The Los Angeles Rams and the Cincinnati Bengals will battle Sunday evening in the Super Bowl, that once-a-year event when a uniquely American sport becomes a global spectacle.

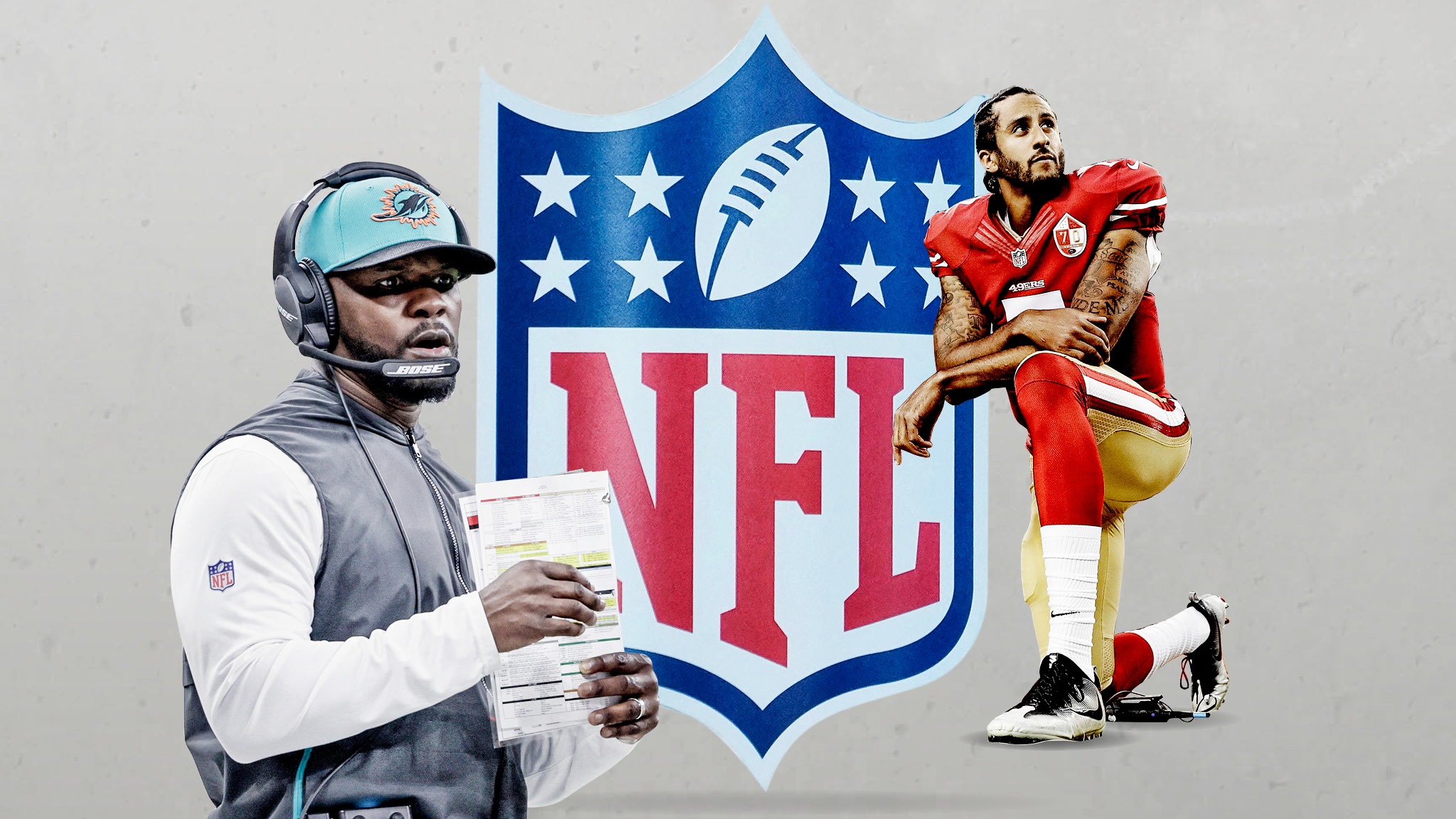

But before they even take the field, American football’s most consequential play in a generation will already have been made. It happened in a New York court when Brian Flores, a former head coach of the Miami Dolphins with seemingly lustrous prospects, filed an incendiary lawsuit against the National Football League and a trio of clubs, accusing them of racial discrimination in their hiring practices.

Flores, who is African American, describes the NFL in his complaint as a “plantation” in which the league’s 32 owners, none of whom are black, profit from a workforce that is about 70 per cent black. “The owners watch the games from atop NFL stadiums in their luxury boxes, while their majority-black workforce put their bodies on the line every Sunday, taking vicious hits and suffering debilitating injuries to their bodies and their brains while the NFL and its owners reap billions of dollars,” the complaint states.

Flores, 40, was a surprise cull last month after leading the Dolphins to consecutive winning seasons. The club attributed his dismissal to the vague category of “poor communication skills”. He was instantly considered a top candidate for one of the eight other clubs seeking a new head coach, including the New York Giants.

According to his 58-page complaint, the Giants co-owner, John Mara, contacted Flores the day after his firing to tell him of the team’s interest, and discuss an interview. Days later, on a Monday, he received a text from his former boss, Bill Belichick, the longtime coach of the New England Patriots, and a man with longstanding ties to the Giants organisation.

“Congrats!!” Belichick wrote Flores, telling him that he had won the job. This surprised Flores since his interview was not until Thursday.

“Coach, are you talking to Brian Flores or Brian Daboll. Just making sure,” Flores wrote back, suspecting that Belichick was mistaken.

“Sorry — I fucked this up,” the coach replied. It was Daboll, a white coach, who was getting the job. “I’m sorry about that. BB.”

Flores went through with the interview even though he was convinced it was a “sham” conducted only to satisfy the NFL’s “Rooney Rule”, which requires clubs to interview at least two minority candidates for a vacant head coaching job. He later described the experience as “humiliating”. Then, after consulting with friends and family, he hired lawyers and filed a suit that has stunned the sport.

The complaint includes the texts from the famously taciturn Belichick as well as allegations that another American football legend, John Elway, a former star player who now runs the Denver Broncos, turned up late and disheveled for a separate “sham” interview with Flores, apparently after a late-night of drinking. Elway denies this.

Flores also claimed that the Dolphins owner, Stephen Ross, the chairman of the Related Companies, one of the largest US property developers, encouraged him to “tank” the 2019 season so the club would finish lower in the rankings and then be among the first to pick players in the upcoming draft of college players. Ross even offered him $100,000 for each game the team lost that year, Flores said — something Ross vehemently denies.

For all the shock that Flores’ lawsuit has provoked, its central contention that the NFL has racist hiring practices is hard to counter. Twenty years after the league instituted the “Rooney Rule” — named for the late owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, Dan Rooney — to improve the diversity of its coaching ranks, it had just one black head coach.

The NFL issued a statement soon after Flores’ suit was filed, dismissing it as “without merit”. But on Saturday, Roger Goodell, its commissioner, shifted the tone in a memo sent to the 32 clubs. While the league had made “significant efforts to promote diversity”, Goodell wrote, “we must acknowledge that particularly with respect to head coaches the results have been unacceptable”.

Richard Lapchick, who was part of the campaign that resulted in the Rooney Rule and is now a professor at the University of Central Florida, says he had become convinced that Goodell wanted change, but was at the mercy of the owners. “By and large, NFL owners are wealthy white men whose political profiles are very conservative,” he says. “And I think that is where the buck finally stops.”

Whether Flores can force change through the courts is unclear. The NFL will probably push for dismissal of the complaint, which seeks class-action status, and a federal judge must then decide whether it can proceed.

Such discrimination cases can be difficult to prove, according to Beth Bloom, an employment lawyer in Seattle. “You’re talking about proving motive and what was in someone’s mind,” she explains. “There can be countless explanations . . . to muddy the waters.”

But the complaint has already succeeded at reinvigorating a discussion about race and leadership in America’s most popular sport, and bringing the plight of black coaches to the forefront. “Win, lose or draw,” says Bloom, “Brian Flores’ case is an important case.”

American football’s reckoning

To some degree, the NFL is struggling with the same racial and social reckoning that has shaken other organisations in recent years, in sports and beyond. In England last year, cricket was engulfed by allegations of institutional racism against British Asian players. The Premier League has struggled to tackle racist abuse of its players, including those who knelt before games in support of Black Lives Matter.

But those social justice protests originated in the NFL, when Colin Kaepernick, then a star player for the San Francisco 49ers, began kneeling during the pre-game playing of the national anthem during the 2016 season in order to call attention to racial injustice and police brutality.

The protest divided locker rooms and then a nation. President Donald Trump responded by urging owners to “fire” those who knelt, complaining it was un-American. Others rallied to Kaepernick’s side, making him a global icon.

The great NFL divide

82%

The share of head coaching jobs in the NFL that went to white men between 2012 and 2021. 84% of general managers, who employ head coaches, were white men.

12

The number of people of colour hired to manage an NFL team’s offence, or its attacking players, between 2012 and 2021. In the same period, 107 white men were hired for such jobs.

13.2%

The share of team professional staff, or entry level and middle management roles held by black people, the highest in NFL history. Of the players, around 71% are black.

Sources: NFL, NBC News, tidesport.org

Kaepernick failed to receive an offer from another team after his contract expired in 2017, and still remains out of American football. He settled a collusion lawsuit against the league and the owners in 2019.

The police murder of George Floyd in 2020 provoked a much broader national discourse over racial discrimination, and the NFL last year stencilled the words “End Racism” on its playing fields and uniforms. But, as the Flores complaint amply recounts, such gestures pale beside a long history of racism in which, like other American institutions, progress has come grudgingly.

A gentleman’s agreement among the owners kept black players out of the league from 1934 to 1946. It was broken when the Rams moved from Cleveland to California and took up residence at the Los Angeles Coliseum. The stadium was publicly funded and so there was an outcry for integration. The club signed two local black players, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode.

Later, the fight moved on to who could play quarterback, the sport’s most glamorous position. In 1968, Eldridge Dickey was the first black college quarterback to be selected in the first round of the NFL draft. But Dickey, a meteoric college talent, was given limited opportunity to actually play quarterback when he joined the Oakland Raiders. He died a tragic figure. His successors would be trailed by racist whispers that they lacked the intellect or the discipline the position required.

Sometimes the racism was not spoken quietly. In 1988, Jimmy “the Greek” Snyder, a prominent television sports commentator, voiced a fear consuming other whites in an infamous monologue about black athletic prowess, which he attributed to breeding practices during slavery. If they “take coaching, as I think everyone wants them to, there is not going to be anything left for the white people”, Snyder said. He was fired by the CBS television network the next day.

The black coaching gap

Even more than its counterpart in other professional sports, the American football coach was long regarded as a modern-day field general or captain of industry, an archetypal leader of men in a complex and brutal contest. More recently, the fraternity has expanded to include a crop of “boy geniuses” who use data and complex offensive schemes, and would seem at home in the tech industry.

The NFL’s first black head coach was Art Shell, a former offensive lineman hired by the Raiders in 1989. By the same year, the National Basketball Association had had more than a dozen black head coaches.

In a pattern that would become familiar to other black coaches, Shell was highly qualified: he had played for 14 years and then spent six years as an assistant coach before getting the top job. Like other black head coaches, he would also be fired following a winning season, and then struggle for another opportunity.

The NFL instituted the Rooney Rule in December 2002 after Johnnie Cochran, the trial lawyer who famously represented OJ Simpson, and civil rights lawyer Cyrus Mehri threatened to sue for discrimination. They came armed with a report they had commissioned from Janice Madden, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania, concluding that black coaches outperformed their white counterparts but still received fewer opportunities.

The number of black head coaches jumped from two in 2002 to seven in 2006, and the Rooney Rule was generally celebrated for giving greater exposure to minority candidates. Under Goodell, the NFL has since expanded the rule, requiring teams to also apply it to executive jobs. The league has also built a database with 5,177 qualified coaches — many from under-represented minorities — to serve as a kind of dating app for NFL teams.

Yet the numbers have again declined in recent years. “I am frankly puzzled about what is now going on,” Madden wrote in an email. “My only thought is that unconscious bias is extremely hard to deal with when selections are ultimately based on ‘gut feelings’ about who will work out, rather than clear standards about qualifications that matter.”

The NFL appointed Jonathan Beane as its first chief diversity and inclusion officer in August 2020, three months after Floyd’s death. He says he has confronted the same issues at the league that he found at the healthcare, media and manufacturing companies where he previously worked. But he says a “lot of progress has been made in a lot of areas”.

The NFL now has a strategic diversity plan that covers each of its departments. It has also implemented smaller changes, from gender-neutral bathrooms to more transparent pay policies and how it selects its vendors.

But there is broad agreement that major changes will not come without the acquiescence of the billionaire team owners who have the power to hire and fire coaches as they see fit. Those owners are overwhelmingly white and old, and tend not to be at the forefront of a changing culture.

“I’ve tried to dream up the rule or the legislation that would change this, and you’ve gone about as far as you can go,” says Kenneth Shropshire, who leads the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University. “It is kind of the oldest story in the world, at least in terms of laws trying to deal with civil rights issues and race. In the end, you cannot make people do something.”

The Rooney Rule did at least succeed in widening the slate of candidates for a potential job, Beane argues. And he points to evidence that clubs are beginning to examine and change their own practices: two teams, the Chicago Bears and Minnesota Vikings, recently included their chief diversity officers in the selection process for new general managers. “I think we need to humble ourselves,” Beane says, “and we also have to have a sense of urgency.”

Besides the result of Sunday’s Super Bowl, many around the league will be watching to see if Eric Bieniemy, the African American offensive co-ordinator of the Kansas City Chiefs, will win one of the remaining vacant head coaching jobs. Bieniemy is widely regarded as one of the NFL’s most qualified candidates but has repeatedly been passed over.

As for Brian Flores, his legacy now supersedes American football but his future in the sport is unclear. Whether he receives another opportunity to lead an NFL team will be a test of how far the league has really progressed on race. “If I had to bet,” says Lapchick, “I’d say it’s a long time before he gets another head coaching job.”

Asked about the risk that he had jeopardised his career, Flores told National Public Radio it was one he was willing to take. “If I never coach again but there’s significant change, it will be worth it,” he said.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022