Uncommon Courses is an occasional series from The Conversation U.S. highlighting unconventional approaches to teaching.

Title of course:

“LGBTQ Antiquity: A View from the Mediterranean”

What prompted the idea for the course?

I study Greek and Latin literature and have noticed that ancient authors wrote about sex, homoerotic feelings or relations, and gender more often than we assume.

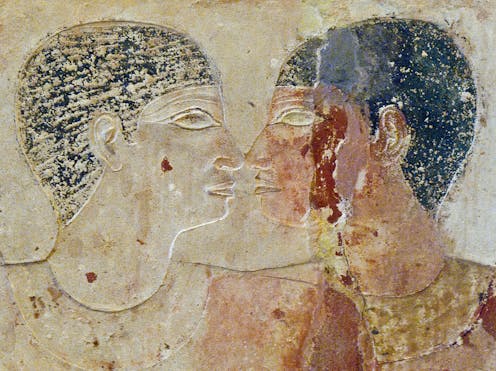

A few figures from ancient Mediterranean mythology are sometimes held up as LGBTQ ancestors – such as the Greek gods Apollo and Zeus, who both loved other men. But in a mythology course I taught in the fall of 2021, I found myself highlighting a number of other stories about same-sex attraction and gender variance beyond a strict male-female binary. For example, spells from Egypt show that there were women who tried to get other women to fall in love with them.

Students responded with such curiosity and excitement that I decided to create a stand-alone course that would focus exclusively on these topics.

What does the course explore?

The course explores literary texts from the ancient Mediterranean – including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and Roman Italy – in which authors describe relationships that can be said to fall under the LGBTQ umbrella. We read the texts in chronological order, rather than grouped by theme or identity. This allows students to encounter the texts relatively label-free, since the words U.S. society uses to talk about gender and sexuality today – like “gay” or “transgender” – do not always align with ancient understandings.

Why is this course relevant now?

Assaults on members of the LGBTQ community, especially trans folks, are rising in the United States: both through legal means in a number of states and through physical attacks and hate crimes.

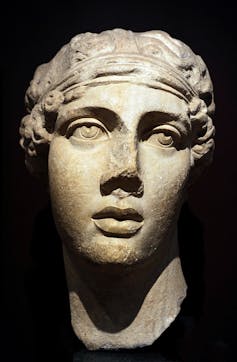

My goal is for students to take courage and hope from knowing that same-sex relationships and gender diversity have existed in various guises for millennia. In antiquity, homosexuality was not considered an identity category the way it is today, making it hard to determine if and how LGBTQ-like people were discriminated against, but they certainly were not always met with contempt. For example, the body of Hermaphroditus, a god whom Greeks sought out for help with fertility and child care issues, combined female and male characteristics.

I also want students to connect with the past as a way to feel rooted and validated. In this, I took a cue from trans activist Leslie Feinberg, who wrote in the 1996 book “Transgender Warriors,” “I couldn’t find myself in history. No one like me seemed to have ever existed.”

What’s a critical lesson from the course?

LGBTQ-like individuals have always been here, although modern conceptions of self, gender and sexuality cannot be mapped directly onto the past.

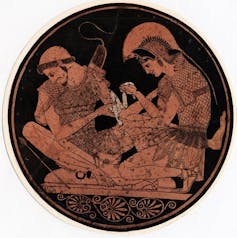

The identities we know today were unknown then: The concept of homosexuality as a distinct sexual orientation or distinct kind of behavior did not exist. For instance, elite men in ancient Athens often engaged in same-sex relationships with men alongside their marriages to women. Those who were in exclusively homoerotic relationships, however, tended to be ridiculed.

Another critical lesson is that language matters. The words we use today are often inadequate to capture how social status or age intersected with one’s gender in the ancient Mediterranean. Take the Greek word for a woman or wife, “γῠνή.” Typically, this word refers to an upper-class woman, rather than, say, one who is enslaved or a foreigner. Norms around sexual activity depended on a person’s social status, age and gender.

What materials does the course feature?

Students come into the course expecting to encounter celebrated characters such as the poet Sappho, from the Greek island of Lesbos, whom lesbians have regarded as an ancestor.

However, we also read less famous authors, such as Lucian of Samosata, a Syrian-born satirist from the second century C.E. In one of his dialogues, a sex worker tells her friend about an encounter she had with two other women, one of whom describes herself as “quite like a man.”

Not all authors are sympathetic. John Chrysostom, archbishop of Constantinople at the end of the fourth century C.E., vilified people who engaged in homoerotic acts or homosexual relationships as criminals, mentally ill, diseased or diabolic. Many of these views are still being promulgated by religious leaders today.

The course also explores the lives of some Byzantine saints who were seen as women before they entered a monastery or became ascetics. Yet their self-punishing practices, such as extreme fasting, transformed their bodies, and the surrounding communities started to see them as men. These stories, which aimed to uplift their audiences, serve as a reminder that cross-dressing and gender variance were not always seen as objectionable.

Tina Chronopoulos does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.