The ancient Egyptians were prolific record keepers. For thousands of years, they jotted down everything from legal documents to literature on papyrus rolls and tablets of wood and stone.

But there’s one practice central to ancient Egyptian life — and death — that hasn’t been described in detail.

“There are so many texts, but there's no handbook of Egyptian embalming,” Philipp Stockhammer, an archaeologist at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, tells Inverse.

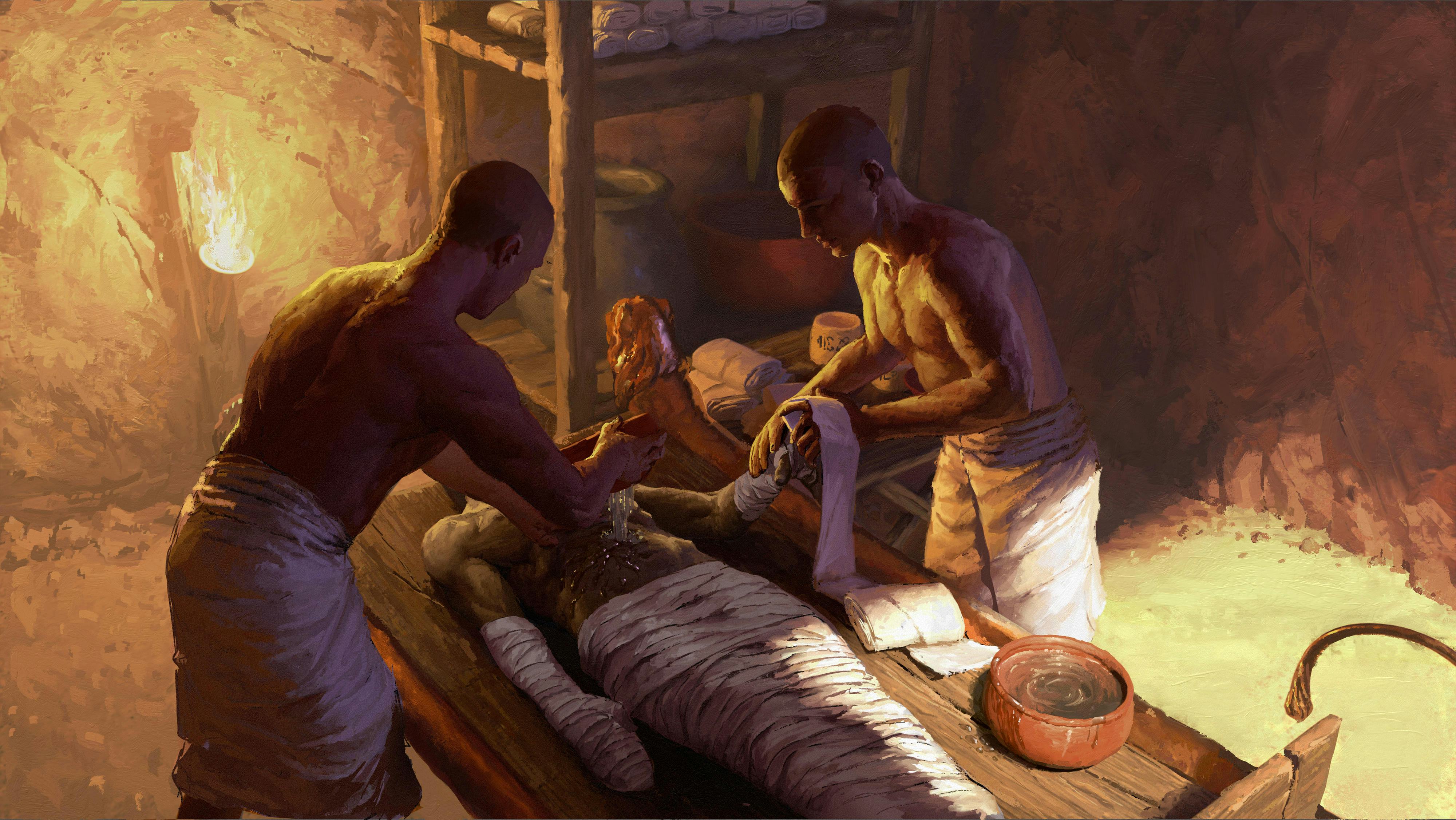

The nuts and bolts of how ancient Egyptians turned would-be decaying bodies into immortal mummies remains largely a mystery. But a new study in the journal Nature investigates artifacts from an embalming workshop and sheds some light on the intricate process.

Here’s the background – In Egypt’s Saqqara region, the most noticeable structures are the pyramids. But buried beneath the ground near the pyramid of King Unas is a chamber where the bodies of the dead were once prepared for burial.

“Nowadays, what you see on top of the ground are some basins and some mud brick walls in ruins,” Stockhammer, one of the study’s authors, says. Two shafts lead into the ground; one to the embalming chamber, and the other to an underground burial complex.

The embalmers here wouldn’t have handled the bodies of royalty like King Unas. Rather, the workshop would have been equivalent to a modern-day funeral home for Egypt’s middle and upper classes, including people like priests, government officials, and rich merchants.

Depending on how much money someone had, they could request a range of services for their deceased family members. Organ extraction, washing the body in sacred oils, and even providing a burial spot in the underground chamber were all on the table as long as you could pay.

“It was really an all-inclusive package,” Stockhammer says. The site was discovered in 2016, largely due to the work of his colleague Ramadan Hussein. Hussein was an Egyptologist and helped excavate the workshop, and was also a co-author on the study. He died unexpectedly in 2022.

To date, the embalming workshop is the only one ever discovered from ancient Egypt.

By analyzing storage vessels that once aided embalmers in their secretive work, Stockhammer and colleagues pieced together exactly what ingredients they used to prepare bodies for the afterlife.

What they did – For the Nature study, researchers ran chemical analyses on residue from 31 vessels from the workshop. Many bore engravings with the name of the substances inside, and some even had instructions for use.

A mixture of animal fat and resin from Burseraceae trees was used “to make the odor pleasant,” according to the inscription on one vessel. Different mixtures of plant oils, beeswax, and resins were specifically used to anoint the head.

The analysis even revealed the chemical makeup of some important substances mentioned in ancient texts. One, called antiu, has often been translated as myrrh or incense. “There are so many — mostly offering texts — [that] say that you bring antiu as an offering to the gods,” Stockhammer says.

But antiu and myrrh, which is a resin from a certain type of Burseraceae tree, seem to be different substances. Vessels marked antiu in the workshop show it was a mixture of oil from cedar trees, cypress or juniper trees, and animal fat.

The ingredients also revealed a surprising truth about ancient Egypt during the time the workshop was active in the 6th and 7th centuries BC.

“Cedars and Junipers don’t grow in Egypt,” Stockhammer explains. “[They] definitely came from the Mediterranean … the Levant, probably.”

Many of the substances regularly used in embalming came from faraway lands, hinting at the presence of long-distance trade networks that researchers know little about.

What’s next – Though embalming was an important chemical and spiritual process in the ancient world, the step-by-step guide of how people actually did it is still being written.

“Basically, this workshop was the first time that we really are able to understand the recipes of embalming,” Stockhammer says, “which is just fantastic.”

In the future, Stockhammer plans to continue studying vessels excavated from the workshop, many of which haven’t been analyzed yet. He thinks it would also be interesting to one day replicate those recipes to embalm animal specimens and see how well they work.

But there’s still a lot more to understand about the process. How oils were mixed or warmed, for example, isn’t clear yet.

What is clear, Stockhammer says, is just how much knowledge and skill went into the process of embalming.

“It's a specialist knowledge that was passed down in families or workshops over the centuries,” he explains. “And we are now, for the first time, able to get at least a glimpse into the complexity of this knowledge.”