A brief history of the ABs absolutely caning it , told by one who absolutely caned it

I could do a nifty jug skol back in the day. In that manly, testosterone-fuelled environment, you got kudos for it. I don’t mind admitting I’d feel a bit of pride when I’d overhear people say: "Man, did you see Zarg do that jug?" It became part of who I was. I was the young guy who proved himself by being able to drink like a fish and turn up to training the next day and out-train everybody. I had this thing where I liked proving to teammates that I could push through and could shake off whatever dust I’d collected the night before.

The approval I was getting convinced me this was a path worth pursuing. And it wasn’t difficult. Otago had a Speight’s liaison officer who travelled with the team. His job was to make sure that every town we went to we could find either a Speight’s bar or a bar serving it, so we kept the team’s major sponsor happy. The brainwashing worked on us. Speight’s was a Lion Breweries product, so anything made by Dominion Breweries became known as the Devil’s Urine. The lines could become a little blurred when you travelled to Australia, for instance, where Lion had the licence for Heineken, but DB had it in New Zealand. The consequences were dire if you were caught drinking Devil’s Urine, because the only way to rid it from your body was via a purge. That basically involved skolling as many jugs as it took for you to chunder. If the vomit was not deemed to be of acceptable volume, you would have to keep going. Only then could you claim to have been exorcised and admitted to a church (a Speight’s pub) again.

For home games, you’d shower up and there were always a few beers in the sheds. Then we’d hit the supporters’ club and do the rounds there, drinking and listening to the speeches. Then the call would be made to go back to the changing sheds, where we’d wheel out a keg and enjoy a court session. You didn’t have to have played badly or done anything notably foolish to cop a fine. Any player who was on the cover of the programme would have to do a jug. It was a lot of fun, and if you split a keg between 30-odd players and 10 coaching and management staff, it was basically a jug each. We’d drain the keg and head into town, before turning up for a well-named recovery session the following morning.

It was a curious time in rugby’s history. We were getting paid to play but we still carried over many of the amateur traditions. There was this transition period and I was smack bang in the middle of it at Otago. I embraced that Southern Man ethos as espoused in the Speight’s ads. I was the real-life embodiment of it with my farming background, big frame and scruffy beard. My behaviour fitted that cliché, too. I remember a commentator once describing me as "looking like I’d just emerged from the Catlins, where I’d been feeding on possum".

At the Highlanders, coach Peter Sloane thought it’d be a great idea to bring a breathalyser to the recovery session following games. He did it with the best of intentions, to try to get us to ease back on the post-match celebrations, to demonstrate how a big night was still affecting your sobriety the following day. Instead, we soon corrupted it for our own ends. It quickly became a challenge to see who could blow over 1000 micrograms. That was when the machine gave up. You’d get all these players lining up and if the player blew 1000 there’d be cheers and if you finished short the place would bring out in boos. I don’t think it pleased the management that much, but that was our attitude to anybody trying to inhibit our post-match revelry.

Eroni Clarke came down to the Highlanders for a season in 2002 and I remember him telling me he couldn’t believe what he was seeing. He’d played with guys who were no shrinking wallflowers on the drink at Auckland and the Blues, but he reckoned that what he encountered in Dunedin was next-level. You’d think it would be a bit embarrassing to hear that, especially coming from somebody who had been a big part of winning teams in Auckland and knew how a high-performance environment should work, but no. It mostly felt like a badge of honour.

As young footy players with a bit of cash at hand, we were swept up in that maelstrom and it was a rewarding time. When I got a bit of money coming in, I bought a house in St Clair, a beachside suburb in Dunedin’s south, across the road from the surf club on Victoria Road. Three of the team came to live with me. We decided we were going to get into home brewing and got pretty serious about it. Even in summer we had the fires going in the lounge to keep the room temperature at optimum level. We made more quart bottles of the stuff than we could count. Anton Oliver was recovering from an injury — it might have been his Achilles — and dropped around to my place for a brew. He was obviously impressed and told the rest of the boys that he felt it had some medicinal properties and that was all we needed for the place to turn into what was known as the Victoria Tavern.

We ended up proudly taking crates of the stuff in for a team court session and joked that we wanted to move in on Speight’s territory. If memory serves me, everybody was meant to do a jug skol, but the crates had been shaken up in transit and it was a fairly cloudy, uninviting soup that we were forcing people to drink. With hazy ales being all the rage these days, I suppose you could say we were craft brewers ahead of our time.

It was only once Ted Henry came in at the All Blacks in 2004 that I really experienced any moderation of the drinking culture. There was a consensus that our attitudes to alcohol and to recovery had to change. Guys heading out in cliques looking for a good night had been replaced by more organised team events by the social committee. Ali Williams was known as a fine lock outside the team, but inside the squad he was better known as the guy who could unlock the doors to pubs and clubs in Auckland where we could relax as a team. Partners and wives started to become more involved, which might have been anathema to previous generations, but was actually a really positive development. Young men aren’t great at talking amongst themselves about things beyond the footy field, but in this more inclusive, family environment, you actually got to know your teammates and the things that were important to them.

I talked to Andrew Hore about this once when I had left for Europe and he had stayed on in New Zealand for another World Cup cycle. When we were cutting our teeth in footy, those who didn’t drink or even those who did have a couple of beers but never got drunk were in the absolute minority. If you were on tour anywhere, domestically or overseas, and wanted to find a teammate or two to go and grab a beer with, it was never difficult. He was telling me that by the time he finished his career, it was almost the opposite. The young players coming through hadn’t been exposed to that clubrooms’ drinking culture that used to govern the game.

That’s a good thing, I think, but it was too late for me.

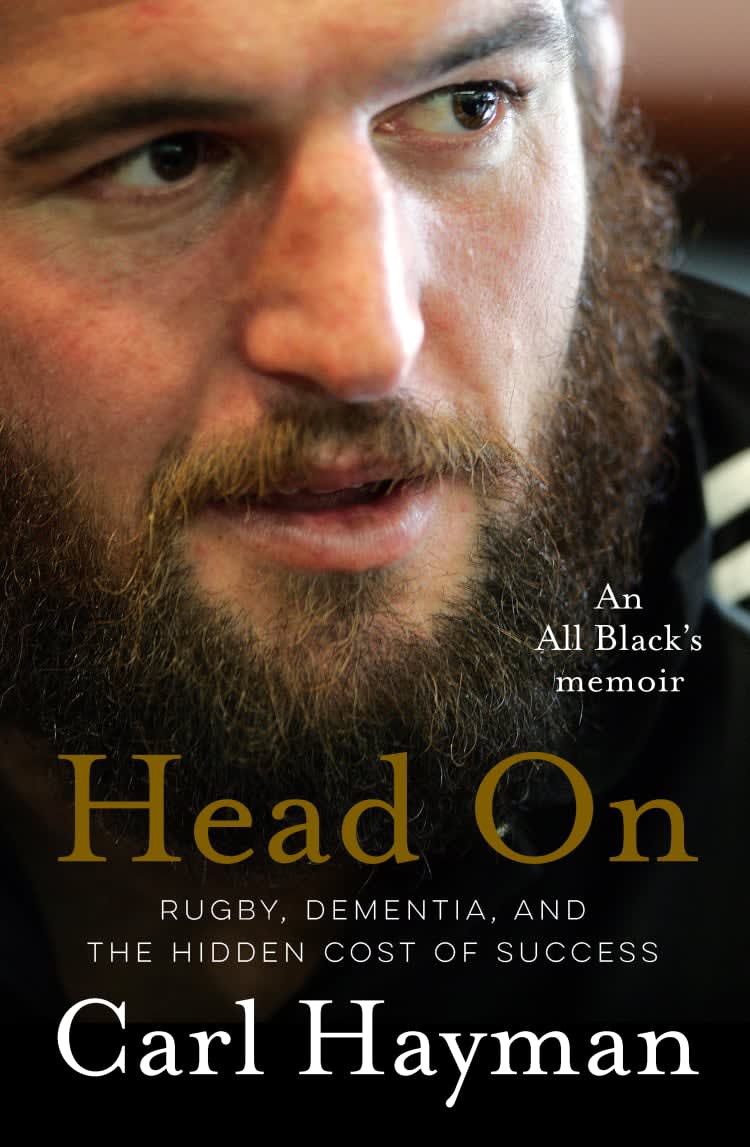

A mildly abbreviated extract taken with kind permission from the new number-one bestseller Head On: Rugby, Dementia and the Hidden Cost of Success by Carl Hayman & Dylan Cleaver (HarperCollins, $39.99)