While ancient Greece is one of the best known cultures of antiquity, there are no surviving historical narratives covering events between 1200 and 760BC. This period has traditionally been viewed as a “dark age” on account of the lack of preserved written sources after much of the Mediterranean suffered a societal and political collapse.

The Greek iron ages occurred within this period. But, because of the lack of documents, till now historians have been working with a timeline, which uses pottery styles from Athens as its basis. Devised in the late 50s and 60s by the historians Nicolas Coldsteam and Vincent Desborough, it has been widely held that the iron ages begun in 1025 and ended in 700BC.

The “Greek renaissance”, from 760BC to 700 BC, emerged in the iron ages’ last period, known as the late geometric. This was a time of rapid economic and demographic growth that saw the adoption of alphabetic writing, the emergence of the Greek city-states, panhellenic sanctuaries and the establishment of Greek colonies abroad.

Such huge strides in 60 years, means that the period is considered extraordinary. However, new research from Assiros and Sindos in northern Greece, as well as Zagora on the Cycladic island of Andros suggests that this timeline of the Greek iron age is wrong. My recent work with the archaeologist Bartłomiej Lis on protogeometric pottery from the site of Eleon supports this view.

Together, our research indicates that the Greek dark ages could have been shorter and the Greek renaissance much longer than previously thought. This shows that Greek society was more resilient to the societal collapse that preceded the iron age than previously believed.

New pottery samples

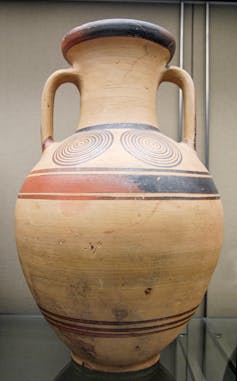

Our study centres on a vessel discovered in 2013 by a team of archaeologists from the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia and the Canadian Institute of Greece in a shrine dating to the last half of the 12th century BC in the ancient town of Eleon. This vessel, found crushed on the shrine’s floor, features distinct sets of concentric circles pivoting around a central axis (a type of compass-like device) on its surface. A vase like this being discovered in a such an early context is unprecedented in central Greece.

The vessel’s concentric circles are characteristic of the protogeometric style that Coldsteam and Desborough’s believed to have emerged in Athens during the last half of the 11th century BC.

Coldsteam and Desborough established dates for the Greek iron ages through careful documentation of Greek pottery fragments in the Near East (an area covering roughly that of the modern Middle East). These fragments were found at sites which had been destroyed and levelled during historically attested wars.

So, using Near Eastern and Egyptian historical records of these incidents and by identifying the specific styles of the pottery fragments, Coldsteam and Desborough were able to give them specific dates. These were the protogeometric (1025-900BC), early geometric (900-850BC), middle geometric (850-760BC) and late geometric (760-700BC). The last being equivalent to the Greek renaissance.

Our research challenges this timeline and argues instead for an origin of the Protogeometric style during the 12th century BC in northern Greece and so proposes a new start date for the iron ages.

Our argument is supported by petrographic (analysis of thin sections of the pottery under a microscope) and chemical analyses conducted on the vase that show conclusively that it was imported from the lower Axios Valley. This happens to be the region where two other studies found results similarly challenging Coldsteam and Desborough’s chronology of the early iron age between 2000s and 2020s.

As well as bolstering the revised timeline, our research introduces an added layer of complexity into the debate because the vessel from Eleon was found within a layer of Mycenaean pottery dating to the 12th century BC.

In the conventional chronology, Mycenaean-style pottery was produced from the 16th to 11th century BC and was succeeded by the protogeometric style towards the end of the 11th century BC. As Athens was believed to be the centre responsible for creating the protogeometric style, no examples of it should be found in contexts earlier than the late 11th century BC.

The discovery at Eleon suggests that the protogeometric and mycenaean styles co-existed for a 100 years, rather than occurring one after each other. This means that the dark ages of Greece, could be much shorter than previously believed since the late geometric – and so the Greek renaissance, which saw the introduction of the alphabet – would begin over 100 years earlier.

The revised chronology emerging from our study proposes news dates for the iron age periods with most beginning around one hundred years earlier that believed. For instance, the protogeometric would begin around 1,150BC and end around 1,050BC instead of beginning 1025BC and ending 900BC. By moving all the start dates of the earlier periods forward, the late geometric becomes much longer since it would begin around 870BC rather that 760BC.

So, with its new start date of 870BC and its fixed end date of 700BC, the Greek renaissance spanned almost 200 years. It is certainly much less impressive then to consider all the strides of the period happening in two centuries instead of four decades.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Trevor Van Damme receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.