It was around dusk and Kalicharan had just settled down to have his lunch after a tiring day in the agricultural fields in Srisailam when he received the call. The voice on the other end had a sense of urgency and urged him to rush to a spot about a kilometre from Kalicharan’s place. Prepared for a long night ahead, he reached the location within minutes. Before him was an adult python trapped in a borewell pipe in a house. It took over nine hours of wait for Kalicharan to rescue the python, which was later released in the forests of Nagarjunasagar Srisailam Tiger Reserve (NSTR) under the presence of the forest officials.

Kalicharan is one of the four snake rescuers trained by conservation organisations like the Eastern Ghats Wildlife Society (EGWS) in collaboration with the Andhra Pradesh Forest Department to address human-snake conflict in the complex geographical terrain of NSTR. The project of training the locals in snake rescue operations and capacity building workshops initiated by the forest department was kickstarted six months ago. “Every day, we rescue nearly five snakes from the fringe villages in NSTR. On an average, more than 90 snakes are rescued in a month,” says Vignesh Appavu, Divisional Forest Officer, Markapur.

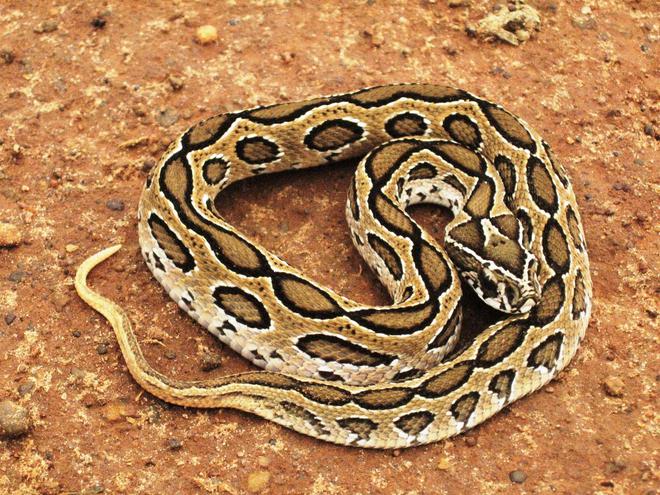

The largest tiger reserve in India, NSTR encompasses an area of 3,568.09 sq. kilometres in the Nallamala hill ranges of Andhra Pradesh. The landscape hosts a breathtaking stretch of thick forest and incredibly rich wildlife. Here, the Bengal tiger shares its habitat with more than 60 species of reptiles, including an array of snakes. These reptiles are unique in many ways: they have no eyelids, no external ears, no limbs and sense their surroundings using their tongue. The forest also has the ‘Big Four’ species of venomous snakes — Russell’s viper, common krait, common cobra and the saw scaled viper.

Snakes have always been an object of fear, fascination and superstition. “Throughout evolutionary history, studies have shown that humans and other primates are likely to have an attention bias toward threats such as snakes. Our innate fear stems out of this. But the issue at NSTR is more complex,” says Vignesh. Sunnipenta and Srisailam are twin towns located within the tiger reserve. In Srisailam alone, the livelihood of 6,000 people depends on the Srisailam temple and the forest. Human-snake conflict has become more frequent here. “Until 2008, a major part of NSTR was inaccessible due to naxal issues. Over the years, wildlife protection has improved. But at the same time, human population has grown exponentially. Human habitations have spread in revenue areas of the region which originally used to be inhabited by snakes,” adds Vignesh. Due to rapid expansion of human settlements and land use changes in the fringe villages, human-snake conflict has risen in many areas around the reserve. Snakes enter houses in search of rats and other resources like water and shelter.

When the AP Forest Department was faced with this peculiar problem, they realised the need to sensitise locals and involve them in the rescue operations.

Managing a huge tiger reserve is a herculean task for the forest department. An additional task of dealing with snake conflicts called for a different participatory approach. “Whenever a snake is on the loose, people call snake rescuers engaged by the forest department. These snake rescuers operate in different locations and are trained professionally in snake rescue, rehabilitation and snakebite management,” says Murthy Kantimahanti, founder of Eastern Ghats Wildlife Society, an organisation working closely with the forest department to provide training to the locals.

AP Forest Department and EGWS have shot a documentary film called Snakes of Nallamala in NSTR to showcase how active engagement with the locals has helped mitigate human-animal conflict. “The film was shot at different locations of the tiger reserve covering the forests and landscapes at Pedacheruvu, Pulicheruvu, Naramamidi Cheruvu, Bairluty range, Srisailam and Dornala Road and Gundem among others,” says Murthy. On World Snake Day observed on July 16, the forest department will be releasing the film to showcase the on-going snake conservation work.

Snake are well adaptive and can be found in various habitats of the reserve. They can be arboreal (living on trees), terrestrial (living on land) and aquatic (living in water). “Snakes are one of the most successful living animals in the evolutionary timescale of earth. Not all snakes are venomous. In fact, a majority of them are harmless and non-venomous. Snakes feed on destructive rodents and are also eaten by many other natural predators in the wild. Thus, they are important for a healthy ecosystem. In NSTR, humans and snakes have been coexisting since time immemorial,” says Murthy.

The forest department now wants to replicate the same model in other fringe villages of the reserve forest