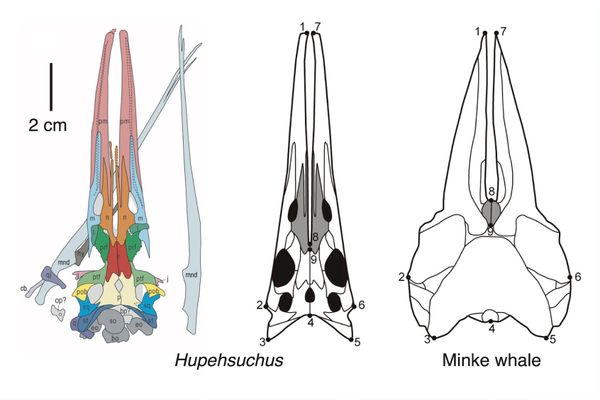

This strange feeding behavior was illuminated in a recent study in the scientific journal BMC Ecology and Evolution. When comparing the skulls of the ancient beast H. nanchangensis with the skulls of baleen whales, a team of Chinese and British researchers realized that the two animals shared similar structures in their mouths. Indeed, this primitive reptile has a lot of anatomical similarities to their highly intelligent cetacean counterparts.

"The snout of Hupehsuchus is highly convergent with modern baleen whales," the study concludes. Yet does that mean that whales are somehow descended from the noble Hupehsuchus? Not exactly.

"There is absolutely no evolutionary link between hupehsuchians and whales!" proclaimed Dr. Michael J. Benton, a co-author of the study from the University of Bristol's School of Earth Sciences. Nonetheless, their study is significant because by drawing these links between the anatomy of an ancient animal and that of one we can study today, scientists ultimately learn more about creatures like the Hupehsuchus. In this case, because we know that baleen whales eat through filter feeding, the study demonstrates that H. nanchangensis did likewise.

While this may seem like a bizarre way to live if you're a human — and are therefore used to enjoying food with two rows of sharp teeth — there is an evolutionary logic to life as a filter feeder.

"Filter feeding is a great way to acquire food because you simply engulf, filter and swallow," Benton told Salon by email. "It only works underwater of course, and only in areas of relatively rich food supply in terms of plankton and small plankton-eaters such as shrimps-krill."

The only real downside to filter feeding is that "the food supply might be seasonal, and could be in low supply at some times of year — but that's true for everything," Benton said.

Hupehsuchus lived on Earth approximately 252 million years ago in what is now China, existing long before whales came on the scene a mere 50 million years ago. The reptile evolved in the shadow of a series of volcanic eruptions that led to so many mass extinctions that the subsequent event was known as "the Great Dying." Although only 5 percent of all Earth's life survived this apocalypse, Hupehsuchus later emerged from that cataclysmic event as one of Earth's more successful creatures. The question of how they flourished, however, revolved around how they were even able to eat. Even though Hupehsuchus first entered the the fossil record around 1972, for more than half a century, these specimens were too incomplete to offer definitive answers on its diet. The new study is based on research of both a complete skeleton and of a clavicle, neck and head.

"When we first saw these specimens, we thought they were very strange," Dr. Long Cheng, an author of the new paper, wrote to The New York Times in an email. "We thought that the snout shape of H. nanchangensis was similar to that in modern baleen whales."

Cheng also noted that the new information about Hupehsuchus could shed light on more iconic animals like dinosaurs. After all, Hupehsuchus exists as a kind of bridge between two worlds — that is, between the ancient lifeforms that roamed the Earth before the Great Dying and the fierce reptiles that did so during the subsequent age of dinosaurs.

"It's been amazing to discover how fast these large marine reptiles came on the scene and entirely changed marine ecosystems of the time," Cheng told the Times.