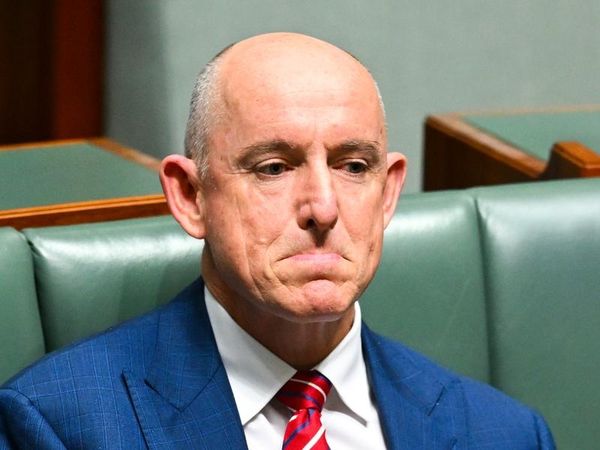

As the explosive Synergy 360 controversy shows, one can never truly take comfort in the idea the worst has already come to pass with Stuart Robert.

The man is a flat circle, evangelically unburdened by the weight and sting of conscience. His ensuing and almost preternatural ability to spread scandal thin and wide is not unlike that of a toxic weed: the scandal lingers for years, defacing the trust that sits at the heart of our democracy.

But absent a full panorama of Robert’s 15-year scandal-distinguished political career, it would be too easy to cast doubt on or downplay the significance of his legacy.

After all, he belonged to a government marked by unrivalled and unconcealed contempt for those conventions designed to ensure propriety — one in which lies were habitually brandished against not just facts but reality itself, where government made no secret of trying to bend the rule of law to its will, and where corruption, incompetence and failing upwards became synonymous with the natural order of things.

The efflorescence of this crisis of moral collapse didn’t originate with Robert, but nor was his role in this era of endless scandal and the shameless spiv a minor one.

On the contrary, this “fascinating cat” was a “clinger” and a “barnacle”. He was Scott Morrison’s “Brother Stewie”. A person who conflated his unbroken and perverse presence in Parliament not with degraded and vanishing norms but Pentecostal providence. Someone who deftly pranced from one gilded protective cage to another for the entirety of his worthless career and more or less got away with it.

In this sense, it’s tempting to think of him as little more than a quintessential modern Liberal politician, plus more. But even that’s too charitable. After all, it’s not for nothing the Queenslander’s name appears alongside Alan Tudge and Scott Morrison on what Labor insiders have dubbed “Bill’s kill list”.

Indeed, it’s almost poetic that one of the most telling hints to Robert’s cavalcade of rank opportunism and disgrace can be found in a Google search of his name plus the words “first speech”. Besides, as you’d expect, one or two benign links to his maiden speech, the search returns some news links to one of Robert’s first major scandals: the notorious “cash for comment” saga.

That particular storm possessed many of the hallmarks of what we might call the paradigmatic Stuart Robert scandal: chief among them real or perceived conflicts of interest, an LNP donor or two, something that to all appearances amounted to a quid pro quo, potential abuse of public office, boilerplate denials of wrongdoing, and a gaping shame deficit.

But the seeds of the scandal are also telling. Partly because they show nothing was ever for nothing when it came to Stuart Robert, and partly because they explain why his many scandals so frequently folded into one another, none separated by any long, colourless stretch of good behaviour.

As it happens, the controversy turned on a bizarre though hardly memorable speech Robert delivered in Parliament in late 2012, where, for no blindingly obvious reason, he felt compelled to defend the honour of a Gold Coast property developer by the name of Sunland Group, then steeped in controversy. In the four years that followed, the speech lay dormant, gathering dust, having mistakenly been filed as little more than a forever footnote to unexplained Stuart Robert peculiarity.

And so it arguably would have remained, were it not for the pesky revelation that large sections of the speech had been penned not by Robert but by the developer’s lobbyist, Simone Holzapfel, herself a major LNP donor and former long-time staffer to Tony Abbott.

As death follows life, what ensued were yet more revelations, this time concerning sizeable donations to the LNP and the Stuart Robert Fundraising Foundation (now called the Fadden Foundation), all from Sunland’s founder and chairperson, Soheil Abedian, and Holzapfel herself, and all timed within months of the speech. Robert, for his part, was also revealed to have breached guidelines by taking it upon himself to lobby the Gold Coast City Council for a $600 million Sunland development outside his electorate, but perhaps that’s by the by.

He waved the entire controversy away in predictable gormless Liberal Party fashion, telling reporters that any suggested link between the donations and the speech was “outrageous”, “offensive”, “incorrect and scurrilous”, though he never denied Holzapfel authored the speech.

In all likelihood, however, the chances are none of this truly weighed on Robert’s mind. This isn’t offered as some profound insight into the deep purgatory that is the man’s subconscious, but rather as a reflection of the fact Robert by then had probably already assumed the foetal position, having recently been dumped from the Turnbull frontbench in a classic Friday afternoon taking out of the trash.

His sacking, tepid though it was, was linked to his alleged attempt “to pass off a trip to China to help out a Liberal donor mate as ‘personal business’” in a separate blossoming controversy stamped with all the imprimatur of a very Stuart Robert scandal.

All this, it bears emphasising, unfolded against the backdrop of yet other scandal-grabbing headlines, involving such things as the mysterious giftbag of Rolex watches from a Chinese billionaire, the million dollars’ worth of taxpayer-funded VIP flights Robert and then-defence minister David Johnston had racked up in the space of three months, as well as reports of Robert’s staff having “lectured” and insulted a serving RAAF member’s wife over the phone.

There was also the truly weird Anzac Day tweet of 2016, where he claimed more defence force personnel used negative gearing than “surgeons, judges, anaesthetists and psychiatrists combined”. To this day, precisely what inspired Robert to tweet such inane pabulum remains a mystery no one’s rightly cared to solve.

But beyond this, the public would soon learn that Robert’s penchant for scandal was such that it literally commenced on day zero of his election to Parliament, with his election possibly falling foul of section 44 of the constitution.

In true Robert style, ASIC records and his register of interests revealed he was a director and shareholder of several companies when they were awarded government contracts worth tens of millions of dollars between 2007 and 2010. When pressure was brought to bear on him to do the “honourable thing” and resign, Robert dissembled and moaned, arguing he’d carefully structured his business affairs to avoid the long arm of the constitutional provision, though he declined to explain how.

And as we know, the scandal only deepened when it was revealed he’d involved his elderly parents by using their personal address to disguise an ongoing interest in the companies after 2010, with apparently neither their permission nor knowledge.

But ever the flat circle, Robert survived the storm through a slick combination of mendacity, spin and noetic disarray — a direct beneficiary, of course, of a political system by then so debased and weighed down by the stench of years of institutional decay that the scandal faded like all those before it.

Indeed, less than a year later in 2018, he rose again, finding himself returned to the frontbench after having prayed with Morrison in the moments before the Turnbull coup that “righteousness would exalt the nation”.

Naturally, Morrison was later asked how he managed to reckon Robert’s presence in cabinet with his chequered record, to which Morrison responded in typical Morrison style: “Because he’s done an outstanding job in the one that he’s been doing,” he intoned, in one of his first prime ministerial moments of national gaslighting.

It bears pointing out Morrison said as much notwithstanding added layers of scandal, such as Robert’s skirmish with the Queensland Crime and Corruption Commission over possible unlawful conduct in local government elections (in which Robert was cleared of wrongdoing). Not to mention revelations he’d billed taxpayers in the order of $20,000 to visit a Ugandan-based Pentecostal church whose preacher — described by Robert as one of the “great influences” on his life — stood accused of inciting waves of horrendous violence against gay people.

But never mind. These too would prove scandal du jour, vanishing into the toxic blend of appalling behaviour that is Stuart Robert. Less than two months after his God-sanctioned return to the frontbench, this fascinating cat soldiered on in his seeming quest to personify distrust in the system with news he’d improperly billed taxpayers some $38,000 for home internet services since 2016.

Never one to suffer an anxiety of judgment, however, Robert didn’t apologise, instead settling with a placatory acknowledgment the bills were “higher than what the community expects”.

Ordinary people would tire of such schemes, but it was never so for Robert, for he is not ordinary. Within a month, this sad expression of a failed politician was again making waves, this time for soliciting political donations in exchange for information on the government’s potential response to the banking royal commission.

Some months later, he again made a splash for having curiously decided to base his ministerial office in Melbourne, with one of his two senior advisers living in Adelaide and the other based in Brisbane. It’s unclear whether the guiding rationale for this decision was ever truly disclosed, though why should we expect it to be: God presumably gives exalted people a reprieve on such matters.

All told, however, it would be a distortion of historical truth to suppose the sum of Robert’s political career was consumed only by self-interest and avarice. Ideologically, and with precision, he too played his part in an earnestly destructive government that left in its wake a country decidedly less equal, less kind, more divided, crueller, deader and more corrupt.

As minister for government services and the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), for instance, Robert presided over a push to cut costs and limit access to NDIS funding to certain services and categories of disability, entertaining the notion of excluding those with acquired brain disorders and foetal alcohol syndrome.

His undisguised aversion to certain classes of Australians similarly extended to the undeserving poor, whom he compared unfavourably with those many thousands of “decent” Australians who’d found themselves “unemployed overnight” when the pandemic descended.

And as education minister, he freely railed against public schools, blaming their “dud” teachers (as opposed to their lack of equitable funding) for the nation’s declining educational outcomes, many of whom he falsely claimed “can’t read or write”. Beyond also dipping into the history wars, he brazenly politicised tertiary research funding by using his ministerial veto to override six humanities research grants, declaring none would “contribute to the national interest”.

But in truth, Robert’s most telling and disgraceful failings lie in his handling of both the robodebt scandal and the evidence he gave at the royal commission.

It’s not only that he openly admitted to having lied on numerous occasions to the public about both the scheme’s integrity and the government’s plans to expand its reach in August 2019, suicides and incalculable suffering notwithstanding. It’s that he so readily, sanctimoniously and unconvincingly rearranged these moral failings into points of principle and honour, disingenuously telling the royal commission that his conduct owed to an overriding sense of duty to his cabinet, which in turn had placed him in a “dreadful position”.

In so doing, he adopted the guise of the hapless victim of circumstance, but one nonetheless courageous enough to demand the scheme’s end in November 2019. Except, of course, that his evidence runs entirely contrary to that given by the secretary of his department, Renée Leon, and her chief counsel, Timothy Ffrench, who said Robert knew of the scheme’s illegality far earlier but was loathe to put it to an end, conversely telling them: “we will double down”.

And so there it is: the carapace of power cracked open, laying bare little but unmoored self-interest and empty ambition, with the latter guided by a cruel and indifferent impulse to human misery. The sense of failure of the man is absolute; the political malaise, all-consuming.

Cementing one’s impression of Robert’s boundless cynicism was his announcement two months ago of his resignation via media statement: too spineless to front the media, but not too shameless to take another 10 days to officially resign.

For these reasons, Robert should by rights always be remembered as a person who declared himself to have a “moral compass” in his maiden speech, only to trash the notion in office, as though by careful design. A person who wilfully defied the public interest on innumerable occasions, and who was seemingly never once haunted by his undertaking not to abuse the people’s trust.

The man’s legacy, however, and that of the appalling government of which he was a part, also finds reflection in the newly established National Anti-Corruption Commission, which commences today. Whatever its shortcomings, it’s suitably fitting that the name Stuart Robert is among those already under consideration for referral.

It’s as though the past is finally catching up with Robert. Or perhaps he with it.

What are your thoughts on Stuart Robert’s legacy? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.