This article is part of The Conversation’s series looking at Labor’s jobs summit. Read the other articles in the series here.

With the Albanese government facing difficult challenges on many fronts in the lead-up to the summit, one decision should be straightforward.

It’s axing the so-called Business Investment and Innovation Program, which offers permanent visas to migrants that establish businesses or invest in Australia.

The Business Investment and Innovation Program is one of a number of programs offered in the skilled stream, along with employer-sponsored visas, skilled independent visas, state and territory nominated visas, and global talent and distinguished talent visas.

It accounted for one in seven of the 79,620 skilled visas issued during 2021-22.

Investment is a visa condition

To be accepted, an applicant needs to meet conditions including a minimum level of wealth and a desire to invest in Australia, including by managing a business you own.

Yet we find few of these people finance projects that would not otherwise occur, or provide entrepreneurial acumen that would not otherwise be available.

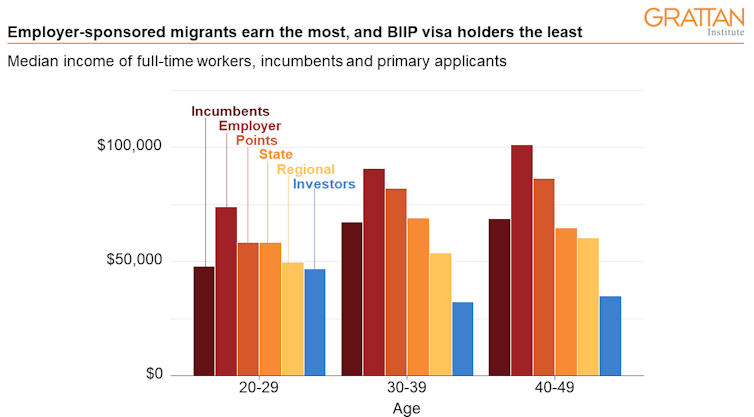

Instead, the Grattan Institute finds people who get a business investment visa tend to earn very low incomes in Australia, costing the government more in payments and public services than they pay it in taxes.

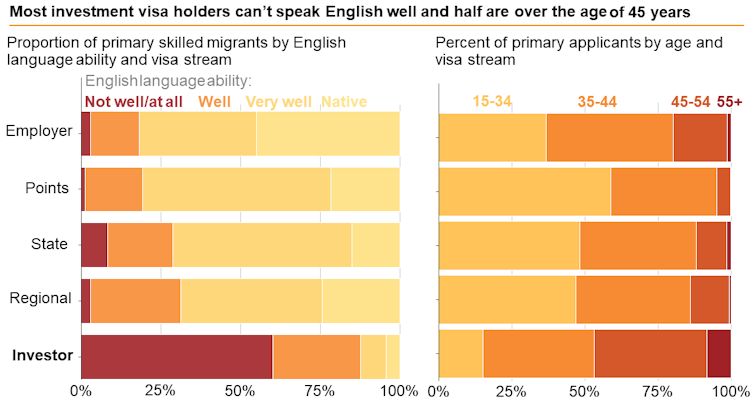

They tend to be older, which means they spend fewer years in the workforce (or in business) before they retire, and therefore pay tax for fewer years before they begin to draw heavily on government-provided services.

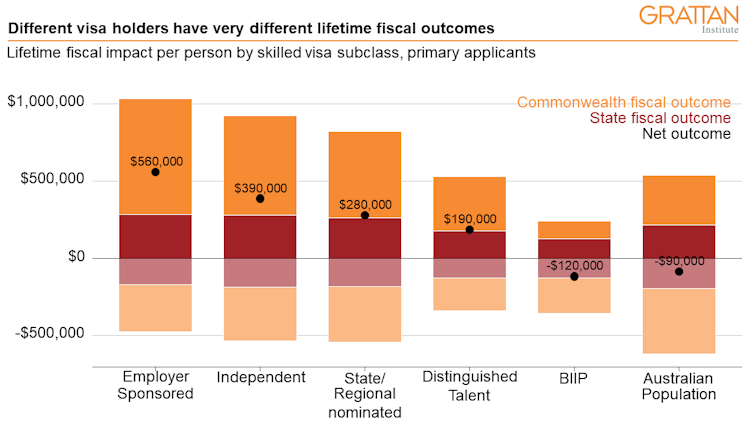

Australian Treasury calculations suggest a business investment visa holder will cost Australian taxpayers $120,000 more in public services than they pay in taxes over their lifetimes.

That compares to an average positive dividend of $198,000 over the lifetime of other skilled migrants.

Only one in ten hold a postgraduate qualification, compared to one in three other recent skilled visa holders. Less than half have a university degree, compared to 80% of other skilled visa holders.

And they generally have lower proficiency in English, which makes it difficult for them to play meaningful managerial roles in growing businesses in Australia.

Little investment

While investment is important for economic growth, there is little sign these visa holders finance projects that would not otherwise occur.

Most business investment visas are not allocated under the “significant investor” stream which requires visa holders to invest at least A$5 million in Australia. Instead, seven out of ten are issued under the “innovation” stream that requires personal wealth of at least $1.25 million and owning a stake in a business with annual turnover of $750,000.

These assets are typically small businesses in retail and accommodation and food services, industries that not likely to assist the stated goal of the program, which is to boost innovation.

Little innovation

The cost of allocating scarce permanent skilled visas to business investment applicants is high: each visa granted through the business investment program is one less visa granted to a skilled worker who could typically be expected to make a larger contribution to the Australian community over their lifetime.

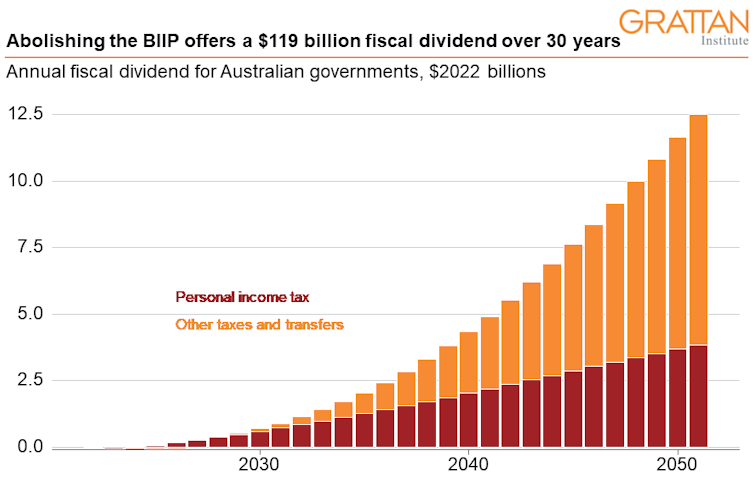

Abolishing the business visa, and reallocating its places to other skilled worker applicants would on our estimate boost the fiscal dividend from Australia’s skilled migration program by A$3 billion over the next decade, and by $119 billion (in today’s dollars) over the next 30 years.

The growing saving is driven by the fact that business investment visa holders retire up to 20 years earlier than other skilled migrants and pay less tax and draw on more health, aged care and pension benefits.

Unlike most other changes that would boost the budget bottom line, axing the business investment visa would not require legislation.

The government should act soon. There’s already a wait list of over 30,000 for the business visa. Just clearing it would cost budgets $38 billion in today’s dollars over three decades.

Economists are fond of saying there’s no such thing as a free lunch. We reckon abolishing the business investment visa is a $119 billion free lunch, waiting for the government to tuck into it.

Grattan Institute began with contributions to its endowment of $15 million from each of the Federal and Victorian Governments, $4 million from BHP Billiton, and $1 million from NAB. In order to safeguard its independence, Grattan Institute's board controls this endowment. The funds are invested and contribute to funding Grattan Institute's activities. Grattan Institute also receives funding from corporates, foundations, and individuals to support its general activities, as disclosed on its website. We would also like to thank the Scanlon Foundation for its generous support of this project.

Tyler Reysenbach does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.