging for bylines. The Daily Herald had an idea for him.

On the football field, Reid stood on the sidelines throughout historic seasons (led by McMahon, the Cougars went 12–1 in 1980) and cheered himself hoarse through indelible victories (like their Holiday Bowl triumph over SMU that year, in which they scored four touchdowns in the fourth quarter, the last on a Hail Mary as time expired). All the while, he studied the game’s intricacies and nuances by observing up close LaVell Edwards, BYU’s respected coach, then in the ninth year of a 29-year career.

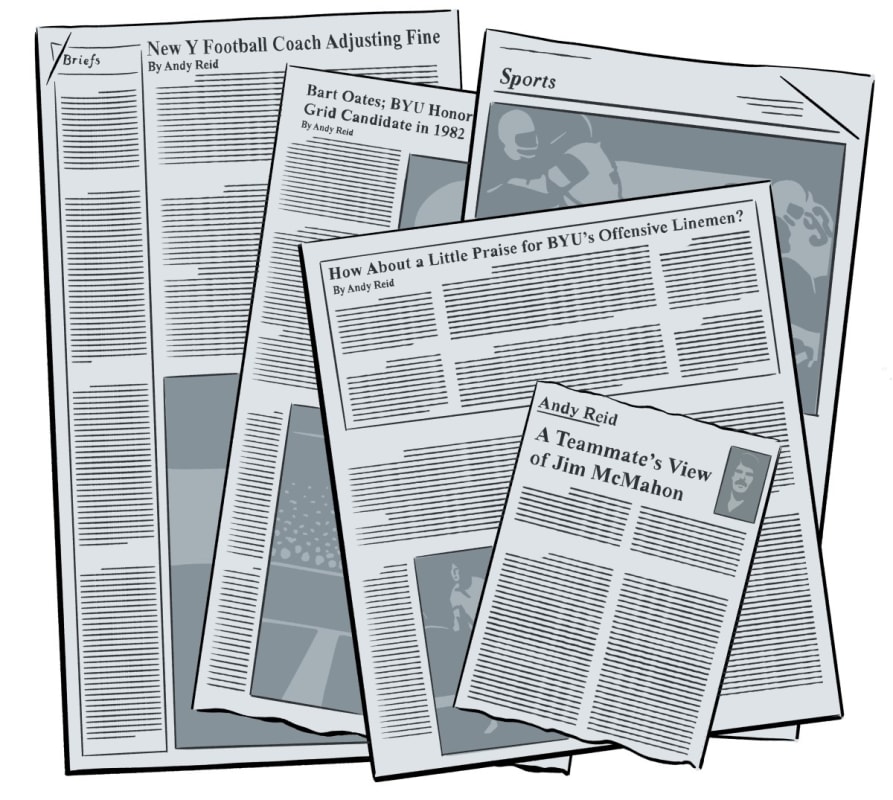

While on the Cougars’ roster (and later as a graduate assistant), Reid also penned at least 12 stories at the local paper. He wrote almost exclusively about the team he played for, which would have been frowned upon as recently as maybe 10 years ago but wouldn’t be as hazardous to an aspiring hack today.

Using his knowledge of the program, he gravitated toward the kinds of topics that most sportswriters back then either overlooked or didn’t have the perspective (or access) to adequately cover. Reid wrote about specialists and their importance—“nobody wrote about them. I saw an opening I could at least touch on.” He wrote about coaches and how they operated, where they made a

difference. He spoke with (and quoted) the scouts he’d later lean on when he became a coach.

His earliest writings featured an editor’s note tacked above the byline. That wording changed (and in some cases, vanished) in later stories. But the most common version went, “Andy Reid is an offensive tackle on the BYU football team. Today he writes . . .”

Reid’s work took on a variety of styles. He wrote columns. He wrote analysis. He also wrote mini profiles, trend stories and a little news. In one instance, he defended McMahon by comparing him to Abraham Lincoln.

“We were all friends,” Reid says (meaning the Punky QB, not Honest Abe). “I was with all of them. Whatever kind of story, they understood.”

In both pursuits, undertaken in the same time and place, Reid was learning storytelling and coaching. He later would come to realize that they’re largely the same thing. Over the years, Reid’s writing ambitions have been assigned a certain significance, a path he wanted rather than a realistic potential option. But Reid says, more simply, that he thought about a writing career. He didn’t dream about one.

Still, curiosity defines him now, as it has through most of his life. Reid sometimes toiled as a peanut vendor at Dodger Stadium near his childhood home. He started journaling in his junior year of high school and wrote almost every day. He studied English at BYU. His parents gave him an SI subscription “when I was a pup.” He adored Paul Zimmerman—“he was phenomenal,” Reid says. He saw the estimable football scribe as a North Star of sorts. Dr. Z didn’t just write about football. He analyzed the game through his writing, conversations and observations. Reid also tried to imitate Jim Murray, the iconic sports columnist at the Los Angeles Times whose use of humor informed Reid’s stylistic leanings.

Already, Reid possessed critical skills needed for sportswriting. He understood the sport he wrote about, had a firm grasp of the subject matter. He also knew people within that world, meaning he had sources.

His copy from those Daily Herald pieces is clean: meaning mostly grammatically correct, solidly stitched together and illuminating in places, with only a few typos or obvious mistakes.

Reid’s opportunity with the Daily Herald came when a writer—who traveled with the team and knew that Reid dabbled in the written word—asked him whether he wanted to occasionally cross the street. Reid made up his process as he went along. He came up with his own ideas. He reported them (but not in a ton of depth). He tapped out his pieces on a typewriter. And, he says, they were lightly edited, “which is nice”—making him the envy of every writer who ever lived.

Reid says he told his editors at the outset that he wanted to write about the human beings underneath those helmets, about characters like McMahon. He wanted to take readers where they couldn’t otherwise go.

Illustration by Madison Ketcham

Big Red, with his coach-issued khakis and suspiciously similar outfits, never seemed to value style. His writing, even from a limited, long-ago sample size, proves otherwise. It’s heavy on metaphors, description and imagery.

For example, here’s one lede on an assistant coach: As the sun rose over the cool Pacific Ocean and the beautiful California coast, a special sea-going creature was missing from the turquoise waters of San Diego Bay . . .

In Reid’s writing, linebackers are “high-tempered people.” One older LB in particular is “stocky” in body, with a receding hairline and an “agitated slant of his eye brows, round face and critter-looking mustache . . . ”

Over his 12 stories, Reid makes comparisons to Rocky and comedian Rodney Dangerfield (twice!). He compares a celebratory game film review session (access!) to hot fudge being poured over vanilla ice cream. (He would, of course, later take his love of food into press conferences all over the country.) Offensive linemen are “seven Greek Gods” and “big bears” who “prowl the high mountains above.” One has a “very honorable bear growl.” Another is “maybe the gentlest bear ever to roam the earth.” Kickers are astronauts, who, “while not touring in orbit,” study accounting. Biceps “can stop oncoming freight trains.” A teammate is “baby-faced” and “prematurely gray.”

An elite lineman, in another story, “looks like a rosy-cheeked incredible hulk as he toys with ferocious defensive linemen.” A defensive end from Hawai‘i is a “hula sacker” and “situated on a 6-5 frame and bonded with grease lightning.” A lack of respect for the big hogs up front requires “an injection of Mom’s tenderness.” That’s a good line!

Reid used his teammates’ and coaches’ nicknames, lending a vibe of familiarity. In one piece, he noted how two linemen once scarfed down 30 baskets of fish and chips in one sitting at Skipper’s Seafood. Good color, as we say.

Typical of all younger writers, his work would benefit from some obvious fixes. Questions posed that go unanswered. Cringe-inducing sentences. Repeated notions. Mixed metaphors. (“This article is dedicated to the Bear wall that makes the star twinkle in the massive, barren sky.” We’ve all been there.) An overreliance on movie metaphors.

For a professional evaluation, I sent his clips to Carl Nelson, an esteemed curmudgeon who ran the New York Times sports desk night after chaotic night. Intimidating as hell. Tall. Blunt. Smart. Nobody better. C-Nelz, we called him during my six and a half years with the paper. After reading Reid’s canon, C-Nelz responded how only he could. For an elite communicator, his emails and text messages are often long strings of thoughts broken up by only a parade of ellipses—teenaged Justin Bieber fan vibes.

His response started with, “Get me rewrite! Or a strong editor . . . haha.”

Then he ramped up the humor. “Dunno whether Andy majored in astronomy or earth science but I read more metaphors Re stars/constellations/boulders/rocks/diamonds/gems than any other sports articles in my 41 years in the newspaper biz. Lotta cliches/overwrought repetition of words to support ledes/themes. Yes Andy the reader gets the point there r lotta gems/stars on the team.” This might have induced some PTSD.

C-Nelz blamed Reid’s editors for any typos that had snuck onto those pages. Nelson also liked Reid’s ideas and the elements he had chosen to construct stories. But he found Reid’s insights lacking in depth in a way that I did not. Since Reid played for the team, C-Nelz expected more of them. Still: “Style was quite readable/no laborious sentences. breezy . . . Overall needed more depth which good editor would insist upon. I would definitely hire him as an intern!”

That’s a bar many “real” sportswriters never cleared.

Robert Deutsch/USA TODAY Sports

If you read it closely enough, Reid’s writing provides clues to the career he actually chose. In one story, for instance, he cites the grades for BYU’s offensive line—a full 98% success rate in their previous outing. He counters that with insight into the next opponent, Colorado State, which he notes isn’t a good team but features a strong D-line. That’s a future coach.

In another piece, Reid describes a teammate and the Eagles’ take on him—that he should shift to nose guard, because he was strong. That’s scouting! In the same piece, he also projects a lineman teammate would be a perfect fit with the Chargers and wrote, “his attitude is what makes every coach enjoy his job.” He was already thinking like one, apparently.

Perhaps Edwards, who died in 2016, sensed all this when he approached Reid after his senior season and encouraged him to become a coach. Reid listened and joined the staff as a graduate assistant in 1982. But it’s not like he transformed into an entirely different human. “My players, they’ll probably tell you, I’m a storyteller,” Reid says. “My creativity comes out a little bit, whether calling players or [in] the messages that I don’t want to be stale and repeat.”

One example: In early 2020, before the Chiefs’ win over the 49ers in Super Bowl LIV, Reid took a whiteboard scribble sequence that added a fifth receiver and named the wrinkle Dr. Octopus. All those appendages and whatnot. That’s a story. Same aim, different medium. And the proof is in those newspaper pages, which have now turned a golden shade of yellow, just like the Lombardi Trophy that Reid held overhead last February.