Russell B. Balikian & Cody M. Poplin (Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP) just filed this brief [UPDATE: link added] on my behalf Friday; they drafted it based generally on some thoughts that I'd expressed in this 2021 Tablet article. Here's the substance of the brief, in case any of you folks are interested:

INTRODUCTION

The First Amendment likely tolerates narrow and clearly defined bans on disseminating knowing lies regarding election procedures—that is, false statements of fact (not opinion, humor, parody, hyperbole, or the like) made with actual malice regarding the time or place of an election, or the procedures one must follow to lawfully cast a valid vote. But Congress has not enacted any federal law that clearly criminalizes such conduct. While some states have passed legislation that comes close to the mark, Congress has debated and repeatedly failed to enact similar statutes. See infra, at 12-13.

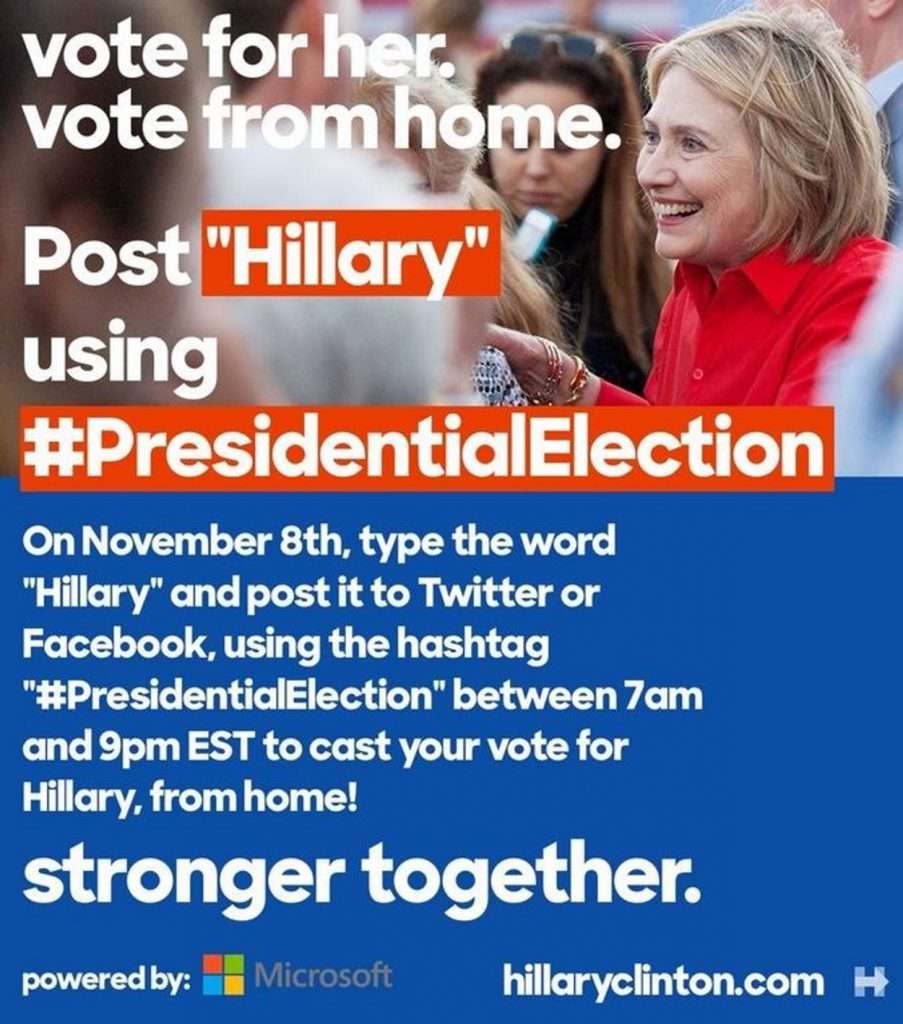

Despite the absence of a federal statute specifically on point, the government prosecuted Douglass Mackey for posting messages on Twitter relating to the 2016 presidential election. To achieve that result, the government repurposed 18 U.S.C. § 241, a statute enacted in 1870 to target violence and intimidation by the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction. United States v. Price, 383 U.S. 787, 800-05 (1966). Section 241 does not specifically address false factual statements about the mechanics of voting, or even speech about elections. Instead, it broadly prohibits "conspir[ing] to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person … in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States." The district court nonetheless construed the term "injure" to encompass any "conduct that makes exercising the right to vote more difficult, or in some way prevents voters from exercising their right to vote." United States v. Mackey, 652 F. Supp. 3d 309, 337 (E.D.N.Y. 2023). It held that Mackey had "fair warning" that this 1870 statute prohibited posting tweets suggesting that people could "vote by text." Id. at 338, 346.

Whatever one thinks of Mackey's tweets, the district court's broad reading of Section 241 brings the statute into conflict with the First Amendment and risks chilling protected political speech. Courts are rightfully loath to let the government regulate the rough and tumble of speech surrounding elections as a general matter, preferring counterspeech as the appropriate remedy. Consistent with that principle, courts in recent years have invalidated broad election-lie statutes in North Carolina, Ohio, Minnesota, and Massachusetts, holding that they are insufficiently clear and narrow to survive First Amendment scrutiny. See Grimmett v. Freeman, 59 F.4th 689, 692 (4th Cir. 2023); Susan B. Anthony List v. Driehaus, 814 F.3d 466, 476 (6th Cir. 2016); 281 Care Comm. v. Arneson, 766 F.3d 774, 796 (8th Cir. 2014); see also Commonwealth v. Lucas, 34 N.E.3d 1242, 1257 (Mass. 2015). These decisions, read together with the Supreme Court's false-speech jurisprudence in cases such as United States v. Alvarez, 567 U.S. 709 (2012), make clear that a statute prohibiting election misinformation will not survive First Amendment scrutiny unless it is narrowly and clearly limited only to knowing (or perhaps reckless) lies made to confuse voters about easily verifiable facts such as the time or place of voting.

Section 241 does not fit that description. Nothing in its text nor in earlier precedents suggests that it forbids lies while protecting other speech; certainly it is not a narrow, clearly defined statute targeting knowing lies about election mechanics. Accepting the district court's view would dramatically expand Section 241's scope and transform it into a boundless, indeterminate criminal prohibition on any speech that the government (later) deems injurious to constitutional rights. Because the district court's interpretation of Section 241 would render it overbroad and impermissibly vague, the best reading of Section 241—and the one compelled by the First Amendment—is that Section 241 does not reach false speech regarding elections. If Congress desires to regulate knowing lies about election mechanics, it must enact a narrow, clear statute targeting such lies.

ARGUMENT

[I.] The First Amendment Permits Narrow and Clearly Defined Prohibitions on Knowing Lies Regarding the Mechanics of Voting.

[See here for more on this. -EV]

[II.] Section 241 Is Not a Narrow and Clearly Defined Prohibition on Knowing Lies Regarding the Mechanics of Voting.

In this case, the government prosecuted Mackey under 18 U.S.C. § 241. Originally enacted in 1870, see Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, § 6, 16 Stat. 140, 141, that statute as revised makes it a crime for:

two or more persons [to] conspire to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person … in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or because of his having so exercised the same.

18 U.S.C. § 241. Congress enacted the statute as a broad remedy to the KKK's campaign of terror targeting newly freed slaves in the exercise of their constitutional rights following the Civil War. See Price, 383 U.S. at 804‑06; see also 18 U.S.C. § 241 (companion provision prohibiting "two or more persons [from] go[ing] in disguise on the highway, or on the premises of another, with intent to prevent or hinder his free exercise or enjoyment" of federal rights).

Because Section 241's reference to "any right or privilege" "incorporate[s] by reference a large body of potentially evolving federal law," the Supreme Court has read certain limits into the statute to ameliorate otherwise significant vagueness concerns. See, e.g., United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931, 941 (1988). The right at issue must be both "clearly established," United States v. Lanier, 520 U.S. 259, 270-71 (1997), and, if only private individuals are charged, must be one that protects against private interference (rather than having a state-action element), see United States v. Williams, 341 U.S. 70, 77 (1951). Before this case, Section 241 had never been interpreted to prohibit purely deceptive speech—and it certainly had never been applied to deceptive speech by private individuals.

When interpreting criminal statutes, courts must avoid unnecessary "collision[s]" with the First Amendment. United States v. Hansen, 599 U.S. 762, 781 (2023). Here, the district court did the opposite, reading the term "injure" broadly to cover purely deceptive political speech so long as it "makes exercising the right to vote more difficult," or in some way "prevents," "hinder[s]," or "inhibit[s]" "voters from exercising their right to vote." Mackey, 652 F. Supp. 3d at 337-38.

That interpretation conflicts with First Amendment principles in two constitutionally significant ways. First, it renders the statute overbroad, because it would "prohibit[] a substantial amount of protected speech," United States v. Williams, 553 U.S. 285, 292 (2008), sweeping in true speech, false speech deriding government policy, and false speech about history, social science, and the like. And second, it renders Section 241 impermissibly vague because it provides "no principle for determining when" speech will "pass from the safe harbor … to the forbidden." Gentile v. State Bar of Nev., 501 U.S. 1030, 1049 (1991). Accordingly, because Section 241 is not a narrow statute that forbids clearly defined knowing lies about the time or place (or other technical mechanics) of voting, the better reading is that the term "injure" does not encompass false—as opposed to coercive—speech that injures people's right to vote.

[A.] The District Court's Interpretation of Section 241 Would Render It Unconstitutionally Overbroad

Courts have regularly invalidated statutes that are "substantially overbroad," Stevens, 559 U.S. at 842, or that are insufficiently tailored to their ends, Alvarez, 567 U.S. at 737-38 (Breyer, J.). A statute, like Section 241 as interpreted by the district court, that imposes criminal penalties on speech is "especially" likely to be found overbroad. Virginia v. Hicks, 539 U.S. 113, 119 (2003). Here, the district court's interpretation of Section 241 sweeps in a substantial amount of protected speech regarding the right to vote and other rights, and lacks the necessary limiting features of other criminal statutes prohibiting knowingly false speech.

To begin, the district court's expansive reading of Section 241 encompasses any speech that purportedly "obstructs," "hinders," "prevents," "frustrates," "makes difficult," or "inhibit[s]" other persons' exercise of voting rights. Mackey, 652 F. Supp. 3d at 336-38 (quotation marks and brackets omitted). This standard is not limited to threatening speech at the voting booth: "[Section] 241 could be violated at any stage that represent[s] an integral part of the procedure for the popular choice," and "in any way that injure[s] [the] right to participate in that choice." Id. at 334 (quotation marks omitted).

That interpretation sweeps in a host of clearly protected speech. It would, for instance, forbid true speech simply because it suppresses voter turnout and thus "prevents" or "inhibits" people from voting. See McIntyre, 514 U.S. at 343-44 (striking down regulation that "applie[d] even when there is no hint of falsity or libel"); Grimmet, 59 F.4th at 692-93 (First Amendment "forbids" criminalizing true speech). A campaign's decision to trumpet news articles explaining why many eligible voters will decline to vote could thus be criminal if it is intended to reduce voting by the campaign's opponents. See, e.g., Sabrina Tavernise & Robert Gebeloff, They Did Not Vote in 2016. Why They Plan to Skip the Election Again, N.Y. Times (Oct. 26, 2020); Sabrina Tavernise, Planning to Vote in the November Election? Why Most Americans Probably Won't, N.Y. Times (Oct. 3, 2018). Even the publication of lopsided opinion polls could be a crime, because "when polls reveal more unequal levels of support, turnout is lower with than without this information," see Jens Großer & Arthur Schram, Public Opinion Polls, Voter Turnout, and Welfare: An Experimental Study, 54 Am. J. Pol. Sci. 700, 700 (2010), which is to say that some voters are "inhibit[ed]" from voting.

Other types of protected speech would similarly be swept into Section 241's scope. Under the district court's reading, peaceful picketing outside a political party's headquarters would be covered by Section 241, since it is designed to "inhibit" people from voting for particular candidates. So too would unsubstantiated claims that the opposing candidate is a crook or a racist, which could be deemed misleading information that "obstruct[s]" or "hinder[s]" people's right to vote by tricking them out of voting for their preferred candidate. Urging a company, school, or other organization to curtail its get-out-the-vote effort and focus on other priorities is also a form of advocacy protected by the First Amendment, but it could be criminalized as speech published "with the specific intent to … prevent qualified persons from exercising the right to vote," United States v. Tobin, 2005 WL 3199672, a *3 (D.N.H. Nov. 30, 2005), so long as the district court's broad reading of Section 241 is accepted.

The district court's view of Section 241 would even sweep in the "Please I.D. Me." buttons at issue in Mansky, which Minnesota argued "were properly banned because [they] were designed to confuse other voters about whether they needed photo identification to vote." 138 S. Ct. at 1884, 1889 n.4. The statute there was much narrower than Section 241, since it was limited solely to speech at polling places (which are nonpublic fora) on election days; but a 7-2 majority of the Supreme Court nevertheless concluded that a law barring "political" apparel in such places still was far too "indeterminate" and primed with "opportunity for abuse" to survive constitutional scrutiny. Id. at 1891. Under the district court's view of Section 241, however, the government could regulate any speech that "hinders," "frustrates," or "inhibits" voting—in any location, and at any time.

The district court's interpretation is also likely to chill speech regarding other constitutional rights. Section 241's text is not limited to protecting the right to vote; it prohibits "injur[ing]" people "in the free exercise or enjoyment" of "any right or privilege secured … by the Constitution or laws of the United States." 18 U.S.C. § 241 (emphasis added). Thus, speech that inhibits people in the exercise of other rights could be criminalized. For example, a climate-change activist opposed to air travel could be criminally prosecuted if she publishes misleading statistics about environmental harms associated with flying. See Bray v. Alexandria Women's Health Clinic, 506 U.S. 263, 274 (1993) (the "right to interstate travel" is a right "constitutionally protected against private interference"); see also Hiroko Tabuchi, 'Worse Than Anyone Expected': Air Travel Emissions Vastly Outpace Predictions, N.Y. Times (Sept. 19, 2019). The district court's reading would likewise sweep in the constitutionally protected speech of a civil rights boycott leader who uses the threat of "social ostracism" to discourage black residents from exercising their federally protected right to patronize white-owned stores or restaurants. NAACP v. Clairborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 886, 910, 913 (1982); 42 U.S.C. § 2000a. There is practically no limit to the variety of speech that could be chilled by such an expansive reading.

Finally, Section 241 lacks the limiting features necessary to sustain statutes prohibiting certain categories of false speech. Spanning "almost limitless times and settings," Section 241—as the district court construed it—comes with "no clear limiting principle." See Alvarez, 567 U.S. at 723 (plurality op.). Here, the statement at issue was made on a large social media platform, but the statute would apply "with equal force" no matter the context, and would include barstool comments to new acquaintances about voting at 10 p.m. or on a Wednesday. See id. at 722. Moreover, Section 241, unlike fraud statutes, does not by its terms require a showing of materiality or reliance—only that a conspiracy was formed to make false statements. Other courts have found the lack of such limiting features to undermine the constitutional validity of election-speech regulations. See Lucas, 34 N.E.3d at 1249-50.

Concerns about Section 241's breadth and potential to ban protected speech motivated at least one court of appeals to read Section 241 to reach only speech that threatens or intimidates. See United States v. Lee, 6 F.3d 1297, 1298-99, 1304 (8th Cir. 1993) (en banc) (Gibson, C.J., plurality op.) (rejecting jury instruction that applied Section 241 to speech that "inhibit[s]" or "interfere[s]" with the exercise of rights). As one judge noted in dissenting from the later-reversed panel opinion, "a great deal of speech is sufficiently forceful or offensive to inhibit the free action of persons against whom it is directed, in the sense that it would make someone hesitate before acting in a certain way"; in fact, that "is the very purpose of speech: to influence others' conduct." United States v. Lee, 935 F.2d 952, 959 (8th Cir. 1991) (Arnold, J., dissenting) (emphasis added)). The district court's interpretation in this case raises the same overbreadth concerns.

Here, Congress could substantially achieve its purported objective of ensuring that "voters have accurate information about how, when, and where to vote," Mackey, 652 F. Supp. 3d at 347, through "a more finely tailored statute" that is "less burdensome," Alvarez, 567 U.S. at 737-38 (Breyer, J.); Stevens, 559 U.S. at 481-82 (an overbroad statute is not finely tailored). And the potential misapplications and abuses of reading Section 241 to cover deceptive speech substantially exceed whatever lawful applications may be found. Williams, 553 U.S. at 292. As a result, the district court's interpretation renders Section 241 overbroad.

[B.] Applying Section 241 to Cover Speech Would Render It Unconstitutionally Vague

Section 241 has been described as "the poster child[] for a vagueness campaign." See Hope Clinic v. Ryan, 195 F.3d 857, 866 (7th Cir. 1999), judgment vacated on other grounds by Christensen v. Doyle, 530 U.S. 1271 (2000). Applying it to pure speech only magnifies those already significant vagueness concerns because it is unclear what speech would violate the statute, and whether similar "false speech" would "inhibit" the exercise of other rights.

"When speech is involved," the Constitution demands "rigorous adherence" to the requirements of fair notice, because fear that a vague restriction may apply to one's speech is likely to deter even constitutionally protected speech. See FCC v. Fox Television Stations, Inc., 567 U.S. 239, 253-54 (2012) (courts must "ensure that ambiguity does not chill protected speech"); NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 438 ("precision of regulation must be the touchstone" when determining whether a regulation impedes on First Amendment rights). Where "the law interferes with the right of free speech," courts have required exacting statutory precision. Village of Hoffman Estates v. Flipside, Hoffman Estates, Inc., 455 U.S. 489, 499 (1982); Button, 371 U.S. at 432 ("[S]tandards of permissible statutory vagueness are strict in the area of free expression.").

Here, neither Section 241 "nor a good many of [its] constitutional referents delineate the range of forbidden conduct with particularity." Lanier, 520 U.S. at 265. Section 241 does not define any mental state with respect to a statement's falsehood and is not limited to any particular subject matter. Instead, it refers generally to the Constitution and federal statutes—and court decisions interpreting them—to determine which conspiracies it prohibits. Kozminski, 487 U.S. at 941. Section 241 itself thus offers no "guidelines to govern law enforcement," Kolender v. Lawson, 461 U.S. 352, 358 (1983), in applying the statute to speech. In this regard, Section 241 starkly differs from the state laws discussed above that target specific types of knowing lies about the mechanics of voting. See supra, at 12-13. This lack of "explicit standards" for law enforcement to apply to differentiate between lawful and unlawful speech under Section 241 "invit[es] subjective or discriminatory enforcement." Grayned v. City of Rockford, 408 U.S. 104, 108, 111 (1972).

Even the Department of Justice has previously indicated that "there is no federal criminal statute that directly prohibits" the act of "providing false information to the public … regarding the qualifications to vote, the consequences of voting in connection with citizenship status, the dates or qualifications for absentee voting, the date of an election, the hours for voting, or the correct voting precinct." Dep't of Just., Federal Prosecution of Election Offenses 56 (8th ed. 2017). Here, the government has attempted to read such a restriction into Section 241. But because Section 241 does not "directly" regulate the conduct at issue, see id., the statute cannot provide clarity as to the range of forbidden conduct, let alone with the sort of "precision" that the First Amendment demands, United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258, 265 (1967).

Past prosecutions likewise did not anticipate the government's use of Section 241 in this case. Complaints concerning voter misinformation are almost as old as the Republic itself, see Elaine Kamarck, A Short History of Campaign Dirty Tricks Before Twitter and Facebook, Brookings Inst. (July 11, 2019), yet the government has never utilized Section 241 to punish conduct like Mackey's that involves deceptive—as opposed to coercive or threatening—speech. Indeed, other prosecutions under Section 241 almost invariably involve conduct, not speech.[1] There are thus no court decisions clarifying when deceptive speech in the election context crosses the line from vigorous advocacy to unlawful "injury."

The fact that Section 241's state-action limitation is a judicial gloss only enhances the vagueness problem. See United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745, 754-55 (1966); Williams, 341 U.S. at 77. If a person can be "injured" in the exercise of their rights through pure speech, the statute's plain text suggests that any "two or more persons" could cause that harm. See 18 U.S.C. § 241. The district court's interpretation of the statute thus suggests that purely private speech would violate the statute if it "inhibit[s]," "frustrate[s]," or "obstruct[s]" individuals from exercising rights that otherwise have state-action requirements, such as the First Amendment right to speak, U.S. Const. amend. I, or the Second Amendment right to "keep and bear Arms," U.S. Const. amend. II. For instance, does protesting gun sales in one's town injure people in exercising their rights under the Second Amendment? The statutory text itself does not answer this question, thereby imposing an impermissible and "obvious chilling effect" on speech regarding any number of constitutional rights, see Reno v. ACLU, 521 U.S. 844, 871-72 (1997)—even those rights beyond the power of Congress to protect from private interference.

Nor can this vagueness problem be solved by retroactively limiting Section 241 solely to conspiracies to prevent voting through knowingly false statements about the mechanics of an election. The Court's analysis in Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971), is instructive here. In Cohen, the Court rejected the argument that a disturbing-the-peace statute could constitutionally be applied to wearing a jacket with an offensive message into a courthouse:

Cohen was tried under a statute applicable throughout the entire State. Any attempt to support this conviction on the ground that the statute seeks to preserve an appropriately decorous atmosphere in the courthouse where Cohen was arrested must fail in the absence of any language in the statute that would have put appellant on notice that certain kinds of otherwise permissible speech or conduct would nevertheless, under California law, not be tolerated in certain places. No fair reading of the phrase "offensive conduct" can be said sufficiently to inform the ordinary person that distinctions between certain locations are thereby created.

Id. at 19 (citations omitted).

Likewise, Mackey was tried under a statute that on its face is equally applicable (or inapplicable) to speech, regardless of whether that speech falsely describes the mechanics of voting. As a result, "[a]ny attempt to support [Mackey's] conviction on the ground that" Section 241 targets only a narrow class of false statements "must fail" because the statute contains no limiting language "that would have put [Mackey] on notice that certain kinds of otherwise permissible speech or conduct" that injures a person's exercise of constitutional rights "would nevertheless, under [Section 241], not be tolerated" if it concerns false information about how to vote. See id. "No fair reading" of the statutory phrase "conspir[ing] to injure … any person … in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege," 18 U.S.C. § 241, "can be said sufficiently to inform the ordinary person that distinctions between" false statements about the mechanics of voting and false statements about exercising other federal rights "are thereby created." Cohen, 403 U.S. at 19.

The "government may regulate in the area" of First Amendment freedoms "only with narrow specificity." Button, 371 U.S. at 433. Because Section 241 provides "no principle for determining when" speech has "pass[ed] from the safe harbor … to the forbidden," Gentile, 501 U.S. at 1049, interpreting it to encompass any kind of injurious speech would make it "susceptible of sweeping and improper application," Button, 371 U.S. at 433. As a result, people may well "steer far wide[] of the unlawful zone" and avoid speaking at all. Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360, 372 (1964). The First Amendment does not permit a reading that produces such a result.

CONCLUSION

The First Amendment tolerates narrow, clear statutes that target knowingly false speech concerning the time, place, and manner, or other technical mechanics of an election. But Section 241 is not such a statute. This Court should reverse the decision of the district court.

[1] See, e.g., United States v. Butler, 25 F. Cas. 213, 220 (D.S.C. 1877) (conspiracy to murder a freed slave); United States v. Stone, 188 F. 836, 839, 840 (D. Md. 1911) (printing ballots that made it "impossible" for illiterate voters to vote for Republicans); United States v. Mosely, 238 U.S. 383, 385 (1915) (refusing to count valid ballots); Ryan v. United States, 99 F.2d 864, 866 (8th Cir. 1938) (altering ballots); Crolich v. United States, 196 F.2d 879, 879 (5th Cir. 1952) (forging ballots); United States v. Anderson, 417 U.S. 211, 226 (1974) (casting ballots for fictitious persons); United States v. Haynes, 1992 WL 296782, at *1 (6th Cir. Oct. 15, 1992) (destroying voter registrations); Tobin, 2005 WL 3199672, a *1 (jamming telephone lines to obstruct ride-to-the-polls service).

The post Amicus Brief Related to the Mackey "Vote-by-Text" Meme Prosecution appeared first on Reason.com.