Every game, you could hear the same sideline rumblings, the same surprised observation: There’s a girl on the other team.

A girl was playing for Total Futbol Academy in MLS Next, the top level of U.S. boys’ talent. Academy programs like this one produced men’s national team stars Weston McKennie and Tyler Adams. Every guy on the field wanted to make it to the pros. And the girl? She’d already made it.

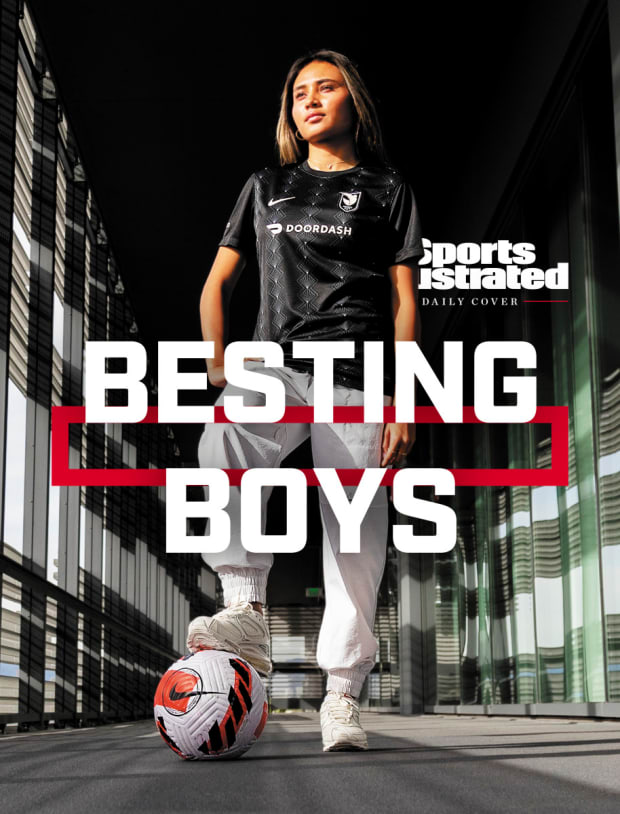

Earlier this year, NWSL’s Angel City FC used the draft’s No. 1 pick on 18-year-old Alyssa Thompson, making her the first player taken straight out of high school. Immediately, GM Angela Hucles described Thompson as “a generational talent”—but even that description fails to capture all that she represents. For many, it’s hard to believe that a girl can compete with the physicality and speed of a top 18-year-old boys’ team. But Thompson doesn’t just keep pace with the boys, she stands out among them. A senior at Harvard-Westlake School in Los Angeles, she is petite (5'3"), strong and track-star fast. When she won the Mission Classic meet last March, she ran the 100m in 11.74 seconds, which clocked out as the second-fastest girls time in California.

Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

“When she breaks away, it’s just like, Ah man, she’s faster than you, just deal with it,” says Mario Gonzalez, TFA director of coaching.

The slogan for MLS Next—which was formed in 2020 and now has 133 clubs across 31 states and Canada—is “The Future Starts Here,” and Thompson, a teenage phenom shaking up the landscape of youth sports, feels like a glimpse ahead.

“To see Alyssa Thompson make it big?” says her TFA teammate Victor Corona. “It drives us. We’re aiming for the top shop—the big leagues. Our dream is the same as hers.”

In a home video taken when Alyssa was 5 or 6, living in Studio City, Calif., she and her younger sister, Gisele, half-frolic, half-dribble across a grassy backyard. Their hair is let down and they’re each wearing a mishmash of soccer gear and little girl clothes—hot pink shorts, purple-striped sweaters, socks covered in hearts, tiny Nike cleats. As Alyssa daintily taps at a ball, hands flapping in front of her, Gisele giggles delightedly in the background. There is no sign here that Alyssa will one day be the first high schooler drafted to the pros, but you can hear her father, Mario, in the background—“Right foot, right foot, Go Alyssa, your turn”—and in his voice is a keen interest, a sense of possibility.

Karen, Alyssa and Gisele’s mom, notes how different that perspective is from that of her own parents’ just a generation earlier. Her mom and dad, Sylvia and Romero, grew up outside Lima, Peru, and sports, Karen says, weren’t a path. “My mom never thought of sports as an opportunity to go anywhere.”

By the time Alyssa was 8 and playing for a girls’ club team, Mario made an observation: If you’re fast, they put you at forward. If someone plays the ball over the top, you run onto it. And while Mario hadn’t grown up playing, he did figure there was more to soccer than that.

Eventually, he got wind of TFA, the dominant Los Angeles-based boys’ club, which every year sends its coaches to train in Barcelona and annually enters its U-12 squad in the Mediterranean International Cup in Costa Brava, Spain, where they compete with youth academy teams representing the best European clubs—Barcelona, Manchester City, AC Milan. (Each year, since 2010, TFA has made it to at least the quarterfinals.)

“I figured: If TFA is the best, I want to see what they’re doing,” says Mario. So, in 2013, he asked if he could bring Alyssa out to training. To which club president Paul Walker replied: “It doesn’t hurt.”

By the end of that first training session, Walker had asked Alyssa to be on the team—and when Mario noted that he had another daughter, Gisele, 13 months younger, she was invited to come, too. Mario says that at his daughters’ previous club he had asked whether his girls could play with the boys, to which he was told: No, “that’s why we have a girls’ program.” But TFA took a different approach. “They told us: ‘If they can help us win, we don’t care if they’re boys or girls.’” Alyssa signed onto the 2004 boys’ team; Gisele joined the ’05 squad.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

TFA’s academy was founded with the goal of making soccer more accessible for young players from the outset: eschewing the typical pay-to-play model, they eliminated the club fee, instead raising money through sponsors and fundraising events. Now, kids come from West Covina, San Fernando Valley and downtown L.A. Most are Latino. (The Thompson sisters are Black, Peruvian, Filipino and Italian.) Luis Cruz, who plays for TFA as well as the U-20 Puerto Rican national team, describes the academy’s draw: “Most of the kids come from nothing—we’re from places where you have to really work for what you want. So, most players have that driving focus, because of where they’re from and the opportunities they’re not given elsewhere.”

“It’s an inner-city culture; not everybody can survive,” says Walker. “And the sisters are an island in a sea of boys.”

For two years, until ’15, the sisters played with the TFA boys before transitioning over to a program with a girls’ academy, Real SoCal, in Los Angeles, so they could have that experience too. Then COVID-19 shut everything down.

The Thompsons went on family runs; the sisters honed skills in their cul-de-sac and played one-on-ones at a local field. But they were hungry for more. In 2020, when Mario heard that TFA had restarted training, he called up Walker again. The sisters rejoined the club and have played there since.

Alyssa and Gisele, of course, are not the first girls to play with boys. Carli Lloyd, a two-time World Cup winner, grew up playing pickup with Turkish men in Delran, N.J.; Allie Long competed in cutthroat immigrant futsal leagues in New York; and Alex Morgan played against guys everywhere from Madrid to Berkeley and still plays against her husband, MLS player Servando Carrasco. Nearly every current national team player trains regularly with men.

But competing in a game in an elite league, on a full-sized field, where getting beat means letting your entire team down? That’s what makes their story unique. The sisters are the first girls to play with an MLS Next academy. (It’s worth noting: When the Thompsons first tried to register fully with MLS Next, they weren’t immediately approved—the system wasn’t set up for girls yet. It took many phone calls and emails before they were greenlit.)

Gonzalez, for one, had never coached girls before. “It was a shocker at first—the guys didn’t want to go hard on them, or pass them the ball, and I had to figure out how to break the ice,” he says. He realized that he had to establish the tone—to teach the boys they should treat them like any other player.

“Alyssa, shoot the freaking ball,” he yelled at the next practice. “You are a forward—your job is to score. Score.”

“Gisele, tackle the player! End the play.”

“Once the boys saw that I was being equal and fair, then they were like: O.K., let’s go,” says Gonzalez.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

On a cold January night at Smith Park, in Pico Rivera, Calif., a coyote trots across a playground at dusk. The floodlights turn on, and TFA players begin to show up, cleats tapping against the sidewalk as they walk to the field.

One side of the grounds butts up against Rosemead Blvd., with La Monarca bakery and Birrieria Jalisco across the street. The other side fans out into two smaller fields, and every TFA team—from the 7-year-olds to the 18-year-olds—shares the space. Watching the little ones is downright dazzling: They can do everything their heroes do—rainbows, Iniestas, Rabonas, elasticos—only, they’re elf-sized.

On the far corner of the turf, the 17- and 18-year-olds lace up flats. The Thompson sisters stand slightly to the left of the group. Alyssa’s face is stoic and reserved; Gisele’s is open and expressive as she low-key listens to the guys, who banter and shove one another.

“Look at those dangly earrings—you look like the type of kid who doesn’t bother showing up to class!” one guy teases another.

“What are you talking about? I’m a scholar,” the other boy shouts back. “Three AP classes, no doubt!”

Gisele tucks her hair behind her ears, faintly smiling.

Yes, both girls say unabashedly, they feel nervous for every practice, every game. (Their mother, Karen, can always tell: “They get fidgety, bright-eyed,” she says.) They shrug, like it’s obvious: The speed of play is extremely fast; they have to play their absolute best.

“When I’m playing with boys, I know I can’t make a mistake,” says Alyssa.

“I don’t want to mess up,” says Gisele, nodding. “I don’t want to be that person in the group to let in a goal.”

That pressure and those nerves—it’s why they’re out here. They want to play in an environment that can challenge them the most.

“I have to prove myself every game, every practice,” says Gisele. “When parents—or any player—see that I’m a girl on a guys’ team, they think it’s weird, so I have to show that I belong here.”

During warmups, the sisters hug the fringes—quiet, visibly shy, hands inside their sleeves—as everyone hits passes and runs short sprints. Next to a tangle of teenage guys, they look light and effortless, nimble and spry.

The guys regularly express awe over their speed: “What do you do to get so fast?”

“Don’t put Gisele behind me—she’ll catch me!”

“I don’t want to be next to Alyssa!”

They play a small-sided, high-paced scrimmage. Gisele’s in the center of a crowded midfield, surrounded by guys. She eliminates all of them with a through ball to the feet of the forward who turns and scores with ease. She repeatedly solves the pressure, maneuvering out of tight spaces, finding the dangerous pass.

“She’s always buzzing around the ball,” says Gonzalez. “She likes contact, likes tackling, doesn’t mind getting in a player’s space.”

Alyssa meanwhile plays like a crouching tiger: in the scrimmage, she has a languid, almost eerie jog, with alert eyes, looking to pounce.

At one point her mark dribbles at her, rolls the ball with his sole, scissors over it, takes a touch—and Alyssa strips it off him easily. She bursts forward, finds an outlet, gets the ball back, mishits a cross into the side-netting and gets back to defend.

Two minutes later, she again makes a hard tackle and wins the ball. But here she finishes, crushing a shot into the back of the net. The closest player shakes his head, mumbling “Nah” with a disbelieving smile.

“They are not just ‘on the team’—they are standouts,” says Gonzalez.

“They’re so strong, they body kids,” says another teammate, 16-year-old midfielder Steven Sorto—the one with the earrings. “And in games? They show out.”

Brad Smith/ISI Photos/Getty Images

Team captain Brody Quinzon, who also played with the sisters when they first joined as 8- and 9-year olds, explains what showing out in a game looks like: “You hear a player or a parent or a coach on the other team saying to whoever’s matched up against them, ‘Oh, you’ve got her, she can’t keep up.’ And every single time, the very first play, that guy gets shut down completely. I can’t remember the last time Alyssa or Gisele let anyone beat them at anything. They’re on top of everyone. They throw in a tackle [even if] they’re 6 feet tall—they just stuff ’em, lock ’em down.”

After Alyssa scored her first goal this season—blowing by a guy and flying the rest of the way down the field—she started to nonchalantly jog back to her side of the field, but the guys called her over to the corner flag. The younger team, Gisele’s team, was watching from the sideline, and they ran to the flag, too, everybody swarming Alyssa, jumping and shouting, arms around each others’ shoulders.

“It’s not just the girls adapting to the boys, it’s also the boys adapting to the girls,” says Walker. “It’s realizing that girls can compete, that it has nothing to do with sex but with sheer athleticism, game IQ, execution. All our boys are learning that—along with their parents. They get in the car at the end of practice and ask, Is she any good? And their kid is telling them, Yeah, she’s really, really good.”

Gonzalez has made a tradition of celebrating his player’s accomplishments in a huddle at the end of practice, sharing in one another’s happiness as they get offered scholarships or called up to pro teams. Lately, the sisters’ feats have dominated that huddle talk—Gisele starting as a defender at the U-17 World Cup in India, and Alyssa getting called up to the women’s national team, making her debut at 17 in a friendly against England in front of 76,893 fans at Wembley. They also became the first high school athletes to sign an NIL contract with Nike. “So Alyssa and Gisele get paid to wear Nike,” Gonzalez teases, “while you guys pay Nike.”

“Can you get us some gear?” the guys ask.

“I’m a medium! Size 10 shoes!”

And when Alyssa became the first player drafted straight out of high school to the NWSL, her TFA teammates whistled: “Damn! Alyssa’s the LeBron of soccer!”

On draft day, Jan. 12 at Nike’s L.A. Headquarters, Alyssa was surrounded by family: Gisele on one side, 10-year-old sister Zoe on the other; plus parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins, all holding up her new No. 21 jersey. After initially committing to play college soccer at Stanford, she had opted to go straight to the pros, with ACFC orchestrating a three-team trade to nab her with the top pick.“The first thing you see is the blazing speed,” Hucles, ACFC’s GM, says of Alyssa. “But then you also notice an intelligence beyond her years, with her movements, her runs. You can see she has the ability, and the belief.” Every environment is different—and every rookie takes a while to adjust—but Alyssa, who is accustomed to a high-pressure setting, is upleveling quickly. “Already she is making an impact,” says Hucles. Within five minutes of a preseason friendly against Mexico’s Club América, her unofficial professional debut, she scored a trademark fly-by-everyone beauty of a goal, the first in a 3–0 win. Whether or not Alyssa or Gisele actually becomes the Next LeBron, they’ve already changed the game, carving out a new path for the girls coming up behind them. They are no longer the only girls in MLS Next—a handful of others have popped up around the country.

Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

Call it the Thompson Effect: With the growing buzz around the sisters, Walker says his traditionally male club has been “bombarded with interest from girls.” Gonzalez estimates that around 20 have tried out so far, and currently four of them are set to play next season with the boys, across multiple age groups. In fact, TFA will no longer have a “boys academy.” Now, it is just “the academy.”

Then there’s Eva Rojas. At 7, she’s playing up an age group with the 2014 TFA team, which won the prestigious Surf Cup, one of the nation’s top youth soccer tournaments, in Aug. 2022. On that January practice night in Pico Rivera, she arrived 30 minutes early, barreled out of a car, long-hair flying behind her, and dribbled by herself, at speed, in the dark, back and forth and around a lone tree. When a teammate eventually showed up, the two darted off to the field together, jabbering happily.

And while the Thompson sisters are quiet, all night long you could hear Eva’s shouts carrying across the field: “Pass the ball! Be my partner! Gooooal!” She is ebullient, nonstop.

By 9:30 p.m., the fields had cleared out. The coyote was back, standing under a streetlight. Eva was in the parking lot, still smiling, still abuzz. She watches the NWSL and La Liga MX Femenil, the Mexican women’s pro league, and she knows how much everything is changing. She’s an Angel City season ticket holder, and she’s got a new favorite player: her friend, Alyssa Thompson.

Gwendolyn Oxenham’s latest book, Pride of a Nation, is a commemorative history of the U.S. national team. She recently launched the 7-part audio docuseries Hustle Rule, hosted by Ted Lasso’s Hannah Waddingham, which is based on her book Under the Lights and in the Dark: Untold Stories of Women's Soccer. Check out a trailer here. She also made Pelada, a documentary about pickup games around the world.