André Dao’s remarkable debut novel began as an investigation into his paternal grandfather’s ten-year detention without trial by the Vietnamese government, from 1978, three years after the war ended.

It turned into a full quest for the truth of his family history, which spans the two Vietnam Wars: the first, with occupying France, from 1946 to 1954 (the first Indochinese War); the second, 1954 to 1975 (the second Indochinese War, or the American War).

Dao was born in Australia to Vietnamese refugee parents. He’s a writer, editor and artist – and a refugee advocate who co-founded of Behind the Wire, an oral history project documenting people’s experience of immigration detention.

Review: Anam – André Dao (Hamish Hamilton)

His novel is not based solely on data, recorded materials and official documents: this proved impossible in dealing with repressed memory, and rendering the complexity of Dao’s family story. Instead, Anam is a work of imagination in which the narrator tries to allow all the rival voices and conflicting versions of this saga to be heard.

From Hanoi to Saigon, Laon to Boissy-Saint-Léger, and Melbourne to Cambridge, this richly layered novel invites the reader to join Dao in disentangling different narrative threads.

Forgetting and remembering

Readers familiar with Vietnamese history will notice the peculiar spelling of the book’s title: Anam, with one “n”. It’s a homonym of “Annam” (Pacified South), a name imposed on Vietnam by the Chinese imperialists in the seventh century and perpetuated by the French colonialists. It refers in fact to “anamnesis”: that is, forgetting and remembering.

Anam is therefore not a physical place, but an imagined, mythologised “time-place”, one the narrator has created and made his own through the torturous process of writing. He connects the reader with his story, which resonates beyond the Vietnamese diaspora to touch all diasporic peoples haunted by dispossession and unbelonging. We accompany him on his journey.

Reflecting the missing “n” in Anam, the book intriguingly opens with two short entries, puzzlingly labelled C and D. This points not only to the missing entries A and B, but also their recovery at the end of the novel – in the form of a series of derivatives: A, B and C.

Visually, this evokes Anam’s central tropes of memory loss and retrieval. It highlights the novel’s painful false starts – and its completion, as the narrator attempts one last time to relate the interwoven stories of his family in three chapters, named “Michaelmas”, “Lent” and “Easter”.

The significance of this deliberate structure is twofold. It references the three important periods in the Catholic calendar, and the three academic terms at Cambridge University, where the narrator completes his thesis on the life story of his grandparents.

It’s a mise-en-abyme, highlighting the embedding of one story within another, in an intricate weaving of voices that alternates between the narrator’s present and his family’s past. As a religious framework, it supports the narrator’s endeavour to portray his grandparents through their Catholic faith.

Read more: Model minorities and murder: Tracey Lien investigates the Vietnamese Cabramatta of the 1990s

Generational journeys

The first chapter, “Michaelmas”, refers to the celebration of Saint Michael, the saint of protection in time of peril. It’s presented as an investigation that aims to piece together the grandfather’s perilous journey – from his commitment to the Viet Minh cause (the Communist national independence coalition) in the 1940s, during the first Indochinese war with Vietnam’s French occupiers, to his fight for survival in the infamous Chí Hòa Prison in the 1980s.

This chapter is motivated by questions related to the grandfather’s choices: his desertion from the Viet Minh to join the (Western-backed) regime of South Vietnam, his forgiveness of his jailers, and his silence in the face of injustice. It convincingly demonstrates how, by blending facts and fiction, the narrator comes to an understanding of his grandfather’s decisions.

Anam inhabits the lives of real political figures such as Nelson Mandela and Trịnh Đình Thảo, a famous French-educated Saigonese attorney whose participation in the anti-war and peace movement in Vietnam landed him in Chí Hòa Prison numerous times. Their fight and willingness to sacrifice for their cause shed light on the narrator’s enigmatic grandfather.

Dao’s creation of a fictional Vietcong ghost in Chí Hòa Prison serves the same purpose. The grandfather and the ghost are on opposite sites in the Vietnam War and motivated by different ideologies, but as fellow inmates, they share the same suffering and the same fate.

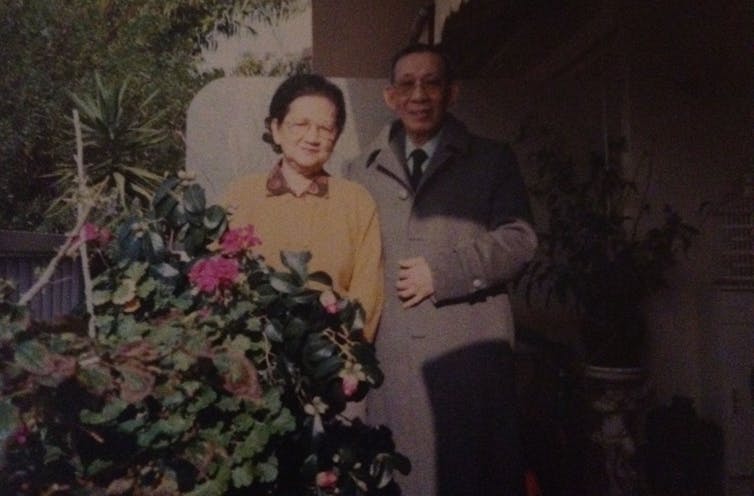

The cover photo of the grandfather seems to suggest he’s the principal character in Anam. But the second chapter, “Lent”, focuses on the grandmother in Laon, France.

Her story reflects the novel’s themes of sacrifice, love and hope. A migrant mother, her life is characterised by her selfless care for her children and her faithful love for her husband, incarcerated in Vietnam.

Despite her willingness to talk about herself, starting with her childhood in Hanoi, her marriage and resettlement in Saigon, then her flight to France, the grandmother remains an elusive figure. The narrator feels compelled to rely on different perspectives and multiple voices to cast light on his grandmother and her life experiences.

Imaginative writing (in addition to family conversations and recorded interviews) is again an effective tool for the narrator, as he faces the complex task of telling his grandmother’s story.

And he repeats his use of mise-en-abyme by inserting a minor (fictional) novel, The Crowned Mountain, (or Montagne Couronnée – the name of Laon’s Cathedrale Notre Dame de Laon) within the novel, which captures the essence of the grandmother through the symbolic figure of the Madonna.

The last chapter coincides with the completion of the narrator’s academic term and his thesis. Here, his long journey into writing his family’s past comes to an end. Fittingly, “Easter” signals resurrection and new beginnings.

The grandfather symbolically returns to life, after his release from prison and his reunification with his family in France. And there’s renewal through future generations: in the form of two long, moving letters, labelled A and B, which the narrator addresses to his baby daughter. (These letters overlap the missing entries, A and B, at the start of the novel.)

With these letters, the narrator’s daughter becomes custodian of her great-grandparents’ memories – and the full story of Anam has been told and transmitted.

Read more: War's physical toll can last for generations, as it has for the children of the Vietnam War

A fine example of a global novel

Uncompromising and honest, Anam is a brilliant book of immense scope. Dao has kept the legacy of his grandparents alive through his literary creation. He raises moral questions of doubt, complicity and guilt, while showing compassion and generosity towards all choices.

The novel’s themes are not uncommon in Vietnamese diasporic literature: separation of family into enemy camps, the trauma of war and dislocation, the difficulty of retrieving and representing memories, hope and renewal. But Dao handles these themes in an original and convincing way, appealing emotionally and intellectually to his reader.

Through his compelling narrative strategy, he lays bare the writing process, allowing us to take part in his experimentation with different forms and narrative styles, and transporting us across all borders: not only of geography and time, but linguistic, political and cultural boundaries.

Dao’s quest to include all perspectives means both Western and Eastern philosophy and beliefs are called upon to shed light on the past. Pivotal questions of social justice and forgiveness are illuminated through the Catholic concept of God’s love and mercy, but also through the Vietnamese concept of “phúc đức”, in which the forebear’s moral conduct is passed on as a legacy of blessings from one generation to the next.

In terms of thematic, linguistic, and cultural scope, Anam is a fine example of what a global novel should be like. It beautifully connects East and West; Europe and Australasia; Oceania and the Middle East. It is an insightful addition to a series of acclaimed books on memory, war, and migration by Anglophone writers of Vietnamese origin – such as Nam Lê’s The Boat, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Nothing Ever Dies, or GB Tran’s Vietnamerica.

Read more: A journey with The Boat: students connect over a common story

Dao gives us a privileged reading experience. Throughout the novel, he makes us feel the immensity of the task he has set himself – to ethically tell the story of Vietnam, of forgetting and remembering. And he makes us feel the full weight of his literary and family commitment to this project.

To use his judicious metaphor, a book on family memories is not a memorial to the past, lifeless and cold, like “a slab of black granite”. It’s a “house with many rooms” and “many windows”: each with a different angle, each looking out on a different memory, each perspective equally valid.

Anam encourages us to reflect on the ethics of forgetting and remembering. And it inspires us to think of a way to create our own houses, from which to tell the stories of our past.

Tess Do does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.