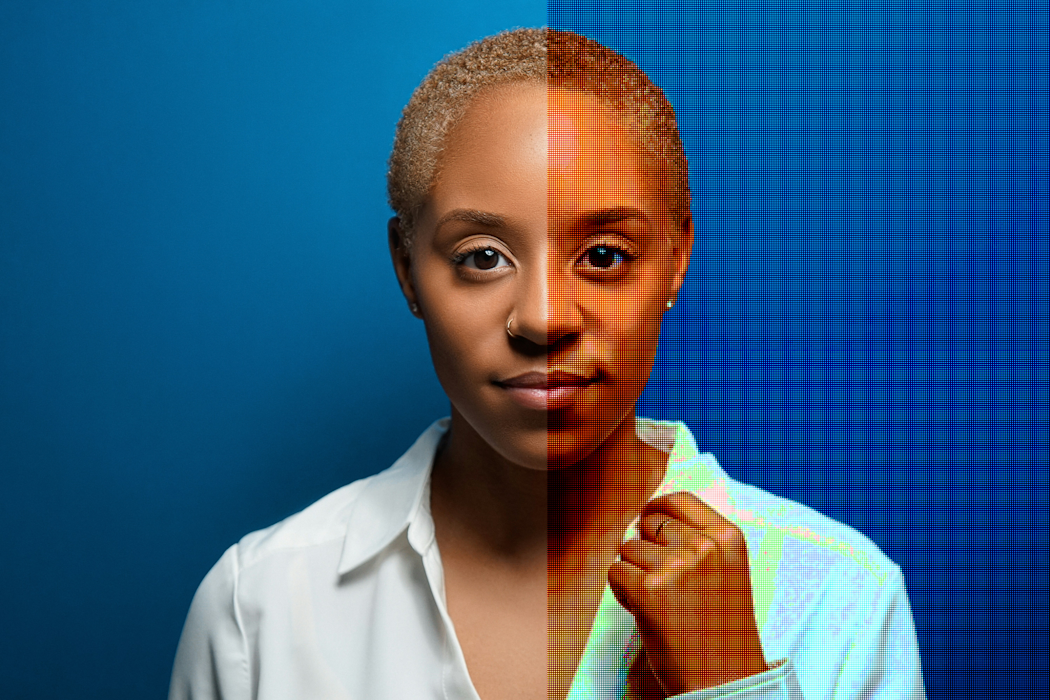

Would you create an interactive “digital twin” of yourself that can communicate with loved ones after your death?

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) has made it possible to seemingly resurrect the dead. So-called griefbots or deathbots – an AI-generated voice, video avatar or text-based chatbot trained on the data of a deceased person – proliferate in the booming digital afterlife industry, also known as grief tech.

Deathbots are usually created by the bereaved, often as part of the grieving process. But there are also services that allow you to create a digital twin of yourself while you’re still alive. So why not create one for when you’re gone?

As with any application of new technology, the idea of such digital immortality raises many legal questions – and most of them don’t have a clear answer.

Your AI afterlife

To create an AI digital twin of yourself, you can sign up for a service that provides this feature, and answer a series of questions to provide data about who you are. You also record stories, memories and thoughts in your own voice. You might also upload your visual likeness in the form of images or video.

The AI software then creates a digital replica based on that training data. After you die and the company is notified of your death, your loved ones can interact with your digital twin.

But in doing this, you’re also delegating agency to a company to create a digital AI simulation of yourself after death.

From the get go, this is different to using AI to “resurrect” a dead person who can’t consent to this. Instead, a living person is essentially licensing data about themselves to an AI afterlife company before they’ve died. They’re engaging in a deliberate, contractual creation of AI-generated data for posthumous use.

However, there are many unanswered questions. What about copyright? What about your privacy?. What happens if the technology becomes outdated or the business closes? Does the data get sold on? Does the digital twin also “die”, and what effect does this have for a second time on the bereaved?

What does the law say?

Currently, Australian law doesn’t protect a person’s identity, voice, presence, values or personality as such. In contrast to the United States, Australians don’t have a general publicity or personality right. This means, for an Australian citizen, there’s currently no legal right for you to own or control your identity – the use of your voice, image or likeness.

In short, the law doesn’t recognise a proprietary right in most of the unique things that make you “you”.

Under copyright law, the concept of your presence or self is abstract, much like an idea is. Copyright doesn’t offer protection for “your presence” or “the self” as such. That’s because there has to be material form in specific categories of works for copyright to exist: these are tangible things, such as books or photos.

However, typed responses or the voice recordings submitted to the AI for training are material. This means the data used to train the AI to create your digital twin would likely be protectable. But fully autonomous AI generated output is unlikely to have any copyright attached to it. Under current Australian law, it would likely be considered authorless because it didn’t originate from the “independent intellectual effort” of a human, but from a machine.

Moral rights in copyright protect a creator’s reputation against false attribution and against derogatory treatment of their work. However, they wouldn’t apply to a digital twin. This is because moral rights attach to actual works created by a human author, not any AI-generated output.

So where does that leave your digital twin? Although it’s unlikely copyright applies to AI-generated output, in their terms and conditions companies may assert ownership of the AI-generated data, users may be granted rights in outputs, or the company may reserve extensive reuse rights. It’s something to look out for.

There are ethical risks, too

Using AI to make digital copies of people – living or dead – also raises ethical risks. For example, even though the training data for your digital twin might be locked upon your death, others will be accessing it in the future by interacting with it. What happens if the technology misrepresents the deceased person’s morals and ethics?

As AI is usually probabilistic and based on algorithms, there may be risk of creep or distortion, where the responses drift over time. The deathbot could lose its resemblance to the original person. It’s not clear what recourse the bereaved may have if this happens.

AI-enabled deathbots and digital twins can help people grieve, but the effects so far are largely anecdotal – more study is needed. At the same time, there’s potential for bereaved relatives to form a dependence on the AI version of their loved one, rather than processing their grief in a healthier way. If the outputs of AI-powered grief tech cause distress, how can this be managed, and who will be held responsible?

The current state of the law clearly shows more regulation is needed in this burgeoning grief tech industry. Even if you consent to the use of your data for an AI digital twin after you die, it’s difficult to anticipate new technologies changing how your data is used in the future.

For now, it’s important to always read the terms and conditions if you decide to create a digital afterlife for yourself. After all, you are bound by the contract you sign.

Wellett Potter is a member of the Copyright Society of Australia and the Asia-Pacific Copyright Association.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.