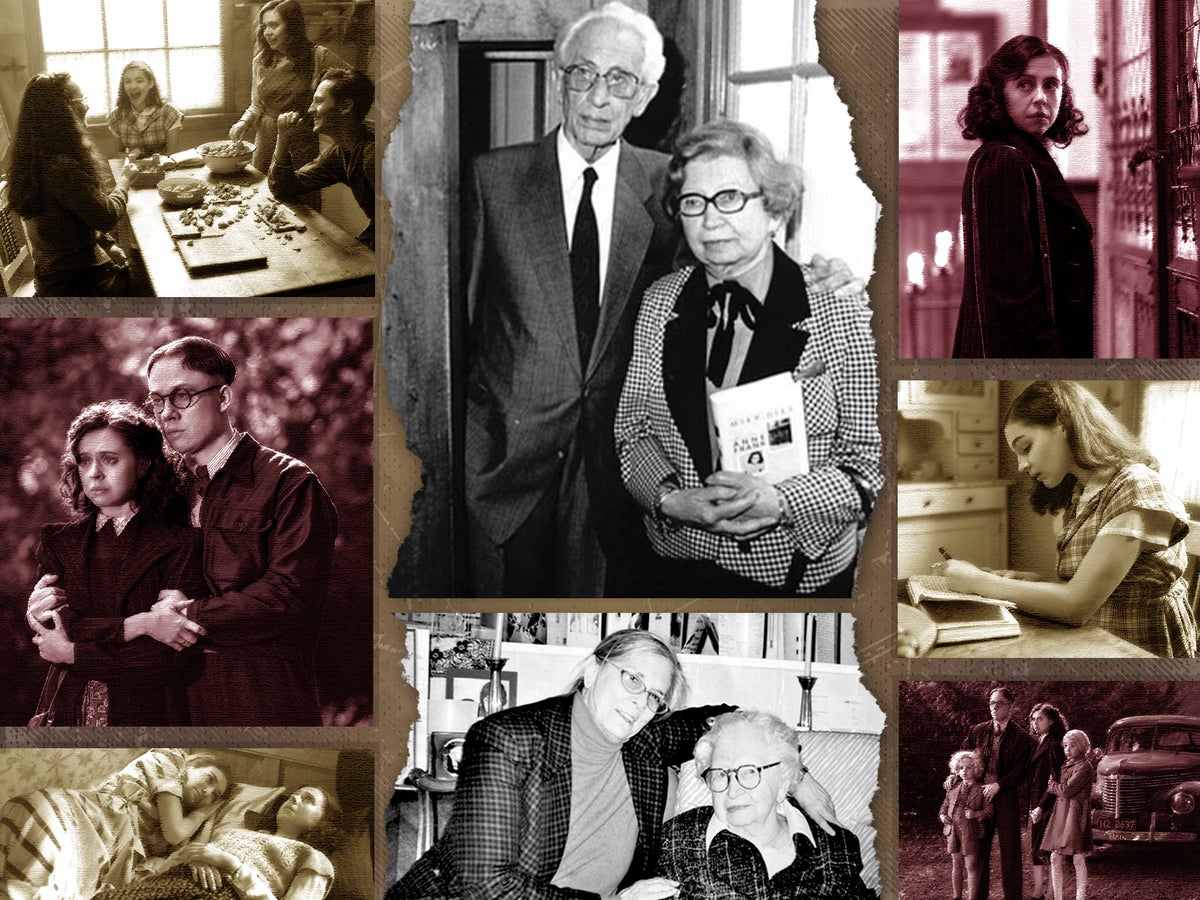

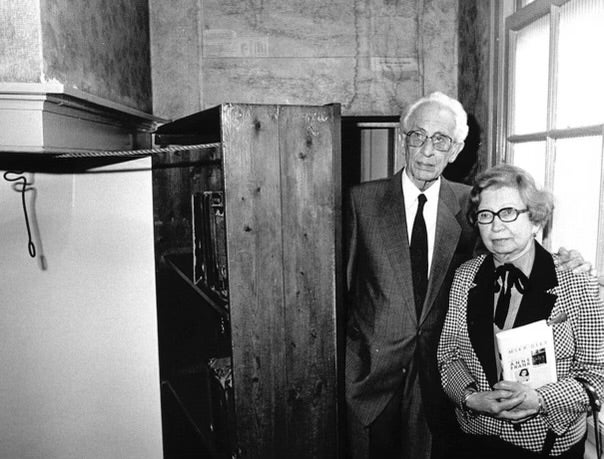

Years ago, decades after the establishment of the Anne Frank House as a museum in Amsterdam, an American writer and an older Dutch woman bypassed the lines outside and attempted to walk right in. They were stopped.

“I sort of stammered, ‘Don’t you know who that is?’” the writer, Alison Leslie Gold, tells The Independent of her companion. “And they didn’t. She was just another old Dutch lady.”

That lady was, in fact, Miep Gies, the Otto Frank employee who’d spent day after day for 25 months walking into and out of the very same building as she helped hide her boss and his family from the Nazis during the Second World War. It was Miep who, after the fugitives were tragically discovered, preserved the diary of Anne Frank and the young writer’s other works — eventually presenting them to Mr Frank, the family’s sole survivor, with the words: “This is the legacy of your daughter.”

Miep lived to be 100, dying the month before her 101st birthday in 2010, and in that century exhibited stoic heroism rivaled by few — but modestly downplayed by Miep and her husband, Jan. For years, towards the end of her life, Miep remained the sole survivor with memories from those furtive times in the annex, as the Franks and their friends endured perpetual terror in secret rooms while Miep and other helpers braved the occupied, heavily-surveyed streets.

Now, the new Disney+/NatGeo series A Small Light explores Miep’s life before and during those times, shining a light on the spirited Miep, her story and her place in history in a drama starring Liev Schreiber and Bel Powley — from the team behind Grey’s Anatomy.

“Many people know the story of what happened inside the annex from Anne’s diary, but what was happening outside, Miep and Jan were hiding other people in and around Amsterdam,” co-creator Joan Rater tells The Independent. “So there’s this coming of age story on one side of the bookcase, and there’s another coming of age story on the other side.”

Miep Gies was born Hermine Santruschitz on 15 February 1909 in Vienna, where she lived with her family until she was about 11. Then, sickly and undernourished after food shortages during the First World War, she was sent to live with a foster family in the Netherlands — and never moved back. “Miep” became her nickname, she quickly learned Dutch, she enjoyed life with her foster family and the Netherlands became her home.

Miep was spunky, stylish and trendy, happily reporting in her autobiography Anne Frank Remembered — cowritten with Ms Gold — that she was one of the first girls in Amsterdam to learn the Charleston.

“She was a liver; she loved to live,” says Ms Gold, who became a close friend of Miep and Jan as they toiled together over the book. “She was pretty. She was doing the best she could in a hard time to try to earn a living. She loved the Netherlands. I mean, she was young and and acted young ... she was kind of a live wire, and she even was at the end of her life.”

Miep was 24 and had been jobless for several months — after losing her office position at a textile company in 1933 at a time of high unemployment and uncertainty — when she heard about a possible opening at Mr Frank’s company. She writes about her “freshly washed and ironed skirt and blouse” in Anne Frank Remembered, determined to make a good impression on her prospective employer.

She did. They particularly bonded over the German language, which Miep had grown up speaking in Austria and which was Mr Frank’s native tongue. He had just moved to Amsterdam from Frankfurt and his wife, Edith, and daughters, Anne and Margot, had yet to join him. Mr Frank hired Miep for office work, first insisting that she learn to make jam to expertly answer calls from desperate housewives having trouble with the products.

That meeting would not only change Miep’s life, but also help her to save others.

She’d worked for Mr Frank for nearly a decade — and had become friendly with his family, accepting home dinner invitations with her future husband, Jan — when the ever-deteriorating situation for Jews forced him to ask her a favour like no other.

“I don’t know exactly how they’re going to do it in this series, but when Otto Frank asked Miep to help ... she just says yes, period,” Ms Gold tells The Independent. “I mean, knowing [Miep and Jan], once I got to know them, you believe that. And one of the things that was the most beautiful to me, in a way, about the whole thing, was: This was about friendships.

“I mean, yes, [Miep and Jan] were political; they were left wing,” she says. “They were socialists and anti-Hitler and all that, but ... before the war, they weren’t really involved. He was a social worker. But they were not really political. And this was just about their friends.”

Miep, still an Austrian citizen, had married the Dutchman the year before the Franks went into hiding in secret rooms within the Opekta office building. An adolescent Anne Frank had found their courtship and wedding fiercely romantic; she was 20 years and four months younger than Miep. The young diarist and her fellow fugitives looked to Miep for not only food and protection but also news of the outside world — and anything to break the terrified monotony.

All the time, Miep, Jan and others were attempting to avoid arousing suspicion as they hid their friends and conducted other covert work, the full extent of which may never be known.

“Part of the whole deed that they did, [it] wasn’t just [like] they grabbed somebody who’s about to be hit by a car; this went on for 25 months, day after day after day, that they had to keep that promise,” says Ms Gold, who stayed in Miep’s home on the night Jan died in 1993. “They kept their promise, with all that hardship and danger ... it wasn’t a whimsical, ‘Oh, yes, of course, I’ll help you.’ They really had to put their money where their mouth was.”

Ms Gold met Jan and Miep in the 1980s, first contacting them when she was working in California to appear on a television show. They declined, but “something made me keep their phone number and their address,” she says.

Some time later, when she was considering her next professional move after the television show ended, the couple sprang to her mind.

“I sort of got the sense that, remembering as much history as I remembered about that period, that Miep and Jan, I had no idea they were still alive,” says Ms Gold, now 77. “The war seemed a million years ago. And it occurred to me, they were really old (and ironically, I’m exactly that age) ... it occurred to me, really, that suddenly, somebody needed to tell that story and get them to tell their side of the story. And it was just a little white light moment and that’s sort of how the door inched open a little bit.”

She flew to Amsterdam to interview Miep and Jan for an article, and book offers quickly followed. Ms Gold and the couple agreed to collaborate on the book — which seems to somehow still surprise the author to this day, since she was a veritable stranger — and, in the process, became very close friends. The American mother-of-one was drawn into their meticulous Dutch routine, listening in awe as they recounted incredible events with unruffled stoicism.

“They kept saying, you know, ‘We did nothing. There’s so many people who did much more,’” Ms Gold says.

It’s undeniable, however, that Miep, Jan and others in their close circle risked their lives — and went above and beyond — over and over amidst the constant dangers of Nazi-occupied Amsterdam.

“She had to find food; she had to feed these people,” says Ms Gold, pointing out a challenge that was nearly insurmountable as Nazi soldiers and eagle-eyed spies suspiciously surveyed food purchases. Miep, a married but still childless woman, had to secure enough provisions to sustain eight people in addition to herself and Jan — who was busy with other underground work, as well.

“They had ration cards because of him,” she says. “He brought books from the library, he visited the hiding place every day and went up and kept them company because they were lonely. He found [a] hiding place for the landlady” and others.

Ms Gold says that Jan was “like a double trouble, because you don’t even know what else he did — and you’ll never know ... he was too modest to even tell anyone much of anything.”

The couple’s only son, Paul Gies, died last year; his widow and children remain committed to preserving their grandparents’ legacy. So is Ms Gold, who chronicled her close and unexpected relationship with Miep and Jan in her book Found and Lost: Mittens, Miep and Shovelfuls of Dirt.

She believes the couple “would be very touched” by the new series and continued interest in the story of their lives, the Franks and the others they helped.

“There are courses in universities on the altruistic personality, and she’s sort of a classic of someone who has received human kindness and gave it later,” Ms Gold tells The Independent.

In an afterword for Anne Frank Remembered titled “My 100th Birthday,” Miep addressed the importance of her legacy and that of the others involved in the annex secrecy.

“Despite our age, Jan and I did what was asked of us after the book was published,” she wrote. “We travelled to many countries and met many Holocaust survivors. When we met with school children in Germany and Austria, some of whom were descendants of Nazis, some said to us, ‘Our parents won’t talk about what happened in the war. Our grandparents won’t either. Please tell us what happened.’

“Because I could speak to them in German, and because I was originally from Vienna — in other words, because I was one of them and not an outsider — I was able to tell them the true story of what happened. I could and did tell details that their parents and grandparents had chosen not to discuss with them.”

“It was at this moment that Jan and I were truly glad that we had let Alison persuade us to tell our story,” the Dutch centenarian continued. “We realised that telling the truth of what happened from our perspective was necessary, and that speaking with these schoolchildren was the last important task of our lives.”

The team behind the new Disney+ series, too, say they felt “huge responsibility” when creating the show.

“These are people we admire,” says Ms Rater, who worked on the series with her husband, Tony Phelan, and director Susanna Fogel. “These are people that the world knows; this is tragedy. So all of that, we feel huge responsibility to honor these people, to tell their stories well, to do right by them.”

Quite a bit of that involves continuing to ensure that younger generations learn — and remember — the story of what happened not only around the Amsterdam annex but also the Holocaust in general.

“Our daughter watched parts of the series, and she kept saying, ‘Did this really happen? Did this really happen?’ She couldn’t believe it,” Ms Rater says of her 20-year-old. “And so we want to keep sharing the story.”

Her husband, Mr Phelan, chimes in, highlighting “the fact that Miep did these small acts of kindness. I mean, she was shopping for them, she was bringing them food, she was bringing the medicine, she was also their emotional support. She was their only source of news ... but all of her actions are not so totally out of our everyday experience that make her remote.

“All three of us firmly believe that the inspiration in this story — and Miep made a lot of this herself — is that she is so ordinary, and that anyone can do this.”

When asked what she’d want people to learn from and remember about her friend Miep, Ms Gold addresses that very same point.

Miep proved that it’s possible, she says, “to stick your neck out ... that it’s admirable to have the guts to stick your neck out — and in a modest way to not make a show about courage — and that friendship is worth risking your life for, when your friends are in trouble.

“I mean, that’s really what they both said over and over,” Ms Gold says of Miep and her husband: “‘Our friends were in trouble.’”